Causes of epilepsy in children

Before starting treatment, the doctor first identifies the causes of epilepsy in children. Today there are several main factors.

- Hereditary disease. A special substance, dopamine, the level of which is programmed in genes, is responsible for stopping overly excited neurons. Accordingly, if the parents of a sick child have ever suffered or are currently suffering from epilepsy, then it is likely that he received this pathology from them.

- Intrauterine brain malformation. In most cases, such causes of epilepsy in children arise due to their mother’s abuse of alcohol, cigarettes, and medications prohibited for use during pregnancy. Also, these defects can occur in primiparous, middle-aged women, the state of their health during pregnancy.

- Injuries received during childbirth. Seizures of epilepsy in children can occur due to injuries received from the midwife's forceps, the procedure for vacuum extraction of the baby, prolonged labor, or compression of the baby's neck by the umbilical cord.

- Inflammatory brain diseases. This includes meningitis, encephalitis and others.

- Increased body temperature due to a cold or viral disease. As a rule, seizures for this reason appear in children with not very healthy heredity.

In addition to the above, the following factors may also be observed:

- traumatic brain injuries. The cause of epilepsy in children who have received serious blows to the head is quite common;

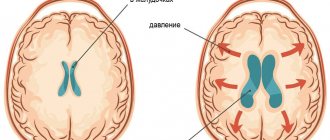

- tumor neoplasms. The grown tumor puts serious pressure on the child’s fragile brain, which provokes the appearance of epileptic seizures;

- disruptions in metabolism in the body. This should include hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia and others;

- problems with cerebral blood flow;

- abuse of narcotic and serious medications. This reason is most relevant for children experiencing adolescence.

Treatment

Neurologists at the Yusupov Hospital provide complex treatment for epilepsy. It is aimed at reducing the frequency of epileptic seizures and stopping medications during remission. According to statistics, in 70% of cases, adequately selected treatment helps to almost completely relieve paroxysmal activity in patients.

To achieve optimal results in treatment, patients are prescribed drugs for epilepsy of the following properties:

- anticonvulsants – help relax muscles, they are prescribed to both adults and children;

- tranquilizers - allow you to remove or reduce the excitability of nerve fibers; the drugs have shown a high degree of effectiveness in the fight against minor attacks;

- sedatives – help relieve nervous tension and prevent the development of severe depressive disorders;

- injections - used for twilight states and affective disorders.

Idiopathic focal epilepsy is benign. It requires symptomatic treatment. In focal forms with seizures that appear in series 2-3 times a month and are accompanied by an increase in mental disorders, neurosurgeons perform surgery.

Symptoms of epilepsy in children

The signs of epilepsy in children are generally similar, but may differ depending on the age at which the child is at this stage.

Manifestation of epilepsy in infants

It is extremely important to detect and begin timely treatment of the first signs of epilepsy in a child of the first year of life: at this stage, while all processes are maturing, they can be adjusted as easily as possible. However, this also has its own difficulty: the signs of epilepsy in children under one year of age are very different from those in older age.

Symptoms include the following:

- sudden freezing without movement;

- suspension of swallowing;

- tilting the head back;

- eyelid tremor;

- a gaze directed into emptiness, not noticing anything or anyone;

- lack of response to the actions of parents.

In most cases, the listed symptoms begin an attack, after which the baby loses consciousness and convulsions appear. In the process, he may unknowingly perform an act of defecation or void himself.

Symptoms of epilepsy in children after one year

Epilepsy in children after one year manifests itself a little differently:

- temporary loss of consciousness;

- motor activity disorders;

- problems with sensory perception;

- a sharp change in mood, especially towards increased aggression;

- numbness of some parts of the body.

These signs of epilepsy in children are not always noticeable, but should alert parents. If you do nothing, then the following will appear after them:

- brief cessation of breathing;

- strong tone of all muscles at the same time;

- convulsions;

- uncontrolled urination, defecation;

- often biting the tongue, screaming.

Epilepsy in children is often accompanied by chronic depression and moral depression.

Forms of epilepsy in children

Depending on what triggered epilepsy attacks in children, there are three main forms:

- idiopathic: manifestations of the disease do not entail significant changes in brain function and have a genetic basis;

- symptomatic: arose as a result of brain pathology caused by a tumor, injury or malformation;

- cryptogenic: the exact cause of epilepsy in children is not clear.

Types of epilepsy

When diagnosing epilepsy in children, the location of the source of the disease is also taken into account. Depending on this, the disease is divided into several types:

- occipital;

- parietal;

- frontal (activated at night);

- temporal (loss of consciousness without characteristic convulsions);

- chronic.

There is another classification based on what caused epilepsy in children under one year of age and later:

- primary: appeared due to excessive brain activity;

- secondary: caused by injury or infectious disease;

- reflex: any stimulus can act as a provocateur, for example, a flashing lamp, any sound.

Diagnostics

If you suspect small, insignificant attacks, manifested in the form of short-term freezing or sleepwalking at night, you need to contact a pediatrician, neurologist and conduct a thorough study, since such symptoms are characteristic of a number of diseases.

There is only one way to prove that a patient has epilepsy - EEG (electroencephalography). The results of the study will show specific abnormalities in the functioning of neurons leading to seizures.

When the diagnosis of a seizure disorder is confirmed, the neurologist prescribes additional studies. This is necessary to find out the location and number of foci, the systematic nature of their awakening:

- computed tomography (CT);

- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI);

- video-EEG monitoring.

After studying the results of the study, the type of pathology is specified and complex treatment is prescribed.

When to see a doctor?

Only an epileptologist knows exactly how epilepsy manifests itself in children, can determine its type and prescribe adequate treatment.

Therefore, if you notice the first sign of epilepsy in a child, immediately contact a competent specialist. The earlier he diagnoses the disease, the faster and easier the therapeutic process can be.

The pediatric department of JSC “Medicine” (clinic of academician Roitberg) employs specialists who have many years of practice behind them and work with the most difficult situations.

The building, equipped with the latest specialized technology, is located in the center of Moscow, at 2nd Tverskoy-Yamskaya lane, building 10. Just a 5-minute walk away are the Mayakovskaya, Tverskaya, Chekhovskaya, and Novoslobodskaya metro stations. . You can make an appointment for your child by calling +7 (495) 995-00-33 or using the feedback form.

The following types of attacks are distinguished:

- Generalized convulsive seizures consist of sudden muscle tension and short-term cessation of breathing. Then convulsions begin, lasting from 10 seconds to 20 minutes. The attack stops on its own, after which the child falls asleep.

- Nonconvulsive generalized seizures (absences) are less pronounced. They consist of sudden freezing, the patient’s gaze becomes absent. Sometimes the child's eyelids may tremble and his eyes may close. Duration is about 5-20 seconds; in the acute period, the child does not react to external stimuli. Once finished, he can continue to do his own thing. Typically, childhood epilepsy of this type begins at the age of 5-7 years and is more common in girls. After puberty, a child may “outgrow” the disease. But you shouldn’t wait for this, since the absence form can develop into a more complex one.

- Atonic attacks are characterized by sudden loss of consciousness with muscle relaxation. They are easily confused with fainting. If seizures occur frequently, this is a serious reason to contact a neurologist and pediatric epileptologist.

- Infantile spasm is an involuntary tilt of the head or torso forward with hands pressed to the chest. Seizures can occur after waking up, especially abruptly, and are typical for children under 3 years of age. By the age of five, childhood epilepsy of this type can either go away completely or change into another form.

In addition to the types described, there are other forms. If there is something alarming about your child’s condition, you should seek advice from a pediatric epileptologist.

Diagnosis of epilepsy in children

The primary diagnosis of epilepsy in children occurs using a special device - an electroencephalograph. Then a series of functional tests is mandatory, during which the vast majority of patients demonstrate manifestations of the disease.

At the discretion of the epileptologist, neuroimaging can be performed - a technique that demonstrates the exact location and characteristics of brain damage.

Additional, but no less informative methods include:

- CT, MRI;

- general analysis of urine and blood;

- analysis to determine the level of immunoglobulins, albumin, calcium, glucose, magnesium, iron and other elements;

- Dopplerography of cerebral vessels;

- determination of the qualitative state of the cerebrospinal fluid.

Is epilepsy curable?

Before starting treatment, a diagnosis should be determined, because loss of consciousness and various convulsions can occur due to a sharp drop in blood sugar, anemia, poisoning, high fever, cerebrovascular accident, calcium deficiency and other conditions. Antiepileptic drugs cannot be prescribed to such patients immediately. The diagnosis of epilepsy is made only when epileptic seizures recur.

The percentage of patients with epileptic seizures could be significantly lower if patients took medications regularly and did not stop treatment on their own. The decision to discontinue medications can only be made by a doctor, and not earlier than after 5 years of treatment, if during this time the patient has not had epileptic seizures. At the Yusupov Hospital, an epileptologist always monitors how the patient’s illness develops.

Treatment of epilepsy

Treatment of epilepsy in children is primarily aimed at restoring their normal well-being and reducing the frequency of attacks. Then, with the help of well-chosen therapy, the specialist minimizes them and, if possible, completely eliminates them, while simultaneously eliminating the cause of the disease.

Therapy is carried out in a complex and may include:

- drug treatment;

- dietary nutrition (focus on fats and reduction in carbohydrates);

- neurosurgical intervention;

- psychotherapeutic support.

There is no single plan according to which therapy is carried out. Much in the scheme depends on the specific form of the disease that the child suffers from, as well as the cause that caused it.

It is extremely important that the work of the epileptologist, the young patient and his parents is carried out together; the speed and quality of treatment depends on this. It is necessary to thoroughly follow all prescribed recommendations and establish a clear daily routine for the child.

Features of epilepsy in childhood

4. Features of epilepsy in childhood

The main features of childhood epilepsy are as follows:

- there is a large number of treatment-resistant forms of epilepsy;

- characteristic is a large polymorphism of epileptic paroxysms;

- the frequency of masked manifestations of the disease is high: behind many unclear pain attacks, umbilical colic, fainting, acetonemic vomiting, epileptic paroxysms of an organic nature may be hidden;

- Various non-epileptic phenomena, such as sleepwalking, night terrors, enuresis, migraines, syncope, and hysterical (conversion) seizures, are often mistaken for manifestations of epilepsy. At the same time, there is a tendency to regard similar and some other symptoms as epileptic in blood relatives of patients, using the term “diseases of the epileptic circle” to designate them. It should be taken into account that with any multifactorial disease, which includes epilepsy, many paroxysmal disorders of a non-epileptic nature can be found in the patient himself and his blood relatives. Therefore, at present, the terms “pre-epilepsy” and “diseases of the epileptic circle” are considered obsolete;

- in childhood epilepsy, a malignant course is often observed with the development of psychopathological symptoms and mental retardation;

- at the same time, in childhood, absolutely benign forms of epilepsy occur, ending with complete recovery, restoration of all body functions and successful socialization;

- In children there are also delayed forms of epilepsy, when seizures begin during the neonatal period, then they stop and then resume years later.

As for epileptic seizures, they have some common features in children:

- high frequency of undeveloped, incomplete, rudimentary forms of epiparoxysms;

- the presence of forms of epilepsy and types of seizures that do not occur in adult patients;

- high proportion of all absence forms of paroxysms;

- transformation of seizures as one gets older;

- frequent development of post-ictal focal neurological symptoms.

4.1. Epileptic syndromes in neonatal and infancy:

- benign idiopathic neonatal seizures. Appear around the 5th day. Have a favorable prognosis;

- benign idiopathic neonatal familial seizures. Occurs on the 2nd–3rd day of life. Someone in the family sometimes experiences the same cramps. The prognosis is favorable;

- early (neonatal) myoclonic encephalopathy: massive partial or fragmented myoclonus and partial motor seizures, short-term tonic seizures, spike fast-wave and slow-wave activity on the EEG. These signs indicate severe brain damage. Early death is common;

- early epileptic encephalopathy with the EEG phenomenon “suppression - discharges” - Ohtahara syndrome. Onset in the 1st month of life. Seizures are in the form of tonic ones, often grouped in a series of spasms. The EEG records alternating short periods of flattening of the curve and generalized epileptic activity. The prognosis is severe, and early death often occurs.

4.2. Epileptic syndromes of early childhood. These include the following.

1) Febrile convulsions (see paragraph 2.6).

2) Benign myoclonic epilepsy of early childhood. The earliest form of idiopathic epilepsy. Onset in the 1st–2nd year of life in children with normal development. Seizures in the form of generalized myoclonus. EEG shows spike-wave activity during slow-wave sleep. The prognosis is good. The treatment of choice is valproate.

3) Severe myoclonic epilepsy. One of the most malignant forms, absolutely resistant to therapy. Onset in the 1st year of life in healthy children with a family history of epilepsy and febrile seizures. Characterized by febrile unilateral clonic seizures, myoclonus, and often partial seizures. Generalized spike waves and polyspike waves are recorded on the EEG. There is a pronounced delay in mental development and severe neurological symptoms.

4) Myoclonic epilepsy (myoclonic status) in combination with non-progressive encephalopathy. Encephalopathy is detected from the first months of life in the form of an atonic variant of cerebral palsy, dyskinetic syndrome and severe mental retardation. Myoclonus varies from rhythmic bilateral to asynchronous. Polysomnographic studies during slow-wave sleep show an EEG picture of status epilepticus. Encephalopathy does not progress. Over time, the condition stabilizes, although myoclonus persists and absence seizures occur.

4.3. Childhood and adolescent forms of epilepsy.

1) Childhood absence epilepsy, or Friedman's syndrome (1906), pycnolepsy, pycnoepilepsy (Greek pyknos - frequent; lepsis - attack, grasping). Usually begins in children aged 6–7 years (according to other sources, at 4–10 or 2–8 years). It is more common in girls and is characterized by a high degree of hereditary predisposition (penetrance of the epilepsy gene). The main symptom of the disease is the presence of typical absence seizures, which in most cases occur with a tonic component and are retropulsive (the head falls back, the eyes rise up). It is noted that retropulsive seizures are often accompanied by a mild clonic component - twitching of the muscles of the face and eyelids. The frequency of seizures can reach dozens per day, absence seizure status is also observed. Focal postictal neurological symptoms, mental retardation and neurodestructive changes in the brain are not detected. The disease responds well to therapy. The treatment of choice is valproate, if necessary in combination with succinimides.

2) Juvenile absence epilepsy is an age-dependent form of idiopathic epilepsy. Begins at puberty, there are no differences in sexual preference. It manifests itself as a combination of simple absence seizures and primarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Seizures appear much less frequently, and their duration is longer than with pycnolepsy. The EEG shows paroxysms of generalized, synchronous, symmetrical spike waves with a frequency of 3.5–4 Hz. Responds well to therapy. The treatment of choice is valproate.

3) Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, or impulsive Janz epilepsy. Age-dependent form of idiopathic epilepsy. It begins in adolescents aged 12–16 years, and is more common in girls. A hereditary predisposition is noted, the disease gene is mapped to the 6p21.3 locus. It manifests itself as generalized myoclonic seizures, mainly after sleep, and occurs in the form of sudden symmetrical or asymmetrical twitching in the muscles of the shoulder girdle - flinching of one or both arms (“wing flapping”). At the same time, the arms involuntarily fall to the side, objects fall out of the hands, the head and torso turn sharply. Often, the muscles of the pelvic girdle and legs are involved in a myoclonic attack - the patient may squat at this time, fall on his knees or buttocks (myoclonic-astatic attack). Seizures occur in series or in bursts of 5–20 times in a row over several hours. On the EEG during an attack, in response to photostimulation, generalized spike and polyspike waves are recorded, often with gigantic amplitude, both episodic and spontaneous. The most important factor in provoking seizures is sleep deprivation. Consciousness is not impaired during seizures. Characterized by the absence of pronounced neurological symptoms and intellectual impairment. Treatment requires the elimination of provoking factors and the use of valproate, sometimes in combination with clonazepam.

4) Epilepsy with generalized tonic-clonic seizures on awakening. The main role in the development of the disease is attributed to genetic factors, but it is believed that there may also be symptomatic forms. It begins at the age of 10–20 years, sometimes earlier and later. Seizures occur within 2 hours of waking up from sleep, regardless of whether it is at night or during the day. Seizures are usually preceded by a series of bilateral myoclonus. There may also be a second peak of attacks before bedtime, especially with late onset of the disease. The EEG is characterized by an increased number of slow waves and generalized spike-wave and polyspike-wave activity at a frequency of 2.5–4 Hz. The prognosis is favorable. The main treatment is valproate and phenobarbital.

5) West syndrome (West), or infantile spasm. These are symptomatic and cryptogenic forms of epilepsy. One of the most common age-dependent epileptic syndromes. May begin in infancy, with peak incidence occurring between 2–4 and 7 months of age, sometimes later. More common in boys.

In typical cases, West syndrome is characterized by a triad of symptoms: a) generalized myoclonic or myoclonic-tonic seizures; b) delayed mental, speech and motor development and c) hypsarrhythmia.

Seizures manifest themselves as:

- sudden sharp bending of the head (nodding);

- sudden sharp bending of the head and shoulders (peck);

- slow tonic bends with extension and abduction of the arms according to the type of eastern greeting (“Salaam convulsions”);

- sudden propulsive movements with falling forward. Seizures are accompanied by a scream, an expression of fear on the face, a grimace of a violent smile. Injuries due to falls during an attack are common.

The duration of attacks ranges from fractions to several seconds. Seizures can be single or occur in series, numbering several hundred attacks per day. Most often, seizures appear before bedtime, when falling asleep, but especially often in the morning - during awakening or immediately after waking up from sleep. There are “good” and “bad” days – with fewer and more frequent attacks.

On the EEG, a special type of disturbance is recorded in patients - hypsarrhythmia: the absence of main activity and the presence of asynchronous slow activity, which alternates with sharp waves or spikes. The prognosis is poor: as people get older, myoclonic and myoclonic-tonic seizures transform into grand mal seizures.

Therapy: ACTH or glucocorticoids in combination with valproate and benzodiazepines, large doses of pyridoxine (up to 100 mg/kg/day), in resistant cases immunoglobulin G IV.

6) Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. This is an age-related encephalopathy syndrome of unknown origin. The onset of the disease occurs between the ages of 1 and 8 years (according to other sources, from 3 to 6 years). Often this syndrome is transformed from a previous infantile spasm. In typical cases the following are observed:

- epileptic seizures mainly of the type of generalized tonic, atonic seizures and atypical absence seizures;

- severe delay in mental, speech and motor development;

- specific changes on the EEG.

Seizures most often occur in the morning, and there are “good” and “bad” days. Falls during seizures are often accompanied by injury. Tonic seizures are detected in 100% of patients. They last from 5 to 20 seconds and proceed according to the tonic-axial type (with rotation of the body around its axis). The EEG shows complexes of bilateral, synchronous spike waves of 1–2.5 Hz, irregular and unstable, transforming under the influence of sleep into rhythmic activity with a frequency of 10 Hz.

Subsequently, the seizures are replaced by generalized and complex partial seizures. In treatment, a combination of carbamazepine, valproate and benzodiazepines is used, in recent years - lamotrigine, vigabatrin, which are more effective in treating attacks of falling. The effectiveness of intravenous administration of immunoglobulin G has been established.

7) Duse syndrome, or myoclonic-astatic epilepsy. Symptomatic and cryptogenic form of the disease with age-dependent seizures. Begins in the 1st–2nd year of life with febrile and nonfebrile generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The main manifestation is myoclonic and astatic seizures. The EEG shows multifocal changes with generalized spike waves, spontaneous and in response to photostimulation. Spontaneous remissions are observed, but a malignant course is also possible. Treatment: Valproate is used, alone or in combination with ethosuximide, and sometimes with benzodiazepines. In the presence of generalized tonic-clonic seizures - ACTH, glucocorticoids. Carbamazepine is contraindicated.

Epilepsy with myoclonic absence seizures. Age-dependent form of symptomatic and cryptogenic epilepsy with onset at 6–8 years. It manifests itself as myoclonic absences lasting 10–60 seconds with massive bilateral rhythmic myoclonus. The EEG shows the rhythm of typical absence seizures with high photosensitivity. Most patients experience infrequent generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Subsequently, mental retardation is revealed. Treatment resistance is common. Therapy: use valproate, phenobarbital, clonazepam and other benzodiazepines.

Epilepsy with myoclonic absence seizures. Age-dependent form of symptomatic and cryptogenic epilepsy with onset at 6–8 years. It manifests itself as myoclonic absences lasting 10–60 seconds with massive bilateral rhythmic myoclonus. The EEG shows the rhythm of typical absence seizures with high photosensitivity. Most patients experience infrequent generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Subsequently, mental retardation is revealed. Treatment resistance is common. Therapy: use valproate, phenobarbital, clonazepam and other benzodiazepines.

In children, especially in prepubertal age, there are rare forms of epilepsy with myoclonus of the eyelids and “self-evoking epilepsy” with seizures sensitive to the closing and opening of the eyelids and light flickers.

9) Rolandic epilepsy, or benign epilepsy with centrotemporal adhesions. Hereditary complications play a major role in the etiology of the disease. Onset between ages 3 and 13 years. Convulsions or paresthesias during a seizure involve the face, lips, tongue, and pharynx. Possible speech arrest or anarthria. Drooling is common. Consciousness remains clear. Seizures can spread, becoming brachiofacial or even unilateral in nature. There may be, less frequently, attacks with throat sounds and loss of consciousness, with secondary generalization of seizures. EEG - biphasic high-voltage spikes, following at short intervals in the central and temporal regions, unilateral or bilateral with a predominance on one side. Adhesions sharply intensify in a state of drowsiness or sleep. Therapy: phenobarbital and carbamazepine. After the cessation of attacks and normalization of the EEG, even with short-term treatment (1–2 years), it can be stopped. For rare seizures, anticonvulsants may not be prescribed.

10) Benign partial epilepsy with affective symptoms. There is a high degree of hereditary burden. The onset of the disease is at the age of 2–10 years in children with normal development. Seizures are characterized by sudden fear (to the point of horror) in combination with chewing, swallowing, and vegetative symptoms (pallor, hyperhidrosis, abdominal pain, etc.). Consciousness is usually altered. On the EEG there are complexes of a sharp wave - a slow wave in the frontal or parietal region on one or both sides. Therapy: carbamazepine and phenytoin. The prognosis is favorable.

(Landau-Kleffner syndrome - see Chapter 2.)

Return to Contents

Causes of epilepsy

In 60% of cases, people suffering from epilepsy or parents of sick children never receive an answer to the question of why the attack occurred. In such cases, epilepsy is diagnosed as “idiopathic” or “cryptogenic”, that is, the cause of the disease is unknown.

If the cause of epilepsy is identified, it is classified as secondary (symptomatic) epilepsy. Seizures can be stopped by eliminating the root cause. Causes of secondary epilepsy include:

- Genetic predisposition to epilepsy

- Organic brain damage in the prenatal, natal period: hypoxia, fetal asphyxia (critical lack of oxygen), severe prematurity

- Aggravated obstetric history: trauma during childbirth - the child gets stuck in the birth canal; if labor is weak, stimulants, epidural anesthesia, forceps, vacuum are used, which is also a risk factor for the newborn.

- Congenital abnormalities of brain development (hydrocephalus, microcephaly, genetic malformations, etc.)

- An infectious disease suffered by the mother, contact with a sick child (whooping cough, rubella, cytomegalovirus, Zikka virus, etc.)

- An infectious disease suffered by a child, with complications in the form of meningitis, encephalitis, neurocysticercosis.

- Malignant and benign neoplasms in the brain (cysts, hematomas, cancerous tumors)

- Congenital metabolic diseases (metabolic disorders)

- External factors - complications after vaccination, toxic shock

- In 60% of cases, the cause remains unclear (idiopathic form)