Bile duct obstruction is a blockage or obstruction of the bile ducts. By their nature, bile ducts are channels emerging from the gallbladder. Their function is to transport bile from the liver to the small intestine. This transport occurs through the pancreas.

As for bile, it is a liquid produced by the liver. This liquid may have a dark green or yellow-brown tint. The main task of bile is to break down fats. Through the sphincter of Oddi, the vast majority of liver fluid passes directly into the small intestine. The remaining volume of bile is stored inside the gallbladder. When a person eats, the gallbladder releases liver fluid to digest food and absorb fats. In addition, bile rids the liver of accumulated waste.

How does the pathology proceed?

Obstruction of the bile ducts can manifest itself in the form of weakness, itching, and yellowish coloration of the skin. In addition, the patient may have a tense pulse. The stool is characterized by an almost complete lack of color and a foul smell. Also, with this pathology, blood clotting slows down, and the urine has pronounced yellow pigments.

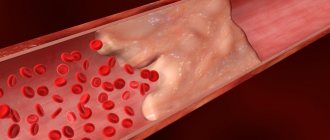

Stagnation of bile leads to expansion of the bile ducts of the liver (the organ itself enlarges). Bile acids negatively affect liver cells, causing their degeneration. There is an active release of bilirubin, which enters the bile ducts. Bilirubin then enters the bloodstream and begins to accumulate there. This component is also present in urine, because the kidneys pass it through without any problems. Since bilirubin will not enter the intestines, the patient's stool will not contain stercobilin (the cause of colorlessness), and there will be no urobilin in the urine. Over time, the mucous membrane of the bile ducts begins to produce serous fluid, and this is a sign of damage to the liver tissue. Due to the implementation of these processes, the functioning of the liver, carbohydrate and protein metabolism will be disrupted. In addition, degenerative changes will occur in the internal organs (in particular, the kidneys and heart will suffer).

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to ultrasound of the biliary tract, except for the reasons why the examination will be uninformative. Such conditional contraindications include:

- a patient with skin lesions at the time of exacerbation;

- the presence of wounds, purulent skin lesions;

- presence of scars in the abdominal area.

With such lesions, the ultrasound probe will not be in close contact with the skin, which will prevent the penetration of ultrasonic waves to the required depth, and it will be difficult to obtain complete information about the condition of the area under study.

Diagnosis of deviation

First of all, a blood test and liver function test are performed. A blood test can help rule out an incorrect diagnosis. In particular, such a measure will not allow the obstruction to be confused with inflammation of the gallbladder, inflammation of the bile duct, or increased concentrations of alkaline phosphatase or liver enzymes.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is considered a good assistant in making a diagnosis. It almost accurately detects blockage of the bile ducts. Very often, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is used for diagnostic purposes. This procedure is universal. It allows not only to examine the bile ducts, but also to take tissue for analysis.

Classification of narrowing of the bile ducts

By etiology

- Post-traumatic scar strictures;

- Strictures of biliary anastomoses;

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis;

- Secondary inflammatory strictures;

- Tumor stenoses of the bile ducts 5.1. Bismuth-Corlette classification (for proximal bile duct cancer)

- Type I. Damage to the common hepatic duct

- Type II. Damage to the confluence of the hepatic ducts.

- Type IIIA. Damage to the right hepatic duct.

- Type IIIB. Lesion of the left hepatic duct.

- Type IV. Damage to both hepatic ducts.

- 5.2. Extrahepatic bile duct cancer

- Cancer of the distal common bile duct.

- Cancer of the large duodenal nipple.

According to the degree of narrowing of the ducts

- Complete strictures.

- Incomplete strictures.

- Limited strictures (up to 1 cm).

- Widespread strictures (1 - 3 cm).

- Subtotal strictures (more than 3 cm).

- Total damage to the extrahepatic bile ducts

According to the clinical course

- With external biliary fistula.

- With jaundice.

- With cholangitis.

- With liver and kidney failure.

- With biliary cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

How is such obstruction treated?

The goal of the therapy is to completely or partially release the bile ducts. Typically, stones are removed using an endoscope during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

When it is necessary to bypass the blocking area, an operation is performed. If the blockage is caused by gallstones, the gallbladder is surgically removed. If the attending physician suspects an infection has entered the body, a course of antibiotics may be prescribed. When the blockage is caused by a cancerous tumor, specialists usually widen the canal using an endoscopic technique.

Certain treatments may be based on:

• Removal of the gallbladder; • Performing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, used to remove small stones from the bile duct or to place a stent in the duct, which helps restore the flow of bile. The stent itself is a fairly durable structure (made of plastic or metal), which is installed inside the lumen of hollow organs; This device expands the narrowed area and improves the passage of physiological fluids. • Carrying out sphincterotomy of the bile duct. A similar procedure is performed in situations where stones are present both in the gallbladder and inside the common bile duct.

The operation is performed using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Using an endoscope, an incision is made in the small intestine to widen the duct that leads to the duodenum. The resulting hole serves to remove the gallstone. As a result of this procedure, the bile flow is uncorked.

One of the main functions of the liver is bile production. The liver has two unequal lobes - right and left. The anatomical and functional (ultrasound) division of the liver into the right and left lobes differs. According to Couinaud’s classification (C. Couinaud, 1957) [1], segments I and IV are anatomically located in the right lobe, and functionally belong to the left lobe [2, 3]. Bile is collected from all segments and both lobes into lobar ducts.

In a healthy person, the intrahepatic ducts ductus hepaticus dexter (right hepatic duct) and ductus hepaticus sinister (left hepatic duct) (Fig. 1) are not visible on ultrasound; only the ductus hepaticus communis (common hepatic duct) is visible with good visualization. It connects with the ductus cysticus (cystic duct) and forms the ductus choledochus (common bile duct), which normally has a length of 5-7 cm [4].

Rice. 1. Gall bladder and bile ducts.

The common bile duct opens into the descending part of the duodenum and has sections designated according to its position relative to the duodenum and pancreas after it leaves the liver: CH1 - supraduodenal section, CH2 - retroduodenal section, CH3 - pancreatic section (located deep in the head of the pancreas). The portal of the liver is located deep in the parenchyma - this zone is projected during ultrasound examination inside the liver; this part of the common bile duct does not have a classification name (CH0, portal section) [5].

The pancreatic duct (ductus pancreaticus, Wirsung's duct) and the common bile duct at the level of the lower third of the descending duodenum are connected on the medial side. After fusion, a 2-3 mm long section is located inside the papilla duodeni major (major papilla of the descending duodenum, papilla of Vater), this is CH4 - the intramural section of the common bile duct.

Gallbladder: ultrasound approaches. The term "approach" in ultrasound refers to the position of the ultrasound transducer on the patient's body for optimal visualization of the organ.

1. Subcostal access (Fig. 2, a) . The position of the sensor is oblique below the costal arch, parallel to it. The gallbladder is most often projected along the midclavicular line. With the correct placement of the sensor, the gallbladder in this section is recessed into the liver parenchyma. By tilting the sensor in a direction closer to the spine or closer to the costal arch, you can see the lobar branches of the portal vein (right and left) and the inferior vena cava (see Fig. 2, a); these are additional landmarks for finding the gallbladder [6].

Rice . 2. Gallbladder: subcostal access (a; according to [5]); intercostal access (b) and biometry (c; according to [5]).

2. Intercostal access. The sensor is located parallel to the ribs in the intercostal space, approximately outward from the midclavicular line. With this position of the sensor (Fig. 2, b), the right lobe of the liver is mainly visible, the gallbladder is visible from below the liver, adjacent to it, adjacent to the corner of the edge of the liver. Additional landmarks are the trunk of the portal vein, which deep in the liver is divided into right and left lobar branches, and laterally to the right, the inferior vena cava.

Biometric parameters of the gallbladder and biliary tract. The size of the gallbladder is very variable (in patients of different constitutional types, depending on the filling, characteristics of smooth muscle, how it reacts to contraction).

Normal: length <120 mm in adults, can be measured both in subcostal (somewhat shorter, since it is more difficult to bring out the entire length) and in intercostal approaches. The transverse diameter is normally <40 mm and is measured strictly at right angles to the length. Fasting wall thickness <2 mm, contracted bladder wall thickness <4 mm (if the patient ate food on the day of examination) [7, 8].

The gallbladder wall should be measured at the site closest to the transducer, as the dorsal reinforcement effect may result in the appearance of greater thickness. If this is an intercostal approach (Fig. 2, c) , then the dorsal (anterior) wall of the gallbladder should be measured - adjacent to the visceral surface of the liver, and not the ventral (posterior).

Bile ducts. In Fig. 3, the right and left hepatic ducts and the ducts flowing into them are clearly visible, since they are dilated as a result of obstruction of the bile ducts distally beyond the liver (normally not detected) [9, 10].

Rice . 3. Intrahepatic bile ducts (identified against the background of obstruction of the common bile duct).

The walls of large and small ducts in Fig . 5 are uneven, this is detected only in the case of obstruction. The common bile duct is located outside the liver, in Fig. 4 it is curved, adjacent to the visceral surface of the liver, its right section is embedded in the head of the pancreas [7].

Rice. 4. Common bile duct.

In Fig. 4, additional landmarks are also visible: a large venous vessel - the inferior vena cava, posterior to which are located the right renal artery, the right branch of the hepatic artery and the portal vein. The normal diameter of the common bile duct is <6 mm. After cholecystectomy <9 mm (according to B. Blok) is compensation for the possibility of bile accumulation in the gallbladder.

In Fig. 5 areas in the yellow circle on the echograms correspond to the area in the yellow circle in the diagram [11]. The most superficial structure is the common hepatic duct; the right hepatic artery crosses it deeper at a right angle, and the portal vein is located even deeper. Normally, the portal vein (about 6 mm) is thicker than the common hepatic duct (about 4 mm). In the diagram and on the echogram in the red circle, the area in which the cystic duct connects with the common hepatic duct is the place of formation of the common bile duct.

Rice. 5. Common hepatic and common bile ducts (according to [11]).

On the echogram in Fig. 5 the gallbladder and the so-called Mickey Mouse are visible, whose ears are sections of the cystic and common bile ducts, the head is a section of the common bile duct, and the body is a section of the portal vein.

Parasagittal approach (see Fig. 5) : the common bile duct and the gastroduodenal artery are directed at an acute angle to each other (the common bile duct is green, the gastroduodenal artery is red).

In Fig. 6 on echogram 1 the head of “Mickey Mouse” is visible: at the gate of the liver there are ears (the right one is the common bile duct or in some cases the common hepatic duct, the left one is the proper hepatic artery), the head is the portal vein, the torso is the inferior vena cava. The supraduodenal part of the common bile duct is shown in yellow on the echogram and diagram [12].

Rice . 6. Sections of the common bile duct (according to [12]).

On echogram 2 (see Fig. 6) , the portal vein is identified, parallel to it is the common bile duct (the supraduodenal and retroduodenal parts are visible), the upper part of the duodenum, the pylorus, and the pancreas.

Echogram 3 (see Fig. 6) shows a transverse scan - the pancreas is well recognizable due to the splenic vein, two anechoic points are visible at the level of the head of the pancreas: the lower one is the pancreatic section of the common bile duct, the upper one is the gastroduodenal artery. The inferior vena cava, aorta and superior mesenteric artery are also identified. The pancreatic part of the common bile duct is shown in red on the echogram and diagram.

The intramural part of the common bile duct is located in the wall of the descending duodenum and is normally not visible (Fig. 7) .

Rice . 7. Examples of echograms of the common bile duct.

Sphincter apparatus of the biliary tract. In Fig. Figure 8 shows small folds of the mucous membrane of the gallbladder, spiral folds inside the cystic duct (Heister valves).

If you dissect the mucous membrane of the duodenum, you can see sphincters - smooth muscle fibers covering the ducts: the sphincter of the common bile duct (Aschof), the sphincter of the pancreatic duct and, after their fusion, the sphincter of the hepatic-pancreatic ampulla, or the sphincter of Oddi (see Fig. 8; Fig. . 9) . In Fig. 8 also indicates Lütkens' sphincter - between the neck of the gallbladder and the cystic duct.

Rice . 8. Sphincter apparatus of the biliary tract.

Rice . 9. Anatomy of the major duodenal papilla (papilla of Vater) [4].

Normally, these structures are not visible during ultrasound examination [6].

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Surgical relief of obstruction

If a person is diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, doctors install a stent in the narrowed area of the bile duct. First, specialists insert an endoscope into the esophagus, and then pass it into the stomach and at the very end reach the duodenum. Such actions help to study the blocking site for proper stent placement. Before taking an x-ray, a dye is injected into the patient's body, which will also ensure the correct placement of the device. If obstruction recurs, the medical device is replaced.

Causes of strictures

Most often, there are three groups of causes of the disease:

- traumatic - develop after surgical interventions: cholecystectomy, endoscopic manipulation, resection of the stomach or liver;

- inflammatory - they are caused by cicatricial changes in the walls of the ducts in various diseases (chronic pancreatitis, low duodenal ulcers, parasitic liver diseases, etc.);

- tumor - strictures that occur with cancer of the gallbladder or extrahepatic bile ducts.

Treatment in the department of thoracoabdominal surgery and oncology of the Russian Scientific Center for Surgery

Treatment of tumors and strictures of the bile ducts in our department is carried out within the framework of the compulsory medical insurance , voluntary medical insurance, VMP , as well as on a commercial basis . Find out how to get treatment at the department of thoracoabdominal surgery and oncology of the Russian Scientific Center for Surgery.

We provide surgical treatment with highly qualified doctors , the best modern equipment and attentive staff. Read patient reviews here .

To schedule a consultation, call:

+7 (499) 248 13 91 +7 (903) 728 24 52 +7 (499) 248 15 55

Submit a request for a consultation by filling out the form on our website and attaching the necessary documents.

Treatment of strictures and tumors of the bile ducts

Currently, various types of treatment are used: from drainage to reconstructive operations. However, there is no systematic approach that takes into account both the main characteristics of ductal stenosis and the advantages and disadvantages of a particular surgical treatment technique for a particular patient. Today, an individual approach to each clinical situation is required, allowing the use of both modern minimally invasive techniques and time-tested reconstructive operations.

For non-tumor injuries of the bile ducts, the following types of surgical interventions are distinguished:

- drainage operations (bile diversion to the outside);

- reconstructive operations;

- reconstructive operations.

Drainage operations include: drainage of the common bile duct according to Vishnevsky, Kerta, Halsted, drainage of the proximal end of the crossed duct, percutaneous - transhepatic drainage.

In case of marginal injuries, preference is given to T-shaped drainage compared to other methods, since it has been proven that in choledochotomies completed with T-shaped drainage, neither gross deformations of the hepaticocholedochus nor its stricture at the site of the drainage were detected in the long term.

When the tumor affects the distal part of the common bile duct, preference is given to gastropancreatoduodenal resection.