Rational antibacterial therapy for acute upper respiratory tract infection (rhinosinusitis)

Upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) include damage to the mucous membrane of the respiratory tract from the nasal cavity to the tracheobronchial tree, with the exception of the terminal bronchioles and alveoli. Due to the fact that most URTIs are initially viral in nature, the potential for using antibacterial drugs (AP) is limited. Each case of prescribing an AP should be considered individually. This approach involves identifying cases of disease in which the effect of antibacterial therapy (AT) prevails over its adverse consequences.

Acute sinusitis is a common complication of acute respiratory viral infection (ARVI). Examination of patients with symptoms of acute respiratory illness lasting > 48 hours showed the presence of radiological signs of sinusitis in 87% of cases. The invariably concomitant rhinitis makes the use of the term “rhinosinusitis” preferable. ARVI is complicated by bacterial rhinosinusitis in 0.5–2% of cases in adults and in 5–10% of cases in children. In Russia, according to estimates, about 10 million people suffer from acute rhinosinusitis annually, while in the USA - about 31 million.

Diagnostics

Most patients with acute rhinosinusitis are treated on an outpatient basis (the exception is cases of inflammation of the sphenoidal sinuses, since thrombosis of the cavernous sinuses is possible). A distinctive diagnostic feature of bacterial rhinosinusitis from ARVI, accompanied by exudation in the sinuses, is the duration of symptoms > 10 days (but < 12 weeks) or a two-phase course with deterioration after 5 or more days, the presence of purulent secretion and pain, especially monolateral, aggravated by local percussion , as well as clinical deterioration after a short period of symptomatic relief (bacterial rhinosinusitis is observed in approximately 20% of patients with a duration of symptoms of less than 1 week; at the same time, 70% of people who seek medical help for sinusitis symptoms that persist for more than 1 week have no radiological signs of bacterial inflammation). Taking into account these, as well as the signs indicated below, a significant number of cases of viral etiology are excluded.

The diagnostic significance of signs of rhinosinusitis was studied in a study by J. Williams and M. Lindbaek table. The latter identified four symptoms that predict the disease with a high degree of certainty. These included: biphasic course of the disease, purulent rhinorrhea, purulent contents in the nasal cavity and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) > 10 mm/h. When three of the four symptoms were present, the test specificity was 81% with a sensitivity of 66%. At the same time, for such a sign as perimaxillary edema, the specificity is 99%. Most other symptoms detected during examination are characterized by low prognostic value.

Diagnosis of rhinosinusitis is based primarily on clinical, anamnestic and laboratory data. At the same time, the frequent detection of radiological signs of rhinosinusitis in acute respiratory viral infections limits the capabilities of radiological research methods. That is why radiography is excluded from the list of routine methods for diagnosing uncomplicated forms of rhinosinusitis. The use of radiation research methods in the overwhelming majority is inappropriate due to the unreasonable increase in the cost of treatment.

Classification

According to the methodological recommendations approved by the Commission on Antibiotic Policy under the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation and the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, the Interregional Association for Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, a classification has been adopted that distinguishes:

- Acute sinusitis (< 3 months).

- Recurrent acute sinusitis (2–4 cases of acute sinusitis per year).

- Chronic sinusitis (> 3 months).

- Exacerbation of chronic sinusitis (intensification of existing and/or appearance of new symptoms).

In order to optimize treatment tactics, it is also possible to distinguish the following forms of rhinosinusitis:

- By place of development: A.1. Out-of-hospital. A.2. Nosocomial.

- According to the duration of symptoms: B.1. Acute (duration < 4 weeks). B.2. Subacute (4–12 weeks). B.3. Chronic (> 12 weeks, or ≥ 4 cases of acute recurrent rhinosinusitis lasting > 7–10 days, provided that residual effects persist in the sinus 4 weeks after the end of therapy).

- According to premorbid background: C.1. Rhinosinusitis in persons with normal immune status. C.2. Rhinosinusitis in immunosuppressed individuals. C.2.1. Humoral immunodeficiency. C.2.2. Cellular immunodeficiency.

The above comments on classification have been presented in consensus recommendations of the American Academy of Otolaryngology, the Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, and several other societies. Sinusitis is divided into four categories: acute (bacterial) rhinosinusitis, chronic rhinosinusitis without polyps, chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps, and allergic fungal sinusitis. According to foreign experts, the updated classification allows for more targeted treatment of the disease, however, a discussion of its advantages is beyond the scope of this article.

The tactics of AT rhinosinusitis, like other respiratory tract infections, depend on the severity of the disease and complications. The severity is assessed by the totality of symptoms. For example, if orbital or intracranial complications are suspected, the course is always regarded as severe, regardless of the severity of other symptoms.

According to the severity of the flow, they are distinguished:

- mild course - nasal congestion, mucous or mucopurulent discharge from the nose and/or into the oropharynx, increased body temperature up to 37.5 ° C, headache, weakness, hyposmia; on an x-ray of the paranasal sinuses - the thickness of the mucous membrane is less than 6 mm;

- moderate - nasal congestion, purulent discharge from the nose and/or into the oropharynx, body temperature above 37.5 ° C, pain and tenderness on palpation in the projection of the sinus, headache, hyposmia, malaise, there may be radiating pain in the teeth and ears; on an x-ray of the paranasal sinuses - thickening of the mucous membrane more than 6 mm, complete darkening or fluid level in one or two sinuses;

- severe - congestion, often profuse purulent discharge from the nose and/or into the oropharynx (but there may be a complete absence of them), body temperature above 38 ° C, severe pain on palpation in the projection of the sinus, headache, anosmia, severe weakness; on the x-ray of the paranasal sinuses - complete darkening or fluid level in more than two sinuses; blood test: leukocytosis, shift of the leukocyte formula to the left, increase in ESR; orbital, intracranial complications or suspicion of them. An extremely serious complication is cavernous sinus thrombosis, the mortality rate of which reaches 30% and does not depend on the adequacy of antibacterial therapy.

The standard for the etiological diagnosis of rhinosinusitis is a bacteriological examination of the aspirate obtained during sinus puncture. The diagnostically significant titer is 105 CFU/ml. The pathogen can be isolated in 60% of cases; According to some data, in 20–30% of cases, polymicrobial etiology is determined. The latter is more typical for the subacute and chronic course of the disease.

There is a close dependence of the role of pathogens on the course of the disease: in acute rhinosinusitis and exacerbation of chronic rhinosinusitis, Streptococcus (Str.) pneumoniae (20–35%) and aemophilus (H.) influenzae (nontypeable strains, 6–26%) are of primary importance. More severe cases of the disease are more often associated with Str. pneumoniae Much less common causes of rhinosinusitis are Moraxella (M.) catarrhalis (and other gram-negative bacilli, 0–24%), Str. pyogenes (1–3%; up to 20% in children), Staphylococcus (S.) аureus (0–8%), anaerobes (0–10%). The role of gram-negative bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Proteus spp., Enterobacter spp., Citrobacter) in acute sinusitis is minimal, but increases with nosocomial infection, as well as in persons with immunosuppression (neutropenia, AIDS) and persons receiving repeated courses of antibacterial therapy. The causative agents of odontogenic (5–10% of all cases of sinusitis) maxillary sinusitis are: H. influenzae, less commonly Str. pneumoniae, enterobacteria and non-spore-forming anaerobes.

Therapy

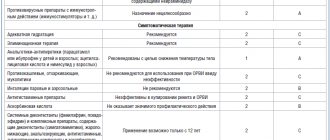

APs in combination with nasal and/or systemic decongestants, including intranasal steroids and irrigation of the nasal mucosa with saline, occupy a major place in the treatment of acute, as well as exacerbation of chronic, rhinosinusitis. Anticholinergic drugs are used: ipratropium bromide; local decongestants: oxymetazoline hydrochloride; systemic decongestants: phenylpropanolamine hydrochloride; combination of pseudoephedrine hydrochloride + acetaminophen. According to indications (for example, for the purpose of etiological diagnosis, especially if therapy is ineffective on the 3rd day, if mycosis is suspected; if there is severe pain syndrome requiring sinus decompression, etc.), sinus puncture and other treatment methods are used.

It is a misconception to prescribe (in the absence of obvious signs of allergic rhinosinusitis) antihistamines, which increase the viscosity of secretions and impede drainage of the sinuses. Another mistake is the prophylactic prescription of AP to patients with ARVI on the first day of manifestation of rhinosinusitis. An attempt to prevent bacterial complications, including those from the sinuses, is meaningless.

Antibacterial therapy. The main purpose of AT is:

- in eradication of the pathogen and restoration of sinus sterility;

- reducing the risk of chronicity (at present there is not enough data to prove the ability of AT to prevent the process from becoming chronic or to prevent the development of serious complications);

- preventing complications;

- alleviation of clinical symptoms.

In the first days of illness, when the most likely cause of the disease is viruses, in particular respiratory syncytial virus, AP is not required. If symptoms of rhinosinusitis persist for > 7–10 days, a bacterial infection can be assumed in 60% of patients. It is within this group that AT is advisable. The latter may begin earlier. The basis for this is fever and cephalgia, which are poorly responsive to analgesics.

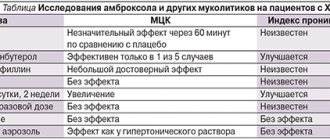

For mild and moderate acute rhinosinusitis, the therapy is the same. The drug of choice is amoxicillin. Considering the variability of absorption of the drug, to ensure high-quality treatment, it seems advisable to use a microionized form that ensures a constant absorption of 93% (solutab). Duration of therapy is 7–14 days. In the case of epidemiological significance (proposed > 5% of isolated strains) penicillin-resistant Str. pneumoniae, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of penicillin is 0.12–2.0 mg/l, the dose of amoxicillin is 3 g/day. In this case, the advantage of a highly adsorbable soluble form is obvious.

If in most cases amoxicillin is an adequate treatment for acute rhinosinusitis, then in the case of a subacute course, as well as in the presence of the following symptoms, the use of inhibitor-protected aminopenicillins (amoxicillin/clavulanate) is required.

Factors requiring the use of inhibitor-protected aminopenicillins include:

- use of AP in the previous month;

- unfavorable epidemiological situation (resistance);

- smoking;

- anamnesis data on the ineffectiveness of previous (if any) treatment;

- visiting preschool institutions;

- age less than 2 years;

- allergy to amoxicillin;

- damage to the frontal or sphenoidal sinuses;

- complicated ethmoidal sinusitis;

- duration of symptoms > 30 days.

Alternative, no less effective drugs used for intolerance to aminopenicillins include:

- macrolides (azithromycin, clarithromycin);

- cefuroxime axetil, cefprozil, cefpodoxime proxetil;

- doxycycline (use limited due to increasing resistance of pneumococcus in Russia).

Regarding the role of cephalosporins, the following should be noted. More and more data are accumulating on the relationship between the level of AP consumption and the level of resistance of microorganisms. An analytical review by J. Granizo demonstrated the adverse effect of oral cephalosporins on the spread of penicillin-resistant strains of Str. pneumoniae Therefore, their use, in the presence of amoxicillin (amoxicillin/clavulanate) and modern macrolides, should be limited to cases of ineffectiveness of AT macrolides and intolerance to amoxicillin.

Macrolides, in particular azithromycin, deserve special attention when planning AT for acute rhinosinusitis. Taking into account the reduced compliance of patients with drugs used more than once a day and for a period of more than 5 days, as well as the relatively high frequency of adverse reactions when using inhibitor-protected aminopenicillins, the drug is the drug of choice for respiratory infections. The effectiveness and safety of AT in most cases of “outpatient” rhinosinusitis in both children and adults has been confirmed by clinical practice. In particular, the same effectiveness of a single (!) dose of the microspherical form of the drug (2.0 g) and a 10-day course of AT with levofloxacin was demonstrated. The effectiveness of a 3-day course of AT with azithromycin (500 mg/day) and a 10-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanate (625 mg 3 times a day) is also comparable. A number of studies have shown that azithromycin contributed to earlier clinical improvement and reduced treatment costs, which is not surprising given the anti-inflammatory effect of macrolides.

Drugs used for severe rhinosinusitis are administered intravenously. When signs of improvement appear on days 3–5, switching to the oral form of the same drug (or amoxicillin/clavulanate when using third-generation cephalosporins) is practiced. Step therapy is effective, safe and reduces the cost of treatment.

The main drugs for the treatment of severe forms of rhinosinusitis are:

- inhibitor-protected penicillins (amoxicillin/clavulanate, preferably the microionized soluble form of Solutab);

- III generation cephalosporins (ceftriaxone, cefotaxime);

- for allergies to β-lactams - levofloxacin, moxifloxacin or chloramphenicol parenterally.

With the development of complications from the central nervous system (CNS), preference should be given to ceftriaxone (2–4 g/day in 2 divided doses) or cefotaxime (12 g/day in 4 divided doses). With the development of meningitis caused by resistant Str. pneumoniae (MIC ≥ 0.12 μg/ml), vancomycin is additionally administered (2 g/day in 4 doses). The use of moxifloxacin cannot be excluded, but there is insufficient data confirming the safety of its use.

Drugs used when AT is ineffective

- If amoxicillin or macrolides are ineffective - amoxicillin/clavulanate or third generation cephalosporins;

- if inhibitor-protected aminopenicillins and cephalosporins are ineffective - respiratory fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin, moxifloxacin) + computed tomography/endoscopy/puncture of the paranasal sinuses to exclude mycosis.

Recently, great hopes in the treatment of sinusitis caused by penicillin-resistant (MIC > 4 mg/l) pneumococci have been placed on respiratory fluoroquinolones (gemifloxacin, moxifloxacin). The activity of the drugs extends to penicillin-resistant strains of Str. pneumoniae, β-lactamase-producing strains of H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, as well as atypical and anaerobic microorganisms.

As you can see, the spectrum of APs used in the treatment of sinusitis is presented very widely, and it is quite difficult to find the line when the use of aminopenicillins is justified, and when to choose their inhibitor-protected forms, cephalosporins or fluoroquinolones. The findings of controlled studies and meta-analyses can provide significant assistance in resolving this problem.

According to their data, in mild forms of the disease, new APs show a slight advantage when compared with amoxicillin, especially with its microionized form, as well as with benzylpenicillin in the treatment of acute uncomplicated sinusitis. This conclusion is consistent with the results of a retrospective pharmacoepidemiological study performed in the USA. The overall effectiveness of therapy with first-line drugs in 17,329 patients was slightly lower and amounted to 90.1%. At the same time, in 11,773 patients who received alternative therapy, the effect was obtained in 90.8% of cases. The difference was 0.7% (95% confidence interval, 0.01%–1.40%; p < 0.05). The reason for this state of affairs is the presence in the study groups of individuals whose infectious process could have resolved without AT, since in 2/3 of cases of acute disease there is a tendency towards spontaneous resolution.

Assessment of the quality of therapy. During the initial examination and prescription of therapy, the patient should be informed about possible options for the course of the disease. In most cases, the process is resolved in a timely manner and additional medical examinations are not required.

If there is no improvement in the first 3 days of using AT, a switch is made to inhibitor-protected aminopenicillin (preferably the Solutab form) or macrolide.

In this case, as well as when the condition worsens at any time during therapy, a search is conducted for the reasons for its ineffectiveness. Most often these include: patient non-compliance, development of intracranial complications, erroneous diagnosis, resistance of the pathogen to the drug used (fungi, production of β-lactamases).

Reasons for ineffectiveness. In case of a viral infection, the main reasons for the ineffectiveness of AT for uncomplicated rhinosinusitis is the early start of therapy, before the addition of a bacterial infection (usually in the first week after the onset of ARVI symptoms).

The ineffectiveness of therapy for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis when prescribing unprotected penicillins may be explained by the production of β-lactamases by H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis. A typical reason for failure to prescribe doxycycline and macrolides is the spread of resistant strains of Str. pneumoniae and H. influenzae.

Ineffective therapy associated with the patient’s unclear adherence to the prescribed therapy regimen (non-compliance) requires special attention. Most often this is a refusal to continue therapy at the first signs of improvement observed by the 3rd day of therapy, as well as skipping the next dose and/or reducing the frequency of taking the drug. As a result of underestimation of these reasons, therapy with inhibitor-protected aminopenicillins, cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones is often prescribed.

It is known that the best compliance is observed when using drugs taken once a day. This was confirmed by the result of a recent systematic analysis, which showed compliance with the use of the drug once a day within 79 ± 14%, 2 times a day - 69 ± 15%, 3 times a day - 65 ± 16% and 4 times a day - 51 ± 20%. In this case, the difference between the first two modes was statistically insignificant. It is characteristic that compliance in the treatment of respiratory tract infections is much higher and reaches 97% (for example, when using azithromycin). The use of macrolides, according to comparative studies, is generally characterized by the best compliance.

Of no small importance is the fact that this indicator decreases as the duration of therapy increases. The best results are observed with a duration of therapy of up to 7 days. Adherence to treatment is also influenced by the patient's awareness of the severity and possible consequences of the disease, awareness of adverse reactions and their impact on the possibility of continuing therapy. Compliance is also affected by the cost of the drug and the method of acquisition. In each case, the physician must evaluate whether the patient should be encouraged to purchase an expensive antibiotic while expecting full compliance. Adherence to the prescribed treatment regimen will help reduce the actual cost of treatment. This is facilitated by the elimination of cases of apparent “ineffectiveness” of therapy leading to the prescription of alternative drugs, a reduction in the number of studies, medical visits and days of incapacity. It is these factors that explain the pharmacoeconomic advantage of short courses of therapy with new drugs that have improved pharmacokinetics (for example, azithromycin, long-acting forms of clarithromycin and soluble forms of amoxicillin/clavulanate).

Very often APs are prescribed without obvious indications. The explanation in most cases is personal experience, confirming an increase in the frequency of repeat visits in the case of non-use of AT. A number of studies deny this point of view. It turned out that patients who have good contact with a doctor, understand the possible options for the course of the disease and do not receive AT do not come back for appointments unless necessary. Moreover, there was no increase in cases of dissatisfaction with treatment.

The duration of therapy depends on the form and severity of the disease. For acute sinusitis, treatment lasts from 1 day (azithromycin 2 g - microspherical form) to 3-10 days.

conclusions

- Symptoms of rhinosinusitis are most often caused by a viral infection.

- The main causative agents of bacterial rhinosinusitis are Str. pneumoniae, H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis (more often in children).

- Diagnosis of bacterial rhinosinusitis is necessary to limit the use of AP.

- Diagnosis is based on clinical and laboratory criteria.

- The likelihood of bacterial rhinosinusitis increases when symptoms last > 10 days.

- The routine use of radiation research methods in uncomplicated forms of the disease is erroneous.

- Cultural study, purpose: to obtain local data on the resistance of pathogens and assess the possible reason for the ineffectiveness of therapy.

- AT is indicated for bacterial rhinosinusitis.

- Amoxicillin is the drug of choice; alternatives are amoxicillin/clavulanate (sulbactam), azithromycin, clarithromycin.

- The use of short courses of therapy, drugs with a single daily dose and a maximum degree of absorption of active ingredients is preferable, as it increases patient compliance, reducing the risk of adverse reactions.

For questions regarding literature, please contact the editor.

I. A. Guchev, Candidate of Medical Sciences A. A. Kolosov 421st military hospital of the Moscow Military District of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, Smolensk

What causes bacterial infections in women

If we look at the classification of bacteria that cause vaginitis and cervicitis, we can distinguish:

– aerobic, which are diagnosed in 30% of patients. However, recently doctors have been talking about an increase in the number of patients with anaerobic infections, for example gardnerella;

– intracellular mycoplasmas – ureaplasma.

With all the diversity of pathogens, it is worth noting that almost all of them are opportunistic. Associations of pathogens are common; every third woman with problems of the urogenital tract has from 6-10 pathogens. A bacterial urinary tract infection in women can have a latent and/or asymptomatic course, when a woman may not experience the characteristic ailment for a long time: vaginal discharge, itching, discomfort, and so on. At the same time, there is an increase in the resistance of pathogens to antibiotics, which makes some previously adopted regimens ineffective.

What is bacterial vaginitis and how is it different from vaginosis?

Bacterial vaginitis is a pathological infectious and inflammatory process of the vaginal mucosa of a nonspecific nature, which is accompanied by a disturbance in the composition of the microflora.

Until recently, it was believed that vaginitis could be triggered by specific pathogenic microorganisms, such as chlamydia, vaginal trichomonas and gonococcus, that is, sexually transmitted infections, but today it has been established that they are a trigger factor, while in 80% of cases the cause of vaginitis was opportunistic microflora, for example, yeast-like fungi, E. coli. The chronic course of the disease with frequent relapses was explained by the special resistance of microorganisms to therapeutic effects. To suppress opportunistic microflora, broad-spectrum antibiotics began to be used. However, the high frequency of relapses after treatment convinced doctors that such tactics were imperfect and led to the conclusion that the main problem was an imbalance of microorganisms in the vaginal environment. Research into this issue led to the emergence of the concept of “bacterial vaginosis,” which is the main cause of bacterial vaginitis. Vaginosis differs from nonspecific bacterial vaginitis in the absence of obvious inflammation and increased levels of leukocytes in smear tests.

Bacterial infection in women: consequences and complications for the body

A high concentration of opportunistic microorganisms in a woman’s lower genital tract can provoke the development of inflammatory processes in the uterus and appendages, which can subsequently cause infertility. The infectious-inflammatory process can spread to the urinary tract and cause cystitis. With frequently recurring inflammatory processes, the likelihood of infertility increases sharply. If the fallopian tubes are affected by infection, connective tissue may grow in them, causing them to narrow and making them completely or partially impassable for eggs. Bacterial vaginitis can have a negative impact on the mother's body and the condition of the fetus during pregnancy. After childbirth, bacterial vaginitis is also not uncommon, which is caused by a change in the acidity of the vaginal environment - an increase in pH, which limits the development of beneficial microflora and leads to an imbalance of microorganisms. During pregnancy, hormonal levels change significantly. During this period, the woman’s general and local immunity is weakened.

Symptoms and signs of bacterial vaginosis

The main symptoms are a homogeneous vaginal discharge with an unpleasant odor, enveloping the vaginal walls, and a feeling of discomfort. With a long process of discharge, they acquire a yellowish-greenish color and become thicker. There are no obvious signs of inflammation.