Who makes the diagnosis

Conducting an extensive examination and formulating a final diagnosis is the responsibility of oncologists. Doctors have special training, which allows them to quickly and accurately diagnose most types of malignant tumors. However, therapists and specialized specialists play an equally important role: there are a number of suspicious symptoms that need to be looked for when examining patients with various complaints. This approach is called cancer vigilance.

Diagnosis methodology

Diagnostic errors are the most common type of medical errors. In most cases, their occurrence does not depend on a lack of knowledge, but on the inability to use it. A chaotic diagnostic search, even using the most modern special methods, is unproductive. In the practice of a surgeon, the correct technique for examining a patient is very important. The entire diagnostic process can be divided into several stages:

- symptom assessment;

- making a preliminary diagnosis;

- differential diagnosis;

- making a clinical diagnosis.

Stage I. _ Symptom assessment

The symptoms revealed during examination of the patient have different diagnostic value. Therefore, when assessing the results of the survey and physical examination data, the doctor, first of all, must select the most objective and specific ones from the many signs of the disease. Complaints such as deterioration in health, malaise, and decreased ability to work occur in most diseases, occur even with simple fatigue and do not help in making a diagnosis. On the contrary, weight loss, vomiting the color of “coffee grounds”, cramping abdominal pain, increased peristalsis, “splashing noise”, symptoms of peritoneal irritation, “intermittent claudication” are more specific symptoms; they are characteristic of a limited number of diseases, which makes diagnosis easier.

Isolating one main symptom can push the doctor to make hasty decisions. To avoid this trap, the doctor must consider as many symptoms as possible before starting to compose their pathogenetic combinations. Most doctors - consciously or not - try to reduce the available data to one of the clinical syndromes. A syndrome is a group of symptoms united anatomically, physiologically or biochemically. It covers signs of damage to an organ or organ system. The clinical syndrome does not indicate the exact cause of the disease, but it allows one to significantly narrow the range of suspected pathology. For example, weakness, dizziness, pallor of the skin, tachycardia and decreased blood pressure are characteristic of acute blood loss syndrome and are caused by a common pathophysiological mechanism - a decrease in blood volume and oxygen capacity of the blood.

Having imagined the mechanism of disease development, you can move on to the next stage of the search - by organs with which symptoms and syndromes are associated. The diagnostic search is also facilitated by determining the localization of the pathological process by local specific symptoms. This makes it possible to determine the affected organ or system, which significantly limits the number of disease options considered. For example, “coffee-ground-colored” vomit or black stools directly indicate bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract.

If it is impossible to isolate a clinical syndrome, the signs should be grouped into a specific symptom complex characteristic of damage to a particular organ or system. To determine a syndrome or identify a diagnostic symptom complex, it is not necessary to analyze all the patient’s symptoms, but the minimum number necessary to substantiate the diagnostic hypothesis is sufficient.

Sometimes characteristic manifestations of the disease cannot be detected at all. Then, due to circumstances, to make a preliminary diagnosis and carry out differential diagnosis, it is necessary to take nonspecific symptoms as a basis. In such cases, it is useful to weigh which of them can serve as the basis for a preliminary diagnosis and differential diagnosis. If the main complaint is weakness, it is useful to focus on the accompanying pallor of the skin and darkening of the stool. If the main complaint is nausea, then to judge the nature of the disease one should take the accompanying bloating and stool retention. At the same time, it is appropriate to recall the well-known postulate: “identified symptoms should not be added up, but weighed.”

The sequence of the diagnostic process in the classical version can be seen in the following clinical example.

A 52-year-old patient came to you about attacks of pain “in the right side” that have been bothering her for the last two months. Typically, an attack occurs after errors in the diet, especially after eating fatty foods, and is accompanied by nausea and bloating. Outside of exacerbation, heaviness in the right hypochondrium and a feeling of bitterness in the mouth persist. Recently, my health has worsened and my performance has decreased. The results of physical examination are within normal limits.

This patient's main complaint is pain in the epigastric region and right hypochondrium. She sought help because the pain was recurring and had become more intense. Thus, isolating attacks of pain as the leading symptom allows the doctor to concentrate on the important manifestation of the disease that most worries the patient and forces her to seek medical help.

This patient has a very definite clinical picture. In such cases, doctors act in an unusually similar way (the doctor’s reasoning and his further diagnostic efforts will be presented below).

Stage II . Making a preliminary diagnosis

A preliminary judgment about the nature of the disease is the next stage of the diagnostic process. Suspicion of a particular disease arises naturally when comparing its textbook descriptions with the existing symptoms. In the process of such a comparative analysis, the doctor has guesses, depending on the degree to which the symptoms correspond to the description of the disease that he remembers. Often such a comparison allows one to quickly formulate a preliminary diagnosis.

Typically, doctors, guided more by intuition than by logic, instantly compare the identified complaints and symptoms with the clinical manifestations of certain diseases imprinted in their memory, and assume the presence of a particular disease. Already during the collection of data, switching attention from one symptom to another or highlighting a clinical syndrome, the doctor does not just collect information - he already formulates his first assumptions about the existing pathology. The process of making a preliminary diagnosis provides an opportunity to turn the question “what could cause these complaints?” to another question, which is easier to answer: “is there disease N here?” This strategy is much more rational than trying to make a diagnosis by summarizing all conceivable information.

In the case of our patient, the localization of the pain and its connection with the intake of fatty foods will make most doctors immediately suspect cholelithiasis (GSD). With this disease, pain is usually localized in the right hypochondrium and occurs after eating fatty foods. Thus, the symptoms in our patient fully correspond to the textbook picture of cholelithiasis. Now the doctor faces another question: does the patient really have this disease?

The diagnosis, based on history and physical examination, is rarely certain. Therefore, it is better to talk about the likelihood of a particular preliminary diagnosis. As a rule, doctors use expressions like “most likely” or “maybe”. The diagnostic hypothesis, no matter how fully it explains the development of the patient’s complaints, remains a conjectural construct until diagnostic, usually laboratory-instrumental, signs of the disease are identified.

Stage III . Differential diagnosis

In the course of differential diagnosis, we are faced with a different task than when making a preliminary diagnosis. In formulating a preliminary diagnosis, we sought to identify one possible disease. When conducting differential diagnosis, on the contrary, it is necessary to consider all diseases that are somewhat probable in a given situation and select the most similar ones for active testing. Having formulated a preliminary diagnosis, the doctor often realizes that he is faced with a whole set of alternative versions. When using computer diagnostic systems, you can be amazed at the sheer number of options that appear on the display screen. The number of diagnostic versions increases even more if you look at the list of diseases responsible for a particular symptom. It takes remarkable judgment to select from an extensive list of possible diseases those conditions that may apply to a particular case.

Faced with a long list of possible diagnoses, we must first narrow them down to the most likely ones. Physicians, like most other people, can usually actively consider no more than five versions at a time. If the clinical picture corresponds to a specific syndrome, the differential diagnosis is greatly simplified, since only a few diseases that include this syndrome remain to be considered. In cases where it is not possible to determine the syndrome or the affected organ, diagnosis becomes more complicated due to the large number of possible diseases. Limiting the number of most likely versions helps the doctor decide which additional tests to choose to confirm or rule out a suspected pathology. This algorithm of the surgeon’s actions allows, with the least loss of time and the greatest safety for the patient, to make an accurate diagnosis and begin treatment of the patient.

The alternative versions are tested one by one, comparing each with the preliminary diagnosis and discarding the less likely of each pair of diseases, until the one that best fits the collected data is selected. Of the competing hypotheses, the most probable is the one that most fully explains the presence of a complex of manifestations of the disease. On the other hand, the doctor may have two hypotheses, the symptomatology of each of which can explain the presence of the entire set of identified symptoms in the patient, but in relation to one of them the doctor knows a fairly extensive list of almost obligatory specific symptoms that were not found in this patient. In such a situation, it is advisable to consider this particular diagnostic hypothesis less probable.

Investigating alternative versions one after another, the doctor relies on the so-called hypothesis testing technique. This heuristic is based on the fact that the test results serve to confirm the diagnosis if they are positive, or to exclude it if they are negative. Ideally, positive results allow us to definitively establish the disease, and negative results allow us to unconditionally exclude it.

The choice of diseases subject to differential diagnosis should take into account the following main points:

- similarity of clinical manifestations;

- epidemiology of the disease;

- "severity" of the disease;

- the danger of the disease to the patient’s life;

- the severity of the patient’s general condition and his age.

When including a particular disease in the list requiring differential diagnosis, it is important to take into account the frequency of its observation among a given population of people. The most common diseases should be taken into account first. An old medical rule says: “Frequent diseases are common, rare diseases are rare.” This is true even when widespread diseases present with unusual symptoms. A methodological error known as ignoring the background level is that doctors tend to rely primarily on the coincidence of symptoms with the known clinical picture, without taking into account epidemiological data. GSD and acute appendicitis, for example, are so widespread that they should be suspected even if there is atypical abdominal pain. Myocardial infarction should not be forgotten in any case of pain “from the nose to the navel.”

The initial probability of illness is most easily taken into account if you immediately ask yourself the question, does the patient have a suitable lifestyle or personality type? It is not enough to know that acute pancreatitis is a common disease; It is important to consider that it is especially common in people who abuse alcohol. When dealing with such patients, one must always be wary of this disease, even if the symptoms do not fully correspond to them. The age of the patient can provide some assistance in establishing the range of diseases requiring differential diagnosis. Elderly patients are much more likely to have vascular and cancer diseases, while acute appendicitis is more common in young and middle-aged people.

Excluding unlikely but serious diseases from initial consideration is likely necessary but also dangerous. The doctor should not forget about them. We have to return to these versions when, when considering common diseases, there is no certainty in the diagnosis. In such a situation, you need to think about the possibility of a rare disease.

When deciding which diseases to carry out differential diagnosis, the doctor must also take into account the “acuteness” of the disease and the severity of the patient’s condition. In addition, when considering a plan for examining a patient, you need to ask yourself which of the suspected diseases poses the greatest threat to the patient’s life.

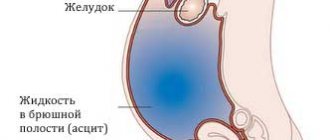

In our clinical example, cholelithiasis is very likely. The widespread prevalence of this disease plus the classic clinical picture speak in favor of this version. Meanwhile, despite the obvious validity of suspicions of cholelithiasis, the existence of other possible diseases cannot be immediately rejected. First of all, gastritis, peptic ulcers and chronic pancreatitis should be excluded. Another possibility is stomach or pancreatic cancer. Another less likely possibility is colon cancer. And the likelihood of chronic appendicitis is very low. Therefore, in this patient, colon cancer and chronic appendicitis can, at least temporarily, be excluded from the list of actively being studied versions. This conclusion is based on the fact that, on the one hand, their manifestations do not have a clear connection with errors in the diet; on the other hand, these diseases usually manifest themselves with other symptoms.

Usually, after making a preliminary diagnosis and compiling a list of diagnostic options that require verification, the doctor prescribes an additional examination. In this case, there is often a temptation to resort to the extended use of instrumental methods. Meanwhile, when prescribing this or that diagnostic test, the doctor must be aware of: “why was this particular test chosen and why is it needed?” Laboratory or instrumental research may be necessary, first of all, to confirm or exclude a specific disease.

If several different methods can be used to diagnose a particular disease, you should choose the most informative, accessible and safe one possible. When multiple diagnostic tests are used, it is natural to assume that the accuracy of the diagnosis is higher. In such a case, we rely on the sum of the evidence. This only makes sense if the tests ordered provide independent evidence. To achieve this, it is necessary to study phenomena that are different in nature. For example, both gastroscopy and x-ray examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract are aimed at searching for changes in the stomach. The total result of both tests is not much more significant than the result of one of them. Likewise, the use of abdominal ultrasound and CT to detect pancreatic tumors adds little to the findings of CT alone. On the other hand, gastroscopy, which reflects the condition of the stomach, and ultrasound, which allows us to judge the presence of changes in other organs of the abdominal cavity, provide independent information, summarizing which we increase the validity of diagnostic conclusions. In this approach, the doctor performs or orders diagnostic tests not to cover all possible diseases, but only to differentiate one disease from another.

Stage IV . Making a clinical diagnosis

After making a preliminary diagnosis and checking alternative versions, the doctor chooses one disease. If the results of instrumental studies confirm the chosen variant of the disease, this indicates its correctness with a high degree of probability. If, at the same time, the results of tests prescribed to exclude alternative diagnoses actually reject them, then this result can be completely relied upon.

The sequence of techniques in the traditional approach to diagnosis can be presented as the following diagram:

Manifestations of the disease → Main symptoms → Clinical syndrome → Affected organ → Cause of the syndrome → Differential analysis of individual diseases → Clinical diagnosis.

As knowledge and experience accumulate, the doctor acquires the ability to quickly overcome all of the specified stages of the diagnostic process. He doesn't collect all the data first and then stop and think about it. On the contrary, he actively obtains information and processes it at the same time. After a short introductory period, during which the patient has time to express his complaints, an experienced doctor formulates a preliminary diagnosis, continues to collect anamnesis and methodically examine the patient, based on his impression.

Before making a clinical diagnosis, he can go through all the stages again, collecting additional data, checking the reliability of the information received, and figuring out how it all fits together. The diagnostic process in the consciousness (and subconscious) of the doctor goes on non-stop, meanwhile, an attempt to isolate the main thing at each stage can be useful not only for students, but also for experienced clinicians. Understanding the patterns of the diagnostic process allows the doctor to always act according to the system, logically moving from one stage to another.

To check the preliminary diagnosis of cholelithiasis in our clinical observation, it is advisable to perform an ultrasound, which, in the presence of stones in the gallbladder, almost always reveals them. To exclude gastritis, peptic ulcer or stomach cancer in our patient, it is best to use gastroscopy, which is highly specific for these diseases. The use of these additional studies, confirming cholelithiasis and excluding other diseases, allows you to quickly and confidently make a final clinical diagnosis - cholelithiasis. If there were no signs of damage to the gallbladder, stomach, duodenum and pancreas, there would be a need to examine the large intestine by colonoscopy or irrigoscopy.

The proposed approach to making a clinical diagnosis, in fact, is a set of heuristic rules that obviously simplify reality, but which provides a logical diagram of the diagnostic process. Of course, it is not free from drawbacks, and a number of other techniques are needed to achieve success in difficult clinical situations.

Preparation of medical documentation

Many doctors strive to describe the disease in medical documentation as the patient describes it, believing that this style is most consistent with reality, and therefore most adequately reflects the nature of the disease. However, a patient’s description of a disease is just his subjective point of view and therefore, as a rule, is very rarely comparable to modern medical views. A correct idea of a disease that corresponds to scientific views can only be formed by a doctor based on a comparison of information obtained in a conversation with the patient and during an examination, on the one hand, and, on the other, medical knowledge about the manifestation of diseases. It is the doctor’s point of view on the disease that should be presented in medical documents.

Before starting to write a “Medical History”, it is necessary to determine the main disease, its complications and concomitant diseases, since the verbal a posteriori model is built by the doctor as if from the end, from the formulation of the diagnostic concept, and only by constantly keeping it in mind can it be competently, highly professionally drawn up medical documentation. The absence of a unifying final goal of presenting a “case history,” i.e., substantiation of the formulated final or prospective diagnosis, leads to a chaotic, unsystematized description of the facts obtained as a result of interviewing the patient. From here it is also obvious that a well-thought-out medical history cannot be written directly from the patient’s words “at the bedside”. Such a description will reflect mainly the course of the conversation between the doctor and the patient, and not the doctor’s understanding of the essence of the pathological process.

Writing a medical history according to the rule “what is heard is how it is written” deprives the doctor of the opportunity to regularly evaluate symptoms according to the degree of specificity and form a diagnostic hypothesis. However, this does not mean that the doctor should not take any notes during a conversation with the patient; on the contrary, the interview protocol greatly facilitates the writing of a medical history, freeing the doctor from the need to memorize private information - dates, list of medications, etc. Medical documentation must be presented in such a way that each section substantiates the attending physician’s own diagnostic and treatment concept, and any other doctor or expert, having read it, can understand on what basis the diagnosis was formulated and the treatment method was chosen.

* * * * *

A doctor can arrive at the same diagnosis in different ways, but the one who carefully selects the starting points in the diagnosis works more efficiently and quickly. The path to an accurate clinical diagnosis should be as short as possible, with the primary use of non-invasive and low-cost diagnostic methods. However, it is not at all necessary to use all available research methods. The scope of research methods should be minimally sufficient to make an accurate diagnosis and clarify the characteristics of the course of all concomitant diseases that can affect the choice of method and treatment tactics. This requires clear, logical and consistent actions with targeted use of available instrumental and laboratory diagnostic methods.

In complex clinical cases, the diagnostic process is based not only on general logical principles using modern technological advances, but also on the intuitive elements of surgical thinking and often remains exclusively the domain of the intellect and hands of the surgeon. Good knowledge of clinical medicine and extensive practical experience allow the doctor to successfully use the “sixth sense” in these situations.

Mandatory questions for patients that the doctor should

ask when taking anamnesis. Table 2. 1.

| Does the patient suffer from: ¨ coronary heart disease and whether you have had a myocardial infarction ¨ cerebrovascular accident and whether you suffered acute cerebrovascular accident ¨ hypertension ¨ bronchial asthma ¨ diabetes mellitus ¨ liver and kidney diseases ¨ infectious diseases (HIV, hepatitis, syphilis, tuberculosis) ¨ allergic reactions to medications |

Characteristics of diagnostic methods Table 2. 2.

| Index | Characteristic | The question this indicator answers | Formula for calculation |

| Sensitivity | The probability of a positive result in the presence of the disease. | How good is the test at identifying people with the disease? | A ____ A+C |

| Specificity | Probability of a negative result in the absence of disease | How good is the test at excluding people who do not have the disease? | D _____ B + D |

| Positive predictive value | There is a possibility that if the test is positive, the disease actually exists. | What is the likelihood of having this disease? | A ______ A + B |

| Negative predictive value | The likelihood is that with a negative test there really is no disease. | What is the probability of not having this disease? | D _______ S + D |

| Diagnostic accuracy | Probability of correct diagnosis | What is the diagnostic accuracy of the method? | A+D ___________ A + B + C + D |

where: A – true positive results of the method,

B – false positive results of the method,

C – false negative results of the method,

D – true negative results of the method.

Stages of cancer diagnosis

1. Examination by a doctor. First, the doctor carefully listens to complaints and collects anamnesis, after which he conducts an external examination to identify signs of skin cancer and other superficial tumors.

2. Standard laboratory tests. The patient is prescribed blood, urine and stool tests, and a study for basic tumor markers.

3. Instrumental visualization. Depending on the complaints and the presumed location of the cancerous tumor, ultrasound, radiography, CT or MRI, and endoscopic examination methods are performed.

4. Histological confirmation. The most accurate method for diagnosing cancer is a biopsy of tumor tissue followed by studying the biomaterial under a microscope. This allows the doctor to confirm the presence of cancer pathology and determine its type.

5. Additional methods. In some cases, oncogenetic and immunohistochemical tests are required, especially if modern targeted therapy is planned.

Diagnostics

CT, MRI studies

The Department of Computed and Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Center conducts a wide range of highly informative studies, both to diagnose all pathologies of the heart and blood vessels, and to determine concomitant diseases of other organ systems.

The department has extensive experience, the accuracy of the diagnoses is confirmed by data obtained during operations, which confirms the high qualifications of our radiology doctors, who have degrees of candidates and doctors of science, and 20 years of experience in CT and MR diagnostics of congenital and acquired defects, vascular anomalies , coronary disease, etc. The presence of the latest generation CT and MR tomographs and the latest computer data processing programs in the Center allows, without invasive procedures and hospitalization, to obtain a comprehensive, accurate diagnosis of the pathology of the coronary arteries, cerebral vessels, kidneys, lower extremities, aorta and pulmonary artery , diagnose heart and vascular defects. And also using MRI to evaluate the condition of the myocardium, heart function, blood flow in the heart and blood vessels, diagnose any cardiopathy, identify inflammation of the heart muscle (myocarditis) and scar in the myocardium after a heart attack. Cardiac surgery patients often require dynamic monitoring with CT and MRI to evaluate the results of the operation and determine further treatment tactics. The presence of stents, coronary artery and vascular shunts, conduits, artificial valves and prostheses is not a contraindication to performing MRI of any organ, including the heart. The department also performs CT and MR diagnostics of concomitant pathologies of the brain, chest organs (lungs, mediastinum), abdominal cavity, kidneys, and spine. CT and MR studies of the heart and blood vessels are carried out in adults and older children on an outpatient basis, in comfortable conditions, using modern expert-class equipment. If it is necessary to administer a contrast agent, it is injected into the cubital vein, painlessly and safely, using an injector syringe; before contrast studies, you must refrain from eating and drinking for at least 4 hours; After a contrast study, the patient is advised to drink plenty of fluids throughout the day.

For children under 5 years of age, including children in the first year of life, CT and MRI studies of the heart and blood vessels are performed while the child is in medicated sleep, under the supervision of an anesthesiologist; therefore, in such cases, hospitalization in a hospital for 2 days is necessary.

Contraindications to CT and MRI studies with contrast agents are allergic reactions to contrast agents and renal failure.

The studies are carried out by prior appointment of the patient (via a call center, website or by telephone at the CT and MRI Center department) and a referral from the attending doctor of the clinic, with a clear indication of the purpose and objectives of the study, in the absence of contraindications to the administration of contrast agents.

The research results are provided to the patient or his authorized representative in the form of a conclusion with a description, calculated data and images, in accordance with standardized protocols; If necessary and at the request of the patient, images can be obtained on electronic media, CD/DVD disks, the next day after the examination.

Detailed information and registration for research can be obtained by calling the department, 414-79-01

PET CT

Screening for cancer

In order not to miss cancer pathology at an early stage, when there are no symptoms yet, all people are recommended to undergo annual preventive examinations - health check-ups. This is especially important for patients after 40-45 years of age, as well as for those who have blood relatives diagnosed with cancer.

Cancer screening programs may include the following types of tests:

● OneTest is the “gold standard” for early cancer diagnosis, which shows the current risk of developing cancer

● preventive colposcopy at 40 years of age, and then 8-10 years later, if there were no pathological changes during the first examination

● for women - colposcopy and cytological Papanicolaou smear (PAP test), examination by a mammologist with mammography or ultrasound of the mammary glands

● for men - test for prostate-specific antigen, digital examination of the prostate

Early diagnosis of diseases: why it is important and why it is needed

Detection of a disease before its initial signs appear is a chance to avoid it altogether, as well as eliminate the risk of developing parallel ailments that have a devastating effect on a person’s performance, psyche, and quality of life. Early diagnosis makes it possible to timely identify and block various dangerous diseases, in particular cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Treating such diseases at an early stage can save lives and significantly save money on their treatment. What is early diagnosis? This is a comprehensive program of tests and research, which a specialist selects individually for each patient depending on his age, gender, and nature of complaints. Early diagnostic methods are studies of various organs in order to determine possible pathologies. The purpose of the method is to: • make the correct diagnosis; • determine the location of the pathology and its level of severity; • check hormone balance; • find out whether there is a lack of vitamins necessary for the body. Who is recommended for regular preventive diagnostics: • People who are overweight, have bad habits, have weak immunity; • Elderly persons; • Persons with chronic diseases; • Workers of hazardous industries; • Citizens living in environmentally unfavorable conditions; • Persons with a hereditary predisposition to certain diseases. A special risk group is people over 40 years of age. Starting from this time, regular examinations for the presence of the beginnings of oncological processes are recommended. For women, this measure is aimed at timely detection of breast cancer, and for men, prostate or testicular cancer. Statistics show that cancer can be successfully cured if it is detected early. Consultations with a mammologist, mammography and ultrasound of the mammary glands can protect against the development of a dangerous disease. Also, all women, regardless of age, must periodically undergo cytological examination. Men are advised to visit a urologist and undergo blood tests for male diseases. In addition, all people, regardless of gender, are not required to be tested for sexually transmitted infections. Married couples who are planning to have a child are recommended to undergo a series of examinations to determine the possible risks of developing pathologies in the fetus and take measures to avoid them. The M-Vita medical center near the Khovrino and Rechnoy Vokzal metro stations offers a wide range of services related to the early diagnosis of various diseases. Patients can choose a convenient time for examinations. At the same time, the time spent on procedures will not harm professional activities. The main goal is to keep your health under control and gain confidence in the future. In the laboratory of the M-Vita clinic, you can undergo tests of varying degrees of complexity, and if problems are identified, the medical center’s specialists are ready to provide competent medical care.

Unification of requirements for formulating a diagnosis

To implement this WHO recommendation, local (national) rules for analyzing morbidity and mortality for multiple causes were developed. In 1971 G.G. Avtandilov, in order to take into account and analyze morbidity and mortality for multiple causes, proposed the concept of “combined underlying disease” based on the identification of mono-, bi- and multicausal types of diagnoses. A combined underlying disease, represented by either two competing, or combined, or primary and background diseases, has found wide application. Rules were developed for identifying the nosological unit, which is placed in first place in the combined underlying disease, as the main unit of accounting in the statistical analysis of morbidity and the initial cause of death in case of death. However, as rightly stated in the recommendations of the Ministry of Health of Russia, the replacement of the heading “Main disease” with the concept of “combined main disease” in the case of comorbidity currently violates the requirements of the current federal legislation and ICD-10, and in case of deaths, it unnecessarily complicates the choice of the so-called initial cause of death - basic statistics of causes of death in the population.

The basis for improving the rules for formulating a diagnosis and, in case of death, issuing a medical death certificate should be based on modern definitions and requirements of the current legislation of the Russian Federation (Federal Law No. 323-FZ) and WHO experts, reflected in ICD-10.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis (Greek διάγνωσις - recognition) is a medical report on the state of health, on an existing disease (injury, condition), expressed in terms provided for by the accepted classifications and nomenclature of diseases, denoting the name of diseases (conditions), their forms, variants of the course and based on comprehensive systematic study of the patient. The content of the diagnosis can also be special physiological conditions of the body (pregnancy, menopause, the state after resolution of the pathological process, etc.), a conclusion about the epidemic focus.

Disease

The disease is defined as a violation of the body's activity, performance, and ability to adapt to changing conditions of the external and internal environment, arising in connection with the influence of pathogenic factors with simultaneous changes in the protective-compensatory and protective-adaptive reactions and mechanisms of the body.

The condition is defined as changes in the body that occur due to exposure to pathogenic and (or) physiological factors and require medical care. The leading principle of formulating a diagnosis in medicine is nosological.

Here are some terms and definitions in accordance with the industry standard OST TO No. 91500.01.0005-2001 [10]:

1) nosological form (unit) is defined as a set of clinical, laboratory and instrumental diagnostic signs that make it possible to identify a disease (poisoning, injury, physiological state) and classify it as a group of conditions with a common etiology and pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, general approaches to treatment and correction conditions;

2) a syndrome is a condition that develops as a result of a disease and is determined by a set of clinical, laboratory, instrumental diagnostic signs that allow it to be identified and classified as a group of conditions with different etiologies, but a common pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, general approaches to treatment, which at the same time depend on from the diseases underlying the syndrome.

A diagnosis is an integral expression of a medical specialist’s understanding of the patient’s health status and the existing disease (injury, condition) based on data obtained as a result of diagnostics, which is a complex of medical interventions aimed at recognizing conditions or establishing the presence or absence of diseases carried out through collecting and analyzing patient complaints, medical history and examination data, conducting laboratory, instrumental, pathological and other studies in order to determine the diagnosis, select measures for treating the patient and (or) control the implementation of these measures.

Based on the above provisions of federal legislation, the diagnosis is endowed with various functions:

1) medical: diagnosis is the basis for the choice of treatment methods and preventive measures, and also serves to assess the prognosis of the development of the disease;

2) social: the diagnosis is the basis for a medical examination (examination of temporary disability, medical social examination, military medical examination, forensic medical and forensic psychiatric examination, examination of professional suitability and examination of the relationship of the disease with the profession, as well as examination of the quality of medical care) ;

3) economic: diagnosis is the basis for regulatory regulation of healthcare within the framework of procedures for the provision of medical care, standards of medical care and clinical recommendations (treatment protocols).

4) statistical: diagnosis is a source of state statistics on morbidity and causes of death of the population. Taking into account the legally established priority of the patient’s interests in the provision of medical care, not a single function of the diagnosis can be implemented by creating conditions that could lead to a decrease in the quality of medical care. And therefore, the diagnosis should always be a complete, as far as possible in specific conditions, medical report on the state of health and the existing disease (condition).

The medical and social functions of diagnosis take priority over the economic and statistical ones. In this regard, we emphasize that any dilution or simplification of the diagnosis, motivated by the need to fit it into standardized formulations, schemes or rules, is unacceptable.

Russian healthcare has traditionally adopted a general diagnosis structure that strictly meets WHO requirements and includes the following components, or headings:

1. underlying disease - a disease that, by itself or in connection with complications, causes a primary need for medical care due to the greatest threat to performance, life and health, or leads to disability or causes death;

2. concomitant disease - a disease that does not have a cause-and-effect relationship with the main disease, is inferior to it in the degree of need for medical care, influence on performance, danger to life and health, and is not the cause of death.

It should be noted that the concepts of “main disease” and “concomitant disease” are defined by law and are not subject to modification in further discussion of these terms. From the legally established definition of the underlying disease, it follows that the structure of the diagnosis must include the heading “Complications of the underlying disease,” which determine the priority need for medical care in connection with the greatest threat to performance, life and health, either leading to disability or causing death.

Based on this provision, the general structure of the diagnosis should be represented by the following headings:

1. Main disease.

2. Complications of the underlying disease.

3. Concomitant diseases.

This classification of diagnosis was first approved by order of the USSR Ministry of Health dated January 3, 1952 No. 4 and has been preserved unchanged to this day in medical record forms.

But even with this simplest diagnosis design, difficulties may arise when choosing the main and concomitant diseases (conditions), so WHO experts have adopted a number of rules for selecting diseases (conditions) that are used in the analysis of morbidity and mortality.

Thus, it is recommended that the condition that should be used for single-cause morbidity analysis be the one for which treatment or testing was performed during the relevant health care episode. In this case, the main condition is defined as a condition (disease, injury) diagnosed at the end of an episode of medical care, for which the patient was mainly examined and treated. If there is more than one such condition (disease), the one that accounts for the largest portion of the resources used is chosen as the main one.

To analyze the causes of death, WHO experts introduced the concept of “initial cause of death,” which is defined as a disease (injury) that caused a chain of disease processes that directly led to death, or the circumstances of an accident or act of violence that caused a fatal injury.

A fatal complication that determines the development of the terminal condition and the mechanism of death (but not an element of the mechanism of death itself) is defined as the direct cause of death.

Thus, the concept of the initial cause of death is similar to the concept of the underlying disease, and the concept of the immediate cause of death is similar to the fatal complication of the underlying disease. Concomitant diseases, since they do not contribute to death and do not have a cause-and-effect relationship with the underlying disease, cannot be associated with the cause of death, are not used in the statistics of causes of death and therefore are not included in the medical death certificate.

ICD-10 defines comorbid diseases (conditions) as other important diseases (conditions) that contributed to death. In the diagnosis design, it is advisable to indicate such comorbid diseases (conditions) as competing, combined and/or background diseases (conditions) in an additional heading after the “Main disease” heading. They must have common complications with the underlying disease, since they jointly cause a chain of disease processes that directly lead to death.

Based on these provisions, the structure of the diagnosis for comorbidity should be represented by the following headings:

1. Main disease.

2. Competing, combined, background diseases (comorbid diseases, if any).

3. Complications of the main (and comorbid, if any) diseases.

4. Concomitant diseases.

Competing disease

It is defined as a nosological unit (disease or injury) that the deceased suffered from simultaneously with the underlying disease, and each of them individually could undoubtedly lead to death.

Combined disease

It is defined as a nosological unit (disease or injury) that the deceased suffered from simultaneously with the main disease, and which, being in various pathogenetic relationships and aggravating each other, led to death, and each of them individually would not have caused death.

Background disease

It is defined as a nosological unit (disease or injury), which became one of the causes of the development of another independent disease (condition), aggravating its course and contributing to the occurrence of general fatal complications leading to death.

According to WHO rules, only one of these conditions, selected according to the ranking tables recommended by WHO, should be considered as the underlying cause of death. In the diagnosis, this disease (condition) is indicated under the heading “Main disease” and is included in part I of the medical death certificate. All other diseases (conditions) associated with the cause of death (competing, concomitant and background), in accordance with the recommendations for the need for analysis for multiple causes, should be reflected in Part II of the medical certificate of death as other important conditions contributing to death.

Thus, the structure of the diagnosis should include the following sections: the main disease, complications of the main disease and concomitant diseases. The heading “Main disease” indicates only the disease (condition) that became the reason for carrying out therapeutic and diagnostic measures during the last episode of medical care, and in case of death, by itself or through its complications could lead to death. This disease (condition) is indicated and coded in Part I of the medical death certificate as the underlying cause of death.

In the corresponding paragraphs of Part I of the death certificate, the immediate cause of death (fatal complication) and the so-called intermediate conditions are recorded, which are selected from the section “Complications of the underlying disease”, but are not coded. In case of comorbidity, other important diseases (conditions) that became the reason for the provision of medical care, and in case of death, contributed to death, defined as competing, combined and/or background diseases, are indicated in the diagnosis in an additional heading after the heading “Main disease” and are entered accordingly , in part II of the medical death certificate with the corresponding ICD-10 codes.

Concomitant diseases (conditions) are not included on the medical death certificate and are not coded as having no cause-and-effect relationship with the underlying disease, and in the event of death, not influencing the occurrence of death.

Information about authors:

Zairatyants Oleg Vadimovich – Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of Pathological Anatomy, Moscow State Medical and Dental University. A.I. Evdokimov" of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Vice-President of the Russian and Chairman of the Moscow Society of Pathologists

Malkov Pavel Georgievich - Doctor of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor, Professor of the Department of Pathological Anatomy of the Russian Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education of the Ministry of Health of Russia, head of the pathological anatomy course of the Department of Physiology and General Pathology of the Faculty of Fundamental Medicine of the Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education "Moscow State University" them. M.V. Lomonosov"

Lev Vladimirovich Kaktursky – Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Scientific Director of the Federal State Budgetary Institution “Research Institute of Human Morphology”, President of the Russian Society of Pathologists (Moscow)

Share on social media networks