The human lungs consist of lobes, which, in turn, consist of segments: separate sections of parenchyma, each of which contains a segmental bronchus and a separate branch of the pulmonary artery. Segmental pneumonia involves damage to an entire segment of the lungs. The disease is characterized by an acute onset and severe course. Segmental pneumonia requires urgent treatment, as it often has serious complications. In Moscow, treatment of segmental pneumonia is successfully performed at the Yusupov Hospital, whose therapists and pulmonologists use modern effective methods of treating the disease in their work.

Features of bilateral pneumonia

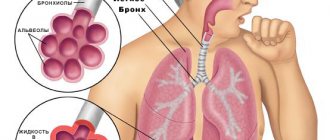

The lungs are a paired organ whose main task is breathing.

This process occurs in the alveoli of the lungs, where gas exchange occurs with the pulmonary capillaries. Thus, inhaled oxygen easily enters the blood, and at the same time carbon dioxide moves from the blood to the alveoli. Respiratory function is noticeably impaired in inflammatory lung pathologies. Most often, patients are faced with unilateral infectious and inflammatory lesions. However, cases of bilateral lung damage are also common. This problem is especially relevant during periods of viral epidemics. In particular, this applies to swine flu (H1N1) and the new coronavirus infection COVID-19. In all patients with moderate, severe and extremely severe COVID-19, bilateral lung damage is observed.

The first, main feature of such a lesion, which should be noted, is that bilateral pneumonia is more severe than unilateral pneumonia. When a patient has one healthy lung, it fully copes with all the body’s needs to provide oxygen to organs and tissues. As a rule, the level of saturation (oxygen supply to tissues) with unilateral lesions is normal, which is not observed with bilateral pneumonia.

Like unilateral lung damage, bilateral pneumonia occurs in various morphological forms. The easiest to tolerate is focal pneumonia, in which the size of pneumonic infiltration (accumulation of immune cells and inflammatory elements in the lung) is no more than 2 cm. There are also segmental (damage within one segment of the lung), polysegmental (several segments of the lungs are involved) and lobar (affected lung lobe). As you might guess, the larger the affected area, the more severe the disease.

Bilateral pneumonia is especially severe in people over 65 years of age, children under 5 years of age, as well as in people with chronic diseases of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems and diabetes mellitus.

In both adults and children, bilateral interstitial pneumonia is the most severe. In this case, inflammation affects both the alveoli and perialveolar tissue. Thus, breathing function is significantly weakened.

Figure 1. Major respiratory organs. Source: Cancer Research UK / Wikimedia Commons

The condition of patients with interstitial pneumonia quickly deteriorates, leading to respiratory failure and requiring prompt medical intervention.

Important! Bilateral pneumonia and mechanical ventilation. Severe patients with bilateral lung damage can be transferred to artificial ventilation. This measure is resorted to when all other methods have not led to the desired result. Many people mistakenly believe that ventilators are the cause of the high mortality rate among patients on mechanical ventilation. However, the high mortality rate is primarily associated with the severity of the disease. Very severe patients with an initially high risk of death are transferred to mechanical ventilation. At the same time, when using mechanical ventilation, there are risks of lung injury, as well as infection with nosocomial infections.

University

→ Home → University → University in the media → Pneumonia: consider all risks

Pneumonia is an acute infectious and inflammatory process in the lungs, necessarily affecting the alveoli.

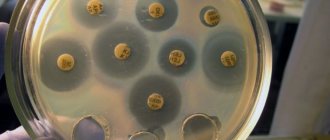

The range of microbial factors can be very wide, but a few predominate - Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Influenza, parainfluenza, adeno- and metapneumo-, and respiratory syncytial viruses lead to the development of pneumonia. Let's not get confused about the diagnosis

Methods of penetration of the pathogen into the lungs:

- aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions into the respiratory tract;

- inhalation of aerosol containing microorganisms;

- hematogenous;

- contagious.

Only the first two are the main ones. In the development of pneumonia, mechanical protective factors (aerodynamic filtration, bronchial branching, epiglottis, coughing and sneezing, mucociliary clearance), as well as cellular humoral mechanisms of nonspecific and specific immunity, are important. An imbalance between aggression and defense appears to be the impetus for the onset of the inflammatory process in the lungs.

There is a stable division of pneumonia into 2 groups: out-of-hospital and intra-hospital (hospital-acquired, nosocomial). Diagnosis of the classic form does not cause any particular difficulties: acute onset, cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, fever, local wheezing in the lungs - even an inexperienced doctor will suspect the disease and prescribe an X-ray examination. Changes on the radiograph (infiltration in the lung tissue) confirm the diagnosis. Recently, pneumonia with few symptoms and even asymptomatic cases has become common, which requires special attention from a doctor to rule out tuberculosis and lung cancer.

Case from practice. Patient M., 42 years old. I went to the clinic with complaints of general malaise and sweating. The medical history is unremarkable. Physical examination revealed no changes. General blood and urine tests are normal. X-ray examination of the chest organs revealed segmental infiltration in the lower lobe of the right lung (S6). With a diagnosis of pneumonia, M. was sent to the hospital. The absence of clear clinical manifestations and changes in laboratory data raised doubts about the correctness of the diagnosis, however, even after additional examination (sputum analysis for AFB, computed tomography of the chest) no other diseases were detected. The issue was resolved by a course of standard antibacterial therapy: as a result, the patient’s state of health returned to normal, and the infiltration on the chest X-ray disappeared.

Case from practice. Patient Z., 53 years old. When performing annual fluorography, a darkening was detected in the lower lobe of the left lung. The patient was sent to the clinic with a diagnosis of left-sided lower lobe pneumonia. There are no complaints upon examination. He has been smoking for over 30 years. Works as a driver. In the lungs, upon auscultation on the left, breathing is weakened. Percussion sound over the lungs is not changed. ESR increased to 35 mm/hour. The chest X-ray shows extensive darkening in the lower lobe of the left lung. The discrepancy between the clinical and anamnestic data and the typical X-ray picture became the basis for bronchoscopy - an exophytically growing tumor was detected in the lower lobe bronchus on the left with obstruction of the lumen. Histological examination revealed small cell lung cancer.

A wide range of disorders can be hidden under inflammation: pulmonary embolism, heart pathology, systemic diseases of connective tissue, blood, etc. The clinical picture has features in various forms of pneumonia (lobar and focal). The first is characterized by a violent onset with maximum severity of symptoms. Focal (bronchopneumonia) often develops gradually, layering on ARVI.

For diagnosis from laboratory tests, first of all, a general blood test is necessary (leukocytosis, shift of the formula to the left, increase in ESR). After clarifying the diagnosis, it is important to assess the severity of the disease, the presence of complications or foresee their possible risk. Currently, two gradations are allowed: severe and non-severe pneumonia. As for complications, the list is impressive; some are very pronounced and threaten the patient’s life (septic shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome), others can only be determined by special research methods, but are also very serious.

The tactics for examining and treating patients with pneumonia are selected on the basis of clinical protocols approved by the Ministry of Health; new ones have been in effect since 2012 (Order of the Ministry of Health dated July 5, 2012 No. 768).

The doctor inevitably faces the question of the place of treatment: outpatient or inpatient? Patients with severe pneumonia require hospitalization. According to clinical protocols, “minor” and “major” criteria for severe “pneumonia” are distinguished.

"Big" criteria:

- need for artificial ventilation;

- rapid progression of focal infiltrative changes - an increase in the size of infiltration over 50% within 2 days;

- septic shock, the need to administer vasopressor drugs for 4 hours or more;

- acute renal failure (urine volume less than 80 ml in 4 hours, serum creatinine level greater than 0.18 mmol/L, or urea nitrogen concentration greater than 7 mmol/L

- in the absence of chronic renal failure).

"Small" criteria:

- respiratory rate (30 per 1 minute or more);

- disturbance of consciousness;

- SaO2 less than 90% (according to pulse oximetry);

- partial tension of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) is less than 60 mm Hg. Art.;

- systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg. Art.;

- bilateral or multifocal lung damage;

- decay cavities, pleural effusion.

Severe pneumonia is diagnosed when the patient has two “minor” or one “major” criteria, each of which significantly increases the risk of death. In such cases, we are talking about emergency hospitalization in the intensive care unit. A doctor who does not have the opportunity to examine the patient (outpatient stage) needs to pay attention to two points: shortness of breath (at rest or with minimal exertion) and a decrease in blood pressure. When these signs are present, you need to take the person to a medical facility as soon as possible.

- Pneumonia may not be severe, but it is still preferable to hospitalize patients in the following cases:

- age over 60 years;

- concomitant diseases (chronic bronchitis, COPD, bronchiectasis, malignant neoplasms, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal and congestive heart failure, chronic alcoholism, drug addiction, severe underweight, cerebrovascular pathology);

- ineffectiveness of initial antibiotic therapy;

- pregnancy.

The decision to hospitalize is influenced by the lack of adequate care and compliance with all medical prescriptions at home, as well as the desire of the patient and/or his family members.

We select the antibiotic empirically

Antibacterial therapy is the main thing in the treatment of pneumonia. Successful administration of the drug almost always determines a favorable outcome. Unfortunately, the problem of timely and accurate etiological diagnosis remains unresolved. Therefore, as before, the empirical approach remains. The choice of antibiotic is influenced by the severity of pneumonia, the person’s age, concomitant diseases, and a number of other factors.

According to clinical protocols, if this is an outpatient patient under 60 years of age with mild pneumonia, without concomitant pathology, then the antibiotics of choice are amoxicillin and/or oral macrolides. In patients over 60 years of age and/or with concomitant diseases - amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; macrolides: azithromycin or clarithromycin orally. Assessment of the effectiveness of antibacterial therapy - after 48–72 hours (decrease in temperature to normal or subfebrile, improvement in general well-being). When the initial course has no effect, hospitalization is necessary.

Case from practice. Patient K., 27 years old. He went to the clinic with complaints of a dry cough and fever up to 38 °C. There are moist rales in the lower lobe of the right lung upon auscultation; acute phase indicators are increased; According to X-ray examination, there is infiltration in the lower lobe on the right. Community-acquired pneumonia was diagnosed in the lower lobe on the right. K. refused hospitalization due to family reasons. Since the pneumonia is not severe, the following was prescribed on an outpatient basis: amoxicillin 0.5, 1 capsule 3 times a day, acetylcysteine, antipyretics, and plenty of fluids. On the third day there were no positive dynamics: fever, cough; Moreover, shortness of breath began to appear when moving. The patient was again strongly recommended to be hospitalized, and this time he agreed. Subsequent inpatient treatment was successful.

For the treatment of moderate pneumonia in a hospital, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid is prescribed intravenously in combination with azithromycin or clarithromycin, or 3rd generation cephalosporins intramuscularly or intravenously in combination with azithromycin. Reserve antibiotics: carbapenems, cefoperazone/sulbactam, respiratory fluoroquinolones. For severe pneumonia, antibiotics of choice: cefotaxime or ceftriaxone - IV + azithromycin IV or clarithromycin, or carbapenems (meropenem, doripenem, ertapenem or imipenem/cilastatin). If P. aeruginosa infection is suspected, cefepime, imipenem/cilastatin, meropenem, doripenem, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, cefoperazone/sulbactam, ceftazidime should be preferred. When therapy is ineffective, there is a suspicion of MRSA infection, linezolid, or teicoplanin, or vancomycin is prescribed. Mucoregulation, anti-inflammatory therapy, detoxification, and physiotherapeutic methods are also used.

Case from practice. Patient N., 43 years old. Delivered to the hospital in a state of alcoholic intoxication. Picked up on the street by an ambulance crew. The condition upon examination is serious. Consciousness is impaired, stupor. The smell of alcohol. Body temperature 37.8 °C. The skin is gray, facial hyperemia. Blood pressure 100/60 mm Hg. Art. Heart sounds are dull and rhythmic. Respiration rate - 30/min. On auscultation in the lower parts of the lungs there are moist fine bubbling rales. The stomach is soft. The chest x-ray shows massive subtotal infiltration on the right, an area of infiltration on the left in the middle pulmonary field. In the general blood test, leukocytosis is up to 30109/l, the formula shifts to the left (20% of band forms). Oxygen saturation 78%. With a diagnosis of “community-acquired bilateral pneumonia (subtotal on the right), severe course. ADN2” patient was admitted to the ICU. Antibacterial therapy was prescribed (meropenem 2.0 IV after 8 hours + Klacid 0.5 IV after 12 hours) against the background of complex therapy to support hemodynamics, detoxification, mucoregulation, oxygen therapy. Over the next 2 days, the patient's condition did not change. She was not present at the X-ray examination either. It was decided to add levofloxacin to the treatment. After another 2 days, 2 areas of destruction appeared on the chest X-ray in the middle pulmonary field on the right. Considering the negative dynamics on the x-ray, the high probability of staphylococcal infection, and in particular MRSA (which was later confirmed by sputum examination), the doctor prescribed teicoplanin 400 mg IV instead of Klacid. The latest therapy adjustment had a positive effect on the dynamics: the temperature returned to normal, the general condition improved; the patient was transferred to the pulmonology department, where treatment was successfully continued.

In clinical practice, there are special variants of pneumonia that deserve separate presentation: hospital-acquired, viral, aspiration, as well as pneumonia in patients with immunodeficiency.

The material is intended for pulmonologists, therapists, and general practitioners. Valery Grib , Associate Professor of the 1st Department of Internal Diseases of the Belarusian State Medical University, Candidate of Medical Sciences. Sciences Medical Bulletin , September 26, 2013

Share

Causes of development of bilateral pneumonia

The most common cause of bilateral pneumonia is an infection in the lungs. Most often these are the following types of infectious pathogens:

- Bacteria. As a rule, these are pneumonia caused by streptococci, pneumococci, staphylococci and other types of bacterial pathogens. In medical practice, bacterial pneumonia occurs most often. A serious problem is nosocomial infections that affect the patient's respiratory system during aspiration, ventilation, surgery, or taking cytotoxic drugs.

- Viruses. Viral pneumonias are less common than bacterial ones. Most often, pneumonia is caused by influenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, and coronaviruses (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV). With a viral infection, the interstitial tissues of the lungs often become inflamed with the formation of infiltrates in the alveolar sacs. Damage occurs as a result of the immune response to infection. During a viral infection, white blood cells (in particular, lymphocytes) activate cytokines (the so-called cytokine storm), which leads to the accumulation of fluid in the alveoli and further respiratory failure.

- Fungi. Fungal pneumonias are much less common than bacterial or viral ones. Often, fungal infection of the lungs is observed against the background of intensive antibacterial therapy. Pneumonia caused by fungi also occurs in people with weakened immune systems (eg, HIV-infected patients), as well as patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Source: PheelingsMedia / Depositphotos

It is noteworthy that the likelihood of developing bilateral pneumonia in some categories of people is higher than in others. Let's consider the main risk factors for the development of bilateral pneumonia:

- Age – people over 65 and children under 5 years old.

- Lack of vitamins and nutrients (people with morbid thinness).

- Pulmonary diseases, such as asthma, COPD, cystic fibrosis, tuberculosis and others.

- Smoking.

- Presence of chronic diseases. In particular, these are heart and vascular diseases, lung pathologies, and diabetes.

- Immune system dysfunction. It is noteworthy that the danger lies in both a weakened immune system and a hyperimmune response. People suffering from autoimmune diseases are also at risk.

- Patients taking immunosuppressants—drugs that suppress the immune system.

- People who have problems swallowing.

- People who have recently had a viral or bacterial respiratory tract infection.

General information

According to statistics, in Russia pathology is recorded:

- in preschool children – up to 500 cases per 100 thousand people;

- in adults up to 800 cases per 100 thousand people.

Polysegmental pneumonia is a multicomponent disease that develops due to infection of the body by harmful microorganisms (fungi, viruses, parasites, bacteria) against the background of a sharp decrease in immunity.

Typical side processes affect the lymph nodes and provoke oxygen and heart failure. Due to anatomical features, the right lung in segments II, VI, X and the left lung in VI, VIII, IX, X are most often affected.

80% of patients do not require hospitalization, 20% are treated in a hospital department, patients with an aggressive course of the disease are admitted to intensive care, and the mortality rate is 5%.

Symptoms

It is impossible to determine whether a person has unilateral or bilateral pneumonia based on external signs. For example, it is not uncommon for a patient with COVID-19 to have seemingly normal breathing and only have a high fever, but a computed tomography (CT) scan reveals bilateral pneumonia.

Some signs of diseases that usually cause pneumonia may indicate the possibility of pneumonia. These symptoms include:

- High fever, often accompanied by chills and shaking. However, it may also be a low-grade fever (not higher than 38 degrees Celsius). In very rare cases, with pneumonia, the patient experiences a decrease in temperature (as a rule, this symptom rarely occurs in elderly patients).

- Dry cough that gets worse over time. Over time, thick mucus or phlegm may be discharged.

- Shortness of breath at rest or when performing physical work that has not previously caused shortness of breath. This symptom indicates partial respiratory failure.

- Chest pain when coughing or breathing.

- Severe malaise, weakness.

- Nausea and vomiting are observed in rare cases.

In people over 65 years of age, pneumonia (either unilateral or bilateral) can lead to confusion and changes in thinking.

When to see a doctor

There are no specific symptoms for bilateral pneumonia. Most often, the symptoms resemble a cold or flu, and with such symptoms people prefer to be treated at home. However, at present, when there is a high probability of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, if such symptoms occur, it is advisable to consult a doctor and undergo appropriate diagnostics.

You should also contact your doctor if you have difficulty breathing or if you experience chest pain when coughing or breathing. Remember, the sooner you see a doctor, the higher the chances of successful treatment of pneumonia.

Figure 2: Bilateral pneumonia on an x-ray in two projections. Source: PHIL CDC

Management of patients with CAP in outpatient settings

For mild pneumonia, antibacterial treatment of adults and children can be completed with stable normalization of body temperature for 3–4 days (total course duration 7–10 days). If there is clinical/epidemiological evidence of mycoplasma or chlamydial infection, the duration of therapy should be 14 days. An initial assessment of the effectiveness of therapy should be carried out 48–72 hours after the end of the course of treatment (re-examination). If symptoms persist or progress, it is necessary to reconsider the tactics of antibacterial therapy and re-evaluate the advisability of hospitalization.

According to the recommendations of the Russian Respiratory Society, outpatient patients are divided into 2 groups, differing in etiological structure and tactics of antibacterial therapy (see Table 1. Antibacterial therapy of CAP in outpatients):

Table 1.

Antibacterial therapy of CAP in outpatients

| Group | Most common pathogens | Drugs of choice | Alternative drugs | Patient characteristics |

| Mild CAP in patients under 60 years of age without concomitant pathology | S. pneumoniae M. pneumoniae C. pneumoniae H. influenzae | Amoxicillin orally or macrolides (azithromycin, clarithromycin) orally | Respiratory fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin, moxifloxacin) orally | |

| Mild CAP in patients over 60 years of age and/or with signs of concomitant pathology | S. pneumoniae C. pneumoniae H. influenzae S. aureus Enterobacteriaceae | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid or Amoxicillin + sulbactam orally | Respiratory fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin, moxifloxacin) orally | Concomitant diseases affecting etiology and prognosis: COPD, diabetes, congestive heart failure, liver cirrhosis, alcohol abuse, drug addiction, exhaustion |

Diagnostics

The diagnostic protocol for suspected pneumonia usually includes the following procedures:

- Blood tests (general, biochemical). The blood formula, the level of C-reactive protein and a number of other markers of the infectious and inflammatory process are determined.

- X-ray of the lungs - allows you to identify the source of inflammation.

- Computed tomography - prescribed in cases where radiography does not show lung damage, but the clinical picture indicates the opposite. Computed tomography can detect ground-glass lesions in the lungs. These are changes in the lung tissue at the level of the alveoli. This type of inflammation is often noted with viral pneumonia, for example, with influenza or coronavirus infection.

- Pulse oximetry – measuring the level of oxygen in the blood (saturation).

- Sputum analysis. A sputum sample is taken from the patient and a bacteriological examination or PCR analysis is performed to determine the causative agent of the infection.

Treatment

Treatment of both unilateral and bilateral pneumonia is aimed at eliminating the infectious process and preventing complications. The treatment algorithm depends on both the pathogen and the clinical picture of the disease.

To make breathing easier, drugs that dilate the bronchi are used. Compensation for respiratory failure is carried out through oxygen therapy. Hormonal anti-inflammatory drugs (corticosteroids) are used to suppress inflammation and cytokine storm. The latter have proven themselves well in the treatment of pneumonia caused by coronavirus infection.

Figure 3. Ventilator. It is usually prescribed for severe cases of pneumonia. Source: Maxim Mishin / Moscow Government

As for antiviral drugs for viral pneumonia, they are not always used. In this case, it all depends on the type of virus. Currently, only a few antiviral drugs with proven effectiveness against influenza viruses are available to medicine. In other cases, the use of these means makes no sense.

Separately, it is necessary to say about antibiotics. They are prescribed only by a doctor if the bacterial origin of pneumonia is proven. Antibiotics are also appropriate if there is a high risk of bacterial complications due to a viral infection. All these risks, as well as the timing of taking the drug, are determined by the doctor after diagnosis. Self-administration of antibacterial drugs is unacceptable.

Management of patients with CAP in a hospital setting

It is advisable to begin therapy for pneumonia in hospitalized patients with parenteral antibiotics. After 3–4 days, provided the temperature normalizes, intoxication and other symptoms decrease, it is possible to switch to oral forms of antibiotics until the course of treatment is completed (step-down therapy). Antibacterial drugs can be used both as part of combination therapy and as monotherapy. More detailed treatment regimens for CAP are presented in Table No. 2.

Table 2.

Treatment regimens for CAP depending on the course

| Group | Most common pathogens | Recommended treatment regimens | |

| Drugs of choice | Alternative drugs | ||

| EP of non-severe course | S. pneumoniae H. influenzae C. pneumoniae S. aureus Enterobacteriaceae | Benzylpenicillin IV, IM ± macrolide (clarithromycin, azithromycin) orally, or Ampicillin IV, IM ± macrolide orally, or Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid IV ± macrolide orally, or Cefuroxime IV, IV m ± macrolide orally, or Cefotaxime IV, IM ± macrolide orally, or Ceftriaxone IV, IM ± macrolide orally | Respiratory fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin, moxifloxacin) IV Azithromycin IV |

| Severe EP | S. pneumoniae Legionella spp. S. aureus Enterobacteriaceae | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid IV + macrolide IV, or Cefotaxime IV + macrolide IV, or Ceftriaxone IV + macrolide IV | Respiratory fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin, moxifloxacin) IV + III generation cephalosporins IV |

Note:

- If the presence of “atypical” pneumonia is suspected, the use of macrolides is indicated.

- If there is a risk of infection with P. aeruginosa (bronchiectasis, use of corticosteroids, therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics for more than 7 days during the last month, exhaustion), the drugs of choice are ceftazidime, cefepime, cefoperazone + sulbactam, meropenem, imipenem, piperacillin/tazobactam, ciprofloxacin, in monotherapy or in combination with aminoglycosides of the II–III generation.

- If aspiration is suspected, the following treatment options are indicated: cefoperazone + sulbactam, ticarcillin + clavulanic acid, carbapenems, piperacillin/tazobactam.

An initial assessment of the effectiveness of antibacterial therapy should be carried out 24–48 hours after the start of treatment. If signs of pneumonia persist in adults or children, treatment tactics should be reconsidered.

For mild CAP, the course of antibiotic therapy is about 7–10 days. For severe CAP of unspecified etiology, a 10-day course of antibiotic therapy is recommended. If there is evidence of mycoplasma or chlamydial etiology, therapy should last 14 days; in the case of CAP caused by staphylococci, gram-negative enterobacteria, legionella, the duration of therapy is 14–21 days.

In addition to antibiotics, the following are used in the treatment of CAP:

- Antiviral therapy: neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir, zanamivir), active against influenza A and B viruses. Duration of use is 5–10 days.

- Mucolytics and expectorants - tablet or inhalation forms.

- Glucocorticosteroids: used for developed septic shock (hydrocortisone 200–300 mg/day for no more than 7 days).

- Oxygen therapy for PaO2 < 55 mm Hg. Art. or SpO2 < 88% (breathing air). It is optimal to maintain SpO2 within 88–95% or PaO2 within 55–80 mm Hg. Art.

- Infusion therapy - to correct hypovolemia.

- Low molecular weight heparins for the prevention of thromboembolism in severe patients.

- Physiotherapy and exercise therapy to reduce inflammation and improve sputum discharge.