Abdominal ischemia (mesenteric thrombosis, acute intestinal ischemia, intestinal circulatory failure) occurs when blood flow through the arteries that supply blood to the intestines slows or stops. This condition has many potential causes, including a clot blocking the artery or narrowing of the artery due to the development of cholesterol plaques. Blockages can also occur in veins, but they are less common.

Regardless of the cause, decreased blood flow to the gastrointestinal tract leaves tissues without sufficient oxygen, causing cell dysfunction and cell death. If the damage to the intestinal wall is severe enough, intestinal gangrene develops, followed by its rupture (perforation), resulting in fecal peritonitis and death.

Saving a person with mesenteric thrombosis is possible only with timely correct diagnosis, followed by removal of the blood clot and assessment of intestinal viability. With conventional symptomatic treatment, mortality reaches 99%, with surgery to remove the intestine - 80%, with timely removal of the blood clot and control of the intestine - 25%.

Treatment approach at the Innovative Vascular Center

Timely diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia allows for adequate treatment and saving a person’s life. In our clinic, if mesenteric ischemia is suspected, angiography is urgently performed and the blood clot is removed from the intestinal arteries. Only such treatment gives the patient a chance to survive. If enough time has passed since the onset of the disease, then restoration of blood circulation and laparoscopy are performed, which makes it possible to determine the need to remove dead sections of the intestine. Without treatment, all patients die. With treatment, more than half can be saved.

Types of inflammatory bowel diseases

Intestinal inflammation cannot go away on its own

Among all gastrointestinal diseases, intestinal inflammation ranks second in frequency of occurrence, it affects all age and social groups, and occurs with equal frequency in men and women. According to the location of inflammation, it is divided into the following diseases:

- Enteritis is an inflammatory process that affects the small intestine.

- Duodenitis - inflammation affects the duodenum.

- Colitis – inflammation occurs in the large intestine.

- Enterocolitis - inflammation spreads to almost the entire intestine.

These diseases can be acute or chronic, depending on this there should be a completely different approach and treatment method to them.

Causes of acute intestinal ischemia

- Atherosclerosis of the intestinal arteries can lead to their thrombosis with the subsequent development of mesenteric ischemia. If there are signs of coronary heart disease, atherosclerotic lesions of the arteries of the legs in a patient, systemic atherosclerosis can be implied and, accordingly, the risk of abdominal ischemia can be taken into account.

- High or low blood pressure increases the risk of mesenteric thrombosis and intestinal ischemia

- Heart failure and atrial fibrillation increase the risk of intestinal arterial embolism (transfer of a blood clot from the heart to the arteries) and acute intestinal ischemia.

- Increased blood clotting in thrombophilia, sickle cell anemia and antiphospholipid syndrome.

- Cocaine and methamphetamine use can cause intestinal vasospasm and intestinal ischemia.

Diagnosis of intestinal inflammation

Gastroenterologist is a doctor who treats gastrointestinal diseases

A gastroenterologist should treat intestinal inflammation and should be contacted if the above symptoms appear in any degree of their manifestation. To clarify the diagnosis and to exclude diseases of a different profile with similar symptoms (oncology, infections), the doctor prescribes an examination. This may include:

- Endoscopy of the stomach and duodenum with a biopsy of the mucous membrane, if necessary - the condition of the mucous membrane is analyzed.

- Colonoscopy – using a colonoscope inserted through the rectum, the localization of inflammation in the large intestine is assessed.

- Blood test for ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) - the intensity of the inflammatory process is assessed.

- Coprogram – assessment of intestinal enzymatic function.

- Examination of stool for the absence or presence of bacteria, their sensitivity to groups of antibiotics.

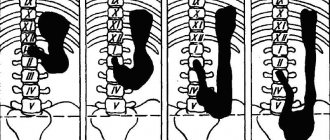

Clinical forms of mesenteric thrombosis

- Vascular thrombosis of the colon (ischemic colitis)

This most common type of intestinal ischemia occurs when blood flow to the colon is reduced. It is most often observed in people over 60 years of age, although it can develop at any age. Signs and symptoms of colonic ischemia include bleeding from the anus and sudden cramping pain in the abdomen.

- Acute small bowel ischemia

This type of intestinal ischemia is usually associated with blockage of blood flow in the superior mesenteric artery. It has an abrupt onset. I am worried about severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting. The condition progressively worsens and the patient dies in the coming days.

- Chronic insufficiency of intestinal blood supply

Chronic abdominal (mesenteric) ischemia is sometimes called intestinal angina (angina pectoris). Develops as a result of the development of atherosclerotic plaques in the intestinal arteries. This process develops slowly, complaints are in the nature of digestive disorders, spasms in the intestines. A potentially dangerous complication of chronic mesenteric ischemia is the development of blood clots in the affected arteries, which block blood flow and cause acute abdominal ischemia.

- Venous abdominal ischemia

Develops with thrombosis of the mesenteric veins against the background of various diseases of the abdominal organs. When the intestinal veins are blocked, blood stagnates in the intestines, causing swelling of the intestines and bleeding of the mucous membrane. A complete block of venous outflow leads to the death of sections of the intestine with the development of peritonitis.

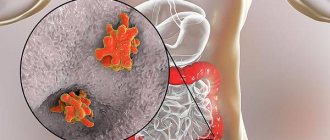

Crohn's disease

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic progressive inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract, characterized by inflammatory changes in any part of the digestive tube and, often, the development of complications - fistulas, strictures, infiltrates, as well as perianal lesions.

This pathology, along with ulcerative colitis, is included in the group of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD).

Epidemiology of CD.

Just a few decades ago, the disease was considered rare. A practicing gastroenterologist with extensive experience over many years of work may never have seen a patient with this disease; Coloproctologist surgeons were somewhat more likely to encounter CD.

The situation has changed in the last 20-25 years: there has been an increase in the prevalence and incidence of CD worldwide, with the largest number of cases recorded in North America and Europe. Thus, the prevalence of CD in Canada (one of the highest in the world) is 363 patients per 100 thousand population. Data on the prevalence of this disease in the Russian Federation are limited to small studies.

The prevalence of CD is higher in northern latitudes and in the west. Two peaks of incidence have been described: the age group of 20-30 years and 60-70 years. CD occurs equally often in men and women.

Etiology (origin) of CD.

CD has an unknown etiology, which means there is no precise knowledge about the origin of this disease. The hypothesis that has the greatest support from the scientific world is that in individuals with a hereditary predisposition, under the influence of environmental factors (smoking, nutrition, use of certain medications), uncontrolled immune inflammation develops in some part(s) of the gastrointestinal tract.

Hereditary predisposition does not necessarily imply an indication of CD in relatives; it is not determined by any one gene. A whole combination of different genes takes part in the formation of CD, but without the influence of environmental factors, the disease may never manifest itself.

If these factors take place, then in genetically predisposed individuals, eventually, the immune response to the contents of the intestine (bacterial antigens, food components and other substances that have entered the intestinal lumen) becomes excessive. As a result, protective (anti-inflammatory) mechanisms are insufficient, and intestinal inflammation develops.

Clinical picture of CD.

The symptoms of CD are varied and do not always allow one to immediately suspect intestinal disease. For example, in a number of patients, the first manifestations of the disease are not intestinal disorders at all, but joint pain, eye lesions or skin manifestations. Quite often there are situations when the patient, before the diagnosis was made, episodically or regularly consulted proctologists about recurrent anal fissures, paraproctitis or fistulas.

And yet, CD is most often manifested by gastrointestinal symptoms: abdominal pain, bowel movements, unexplained weight loss, and causeless increase in body temperature are the most characteristic signs of this disease.

Violation of the frequency and nature of stool. CD is characterized by chronic stool disorder. Stool varies from mushy once a day to liquid multiple times. Unexpressed short-term episodes of stool disorder over many years usually cause little concern to patients and rarely cause a visit to the doctor. Despite the fact that in most cases this is so-called functional diarrhea (for example, associated with an excess of certain fruits and berries in the diet or as a result of poor tolerance to milk sugar), sometimes such loose stools are a sign of existing CD.

Blood in the stool may be present, but is not always common even in very severe cases of the disease. An admixture of mucus in the stool is not a symptom of the disease, although it can be observed when the inflammatory process is active in the colon. Some forms of Crohn's disease are even characterized by constipation, which may be one of the early signs of the formation of a complication of the disease - intestinal stricture. Also, with strictures, a change in the shape of the stool to “ribbon-like” may be observed.

If the rectum and sigmoid colon are affected, the patient may be bothered by so-called “false urges”: going to the toilet is not accompanied by the appearance of stool, and during bowel movements mucus, blood, or simply gases are released.

The urgency of the urge to defecate often worries patients with active CD, but can also be observed in other diseases (not related to intestinal inflammation).

Note : a change in the consistency and shape of stool is not a pathognomonic (defining, distinctive) sign of CD, since it is often observed in non-inflammatory bowel diseases. The presence of blood in the stool is an important symptom that requires consultation with a doctor.

Stomach ache. Abdominal pain in CD is common, up to 80% of cases, ranging from mild to very severe. A small proportion of patients with this disease almost never experience abdominal pain. The cause of abdominal pain is the spread of the inflammation process to the submucosal nerve plexus of the intestine or even deeper. With a superficial inflammatory process (affecting the intestinal mucosa), there may be no abdominal pain.

Abdominal pain usually occurs during an exacerbation of the disease, and can also occur at night, causing the patient to wake up. They are often associated with stool - they increase before defecation and decrease after bowel movement. However, it is often not possible to establish a clear connection between pain and stool.

Note : abdominal pain during the period of proven remission of CD (including endoscopic and MRI remission) can be observed when this disease is combined with irritable bowel syndrome.

Loss of body weight. Underweight is observed in more than half of patients with CD even before diagnosis. Gradual, unmotivated weight loss is sometimes a motivating reason for the patient and doctor to examine the gastrointestinal tract. Weight loss in CD can occur for several reasons:

- decreased appetite and (as a consequence) daily caloric intake;

- inflammatory process in the small intestine with impaired absorption of nutrients;

- the severity of the systemic inflammatory process, when the processes of catabolism (decomposition of nutrients) begin to predominate over anabolism (synthesis);

- some other conditions associated with CD that lead to impaired absorption or accelerated movement of food gruel through the small intestine (for example, bacterial overgrowth syndrome).

Note : It should be remembered that normal or even overweight does not exclude the diagnosis of CD. Overweight and obesity are a common problem in the modern world; in developed countries, up to 40-50% of the population have problems with excess weight. In the absence of reasons for weight loss, patients with CD who are overweight can remain at their previous weight even during an exacerbation of the disease. Treatment with steroid hormones can lead to weight gain and progression to obesity.

Nausea and vomiting. These symptoms are not very characteristic of CD, but can occur when this disease affects the stomach, duodenum, or when a complication develops - stricture. In the case of a stricture, nausea and vomiting are usually associated with episodes of severe (often sudden) abdominal pain. Such symptoms can be observed with significant narrowing of the intestinal lumen and the development of intestinal obstruction.

Increased body temperature. One of the early signs of CD before diagnosis may be an unexplained increase in body temperature. It can be episodic or constant, body temperature can reach high values (more than 38C0) or stay around 37.0-37.5C0. Such patients are often examined by various specialists to determine the cause of the elevated body temperature.

The reason for the increase in body temperature is the inflammatory process in the intestines, as well as the development of purulent complications (abscess, paraproctitis). Elevated body temperature combined with high levels of laboratory markers of inflammation (C-reactive protein) indicates so-called “systemic inflammation.” However, even in the presence of erosions or ulcers on the mucous membrane, body temperature and laboratory markers of inflammation may remain within normal values. In this case, we are talking only about “intestinal inflammation”.

Perianal lesions. Perianal lesions include anal fissures, perianal fistulas and paraproctitis.

A feature of anal fissures in CD is their appearance against the background of unformed stool (unlike fissures due to constipation), and frequent relapses even after surgery.

If perianal lesions are detected in a patient with bowel movements and other gastrointestinal complaints, Crohn's disease should first be suspected and further examination recommended.

Extraintestinal manifestations. The variety of extraintestinal manifestations in CD often leads to the fact that the patient is treated by doctors of various specialties, with the exception of a gastroenterologist, before diagnosis is made.

1) Joint pain is one of the most common extraintestinal manifestations of CD. Both large joints (knees, elbows, shoulders, etc.) and small ones (joints of the hands, feet) can be affected. The severity of manifestations varies from painful movements in the joints (arthralgia) to swelling, redness, limited mobility in the joint and severe pain (arthritis). Arthritis of large joints in CD is closely related to the activity of the disease; pain resolves with treatment. Pain in the small joints of the hands or feet can be bothersome even with complete remission of CD.

Separately, we should highlight pain in the sacroiliac joints (so-called sacroiliitis) and pain along the spinal column (spondyloarthritis). These extraintestinal manifestations of CD are also not associated with disease activity and can be observed even during remission.

2) Eye lesions – uveitis, iritis, iridocyclitis, episcleritis. Usually associated with disease activity and resolve with therapy.

3) Skin lesions - pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum. Pyoderma gangrenosum is an ulcerative skin lesion not associated with infection against the background of CD activity. Erythema nodosum is characterized by inflammation of the blood vessels of the skin and subcutaneous fat and manifests itself in the form of dense, painful nodes, somewhat elevated above the skin with redness and a local (local) increase in temperature. Typical localization is the anterior outer surface of the legs. Like pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum is associated with CD activity, completely disappearing with adequate therapy

4) Damage to the mucous membranes. A typical manifestation is aphthous stomatitis - painful ulcers (aphthous) on the oral mucosa. Stomatitis is also associated with the activity of CD; during the period of remission, it practically does not bother patients.

5) Liver damage. Among the extraintestinal manifestations of CD, some authors consider primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a chronic inflammatory disease of the bile ducts, leading to their damage and the formation of strictures. The outcome of the disease is the development of liver cirrhosis. According to other ideas, PSC is not an extraintestinal manifestation of CD, but only an associated disease that occurs simultaneously with intestinal pathology.

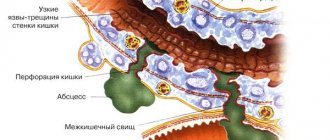

Complications

The diagnosis of CD is sometimes made for the first time only when complications arise. Often the patient is seen by a doctor with another pathology, but the appearance of complications typical for CD is the basis for revising the diagnosis.

The following complications are typical for CD:

- stricture, i.e. narrowing of the intestinal lumen, fistulas;

- fistula - the appearance of a passage between the intestine and other organs. fistulas can be external (enterocutaneous) and internal (interintestinal, enterovesical, recto-vaginal, etc.);

- abscesses - the formation of delimited purulent foci between the loops of the intestine, in the abdominal cavity, in the pelvis;

- intestinal infiltrate - the formation of a conglomerate from inflamed intestinal loops, sometimes involving other organs and structures;

- intestinal bleeding;

- intestinal obstruction – occurs with the development and progression of a stricture (or stricture + infiltrate).

The symptoms described in this section do not exhaust the variety of complaints that can be observed with CD. At the same time, one patient does not necessarily have to have all of the listed symptoms. On the contrary, very often the manifestations of the disease can be “blurred”, dim, sometimes limited to 1-2 clinical signs.

Classification of BC.

The practical classification of CD is based on the identification of individual forms of the disease depending on the location of the lesion and its form.

Based on the location of the lesion, the following types of CD are distinguished:

- colitis (colon damage);

- terminal ileitis (damage to the terminal ileum);

- ileocolitis (colitis + terminal ileitis);

- damage to the upper gastrointestinal tract (small intestine above the terminal ileum, stomach, esophagus, oral cavity).

It is customary to distinguish the following forms (phenotypes) of CD:

- inflammatory (luminal);

- stricturing (stenotic);

- penetrating (fistula);

- CD with perianal lesions (fistulas, anal fissures, paraproctitis).

Diagnosis of CD.

There is no unique method for diagnosing CD that would allow this diagnosis to be made with 100% accuracy. The diagnosis is established based on a combination of data on the medical history, patient complaints, results of laboratory and instrumental research methods. Below we will examine in more detail some laboratory tests and instrumental research methods.

Stool analysis for fecal calprotectin. The method is based on assessing the content of calprotectin in feces, a protein secreted by neutrophil leukocytes, and, to a lesser extent, by monocytes and macrophages. These are cells that respond to inflammation and damage, including in the intestinal mucosa. In response to inflammation of any origin, activated cells (primarily neutrophils) migrate to the lesion and begin to secrete calprotectin. In this case, calprotectin is determined by test systems in stool.

Fecal calprotectin is not a marker of CD (!!!). If its level is elevated, one can suspect the presence of inflammation in the intestines and send the patient for an endoscopic examination. Moderately elevated values of calprotectin are observed, for example, in celiac disease, autoimmune gastritis, and consumption of large doses of alcohol. Significantly increased concentrations are observed in inflammatory bowel diseases, bacterial infections of the gastrointestinal tract, diverticula and cancer, and chronic use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

During exacerbation of CD, the level of fecal calprotectin increases in 95% of patients. International guidelines for the diagnosis of this disease recommend considering a fecal calprotectin level >150 μg/g as a possible sign of CD, requiring additional examination of the intestines. During remission of CD, fecal calprotectin levels usually remain normal unless there are other reasons for its increase.

Sometimes, together with fecal calprotectin, fecal lactoferrin is used - another inflammatory protein, which, along with calprotectin, remains in the stool for a long time and is little decomposed by the enzymes of intestinal microorganisms.

C-reactive protein. An indicator of a biochemical blood test, an increase in which indicates the presence of signs of a systemic inflammatory process of any origin. Unfortunately, this indicator cannot be considered as a diagnostic marker of CD, but it is often used to assess disease activity and monitor the effectiveness of treatment.

Antibodies to Saccharomycetes. Antibodies to baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ASCA) are a group of antibodies often found in CD. According to studies, up to 25-30% of patients with CD have elevated levels of these antibodies. In 255 cases, ASCA was detected in relatives of patients with CD. At the same time, currently, none of the international guidelines recommend the use of this marker in routine clinical practice, since ASCA cannot be considered as a marker of CD. These antibodies are found in other diseases (although less frequently than in CD) and even in healthy individuals. A suitable “niche” for the use of this laboratory indicator can be considered complex cases where it is impossible to distinguish CD and another disease with high accuracy.

Videocolonoscopy. It would be more accurate to call this method “ileocolonoscopy,” which implies examination of not only the colon, but also the final (terminal) section of the ileum. With CD in the acute phase, the following signs of the disease can be found during colonoscopy:

- erosions, including aphthous erosions (aphthae);

- ulcers;

- strictures;

- openings of fistula tracts.

The method allows diagnosing CD in most cases, however, it is not ideal. Lesions of the gastrointestinal tract within CD can be localized in the small intestine, above the area accessible for inspection during ileocolonoscopy. In addition, changes in the mucous membrane may be minimal and nonspecific, while the main process of inflammation is localized in the intestinal wall. Finally, examination of the ileum cannot always be performed, including for technical reasons.

Examination of the small intestine using a video capsule . Endovideocapsule examination allows for examination of the small intestine, which is very important if CD of this segment of the digestive tube is suspected. The capsule is a disposable miniature video camera enclosed in a smooth polymer shell along with light sources, a transmitting antenna and batteries. The capsule is swallowed by the patient, moves under the influence of gastrointestinal motility, passes through the small intestine and is excreted through the anus. During the passage, filming is carried out, which makes it possible to identify aphthous, erosive or ulcerative defects in small intestinal lesions within the framework of CD.

The advantages of the method include its informativeness, non-invasiveness, the possibility of re-evaluation of the resulting video image (including by several specialists), ease of preparation and easy tolerability by the subjects, and the absence of harmful effects on the human body.

There are also disadvantages. Thus, it is not recommended to perform an endovideocapsule if a stricture of the small intestine is suspected - it may simply get stuck, which will require surgical intervention. With this study, it is impossible to take a biopsy; image analysis sometimes takes a very long time. In addition, the image itself is limited only by what is in the camera's field of view - the intestinal mucosa.

Capsule examination is recommended only for assessing the condition of the small intestine, and does not replace ileocolonoscopy.

Enteroscopy. More precisely, double-balloon enteroscopy, which allows you to examine the small intestine along its entire length, perform biopsy and therapeutic manipulations (in particular, stopping bleeding). To carry out the procedure, a telescopic system is used, consisting of an endoscope (enteroscope) and an external tube with a system of balloons and an air-injecting pump. This is a complex, long-term study, which is performed only under anesthesia, most often in two stages, with an interval of 12 hours, in a hospital setting.

Esophagogastroscopy (EGD) or gastroscopy. A traditional and frequently used method for diagnosing diseases of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum, which can be used if CD is suspected affecting these organs. In typical cases, aphthous erosions, ulcers (including slit-like), strictures, and openings of fistula tracts are detected.

MRI enterography or hydro-MRI. The method is based on the assessment of the intestine and surrounding tissues during magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with the sequential administration of two types of contrast agents (one drug is taken orally, the second is administered intravenously). As a result, the examining physician receives images of the small intestine and, additionally, the large intestine. Patients with CD may show signs of inflammation in the intestinal wall, strictures, infiltrates, fistulous tracts, etc. The method is not an alternative to ileocolonoscopy, since it does not allow a detailed assessment of the intestinal mucosa, to identify aphthae, erosions and superficial ulcers. If MRI enterography is not possible, CT enterography may be performed.

Ultrasound examination of the intestine. Ultrasound examination (ultrasound) is not one of the main methods for diagnosing CD. At the same time, some ultrasound modes have recently been considered as valuable non-invasive techniques for assessing the condition of the intestinal wall.

With transabdominal ultrasound using various sensors, it is possible to assess the safety of the normal layers of the intestinal wall and its thickness. elastography allows you to assess tissue elasticity, which is very important in the diagnosis of strictures in CD.

Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) makes it possible to examine the wall of the rectum, assess the integrity of its division into layers, and identify fistulous tracts, paraproctitis and abscesses. TRUS is generally comparable in information content to magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvic organs, which is also used in the diagnosis of CD with perianal lesions.

X-ray examination. X-ray (Rg) diagnosis for CD includes plain radiography of the abdominal organs (if intestinal obstruction is suspected), X-ray contrast examination of the small intestine with a barium suspension (if it is impossible to perform MRI or CT enterography) and fistulography (assessment of external fistulas). These methods are mainly used to exclude complications of CD.

Histological examination. An important stage in the diagnosis of CD is histological examination of biopsies of the intestine, stomach, esophagus or oral cavity. Typical histological signs of CD (sarcoid granuloma, giant slit-like ulcers, focal and intermittent inflammation, as well as its transmurality - penetration into the deep layers of the intestinal wall) are not always found. Therefore, the absence of typical histological signs of the disease does not exclude the diagnosis of CD.

As mentioned above, the diagnosis of CD is based on a combination of several signs: for example, typical endoscopic and histological changes.

Differential diagnosis of CD.

In the medical world, this term refers to the need to distinguish CD from other diseases at the stage of diagnosis. And here you can list a huge variety of diseases that imitate CD. We will try to consider the most common pathologies that may be “similar” to CD in their manifestations.

1) Irritable bowel syndrome. A disease of the colon of non-inflammatory origin, which is characterized by typical abdominal pain, stool disorders (diarrhea, constipation, or a combination of both) and a number of other symptoms. Unlike CD, with irritable bowel syndrome there are no signs of intestinal inflammation and erosive and ulcerative lesions of the colon mucosa typical for CD.

2) Intestinal infection. The appearance of loose stools (including bloody stools). Abdominal pain, as well as increased body temperature, are very often a manifestation of acute or chronic intestinal infection. While an acute intestinal infection usually resolves within the next few days or weeks, chronic infections (eg, yersineosis or pseudotuberculosis) can mimic chronic inflammatory bowel disease, primarily CD. Taking antibacterial drugs is often associated with the addition of a bacterial infection Clostridium (Clostridioides) difficile, the spores of which in the intestines can germinate into vegetative forms producing toxins. Toxins A and B cause the development of inflammation, damage to the intestinal mucosa with the appearance of symptoms similar to CD - frequent loose stools, sometimes with blood, abdominal pain, increased body temperature. An endoscopic examination of the colon may reveal swelling, redness, bleeding of the mucous membrane, as well as erosions and ulcers.

3) Damage to the mucous membrane by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs are widely used to relieve pain of various origins (headaches, joint pain, regular pain, etc.). It is known that most drugs from this group can damage the mucous membrane of the gastrointestinal tract: stomach, small and large intestine. Depending on the degree of damage, the severity of symptoms varies. Fecal calprotectin may indicate the presence of inflammation in the intestines, and colonoscopy may reveal erosions and ulcers in the colon and ileum.

4) Ulcerative colitis.

I would like to devote a few words to various “finds” when performing colonoscopy. Lymphofollicular hyperplasia of the ileum is not a sign of CD, even if the patient is bothered by unclear abdominal pain and stool disturbances. Swelling or atrophy of the ileal villi in the absence of erosions or ulcers does not indicate CD.

Moreover, if an endoscopist in a colonoscopy report describes the changes found as “terminal ileitis,” in the vast majority of cases this does not equal a diagnosis of CD. Why? The fact is that usually “terminal ileitis” is only a description of the anatomical zone (terminal ileum), where some signs of inflammation were found (sometimes only minimal swelling or redness of the mucous membrane). In CD, “terminal ileitis” is the typical sign of disease (erosion or ulceration) found in the terminal ileum.

Treatment of CD.

1. Lifestyle changes. And the main point in this section is quitting smoking tobacco.

A) Tobacco smoking is a known factor influencing the occurrence and course of CD. It has been proven that the risk of developing CD in smoking patients is 2 times higher than in non-smokers or those who have quit smoking. In addition, smoking worsens the course of CD: it increases the risk of exacerbation of the disease, the need for steroid hormones and immunosuppressants, as well as for surgical intervention. Smoking patients with CD are more likely to experience complicated forms of the disease (stricturing, penetrating), perianal lesions and involvement of the small intestine, and the likelihood of developing postoperative relapses is 2 times higher than in non-smokers.

The negative effect of smoking is largely due to the factor of tobacco use itself rather than the number of cigarettes smoked. Strong evidence of the negative impact of smoking can be considered a more favorable course of CD when quitting smoking - the need for immunosuppressants is reduced and the risk of exacerbation is reduced by 65%.

B) Changing the nature of nutrition. And this point is not about diets, but about nutrition principles. It is known that certain dietary habits can influence the likelihood of occurrence or the course of CD.

Thus, clinical studies indicate that individuals with CD were less likely to consume fruits and vegetables before the onset of the disease. Among patients with CD in remission, exacerbations within 6 months were 40% less likely if the diet contained more dietary fiber (24 g versus 10 g/day). Patients with CD should limit their consumption of foods containing maltodextrins and artificial sweeteners, as well as processed foods containing titanium dioxide and sulfites. More information about the impact of nutrition on CD and inflammatory bowel disease in general can be found in the article “Nutrition for patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: new recommendations.”

Nutrition and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: General Questions

2. Drug treatment of CD.

Drug therapy for CD includes anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapy. Below are the groups of drugs that are used to treat this disease:

- aminosalicylates (mesalazine) – the effectiveness of drugs in this group is low, indications for use in CD are limited;

- antibiotics (metronidazole, ciprofloxacin) – used for perianal lesions as part of CD or the development of complications of the disease;

- immunosuppressants (thiopurines, methotrexate);

- hormonal drugs (budesonide, prednisolone, methylprednisolone)

- genetic engineering biological therapy is the most modern anti-inflammatory therapy for severe and complicated forms of CD.

In the last decade, increased interest in inflammatory bowel diseases around the world has created the prerequisites for the development and introduction into clinical practice of new drugs for the treatment of CD. A large number of new molecules are currently undergoing clinical trials.

3. Surgical treatment of CD. It is not a treatment for CD itself; surgical intervention is usually necessary in case of complications of the disease or perianal lesions. Surgery to remove the affected part of the intestine does not lead to a cure for CD; patients often experience postoperative relapse.

Surgery in patients with CD is indicated:

- for acute complications of the disease: intestinal perforation, toxic dilatation of the colon and intestinal bleeding without effect from conservative therapy;

- for chronic complications of the disease: internal and external intestinal fistulas, infiltrates, strictures with impaired intestinal patency, tumors;

- ineffectiveness of all methods of conservative therapy;

- some perianal lesions.

CD is treated by a gastroenterologist, coloproctologist surgeon and other specialists (rheumatologist, ophthalmologist, dermatologist) in the presence of extraintestinal manifestations.

BC forecast.

The prognosis is determined by the severity, form of CD and the presence of complications, as well as response to therapy. Patients with mild to moderate disease (up to 3/4 of all CD cases) rarely undergo surgery and respond well to basic therapy. Severe disease may require surgical treatment and modern genetic engineering biological therapy. CD is not an oncological disease, and in most cases does not affect life expectancy.

Complications of mesenteric thrombosis

- Gangrene of the intestine. If the blood flow to the intestines is completely blocked, then its death develops.

- Perforation. The dead section of intestine may rupture. As a result, the contents of the intestines spill into the abdominal cavity, causing an infectious process in the peritoneum (peritonitis).

- Scar changes in the intestinal wall. Sometimes these dangerous complications do not develop, but the damaged intestinal wall is replaced by a scar, causing narrowing of the intestinal tube and the development of intestinal obstruction.