Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic inflammatory liver disease characterized by the loss of the body's immunological tolerance to tissue antigens [1, 2].

For the first time, information about severe liver damage with severe jaundice and hyperproteinemia appeared in the 30–40s. XX century. In 1950, the Swedish doctor Jan Waldenström observed chronic hepatitis with jaundice, telangiectasia, increased ESR, and hypergammaglobulinemia in 6 young women. Hepatitis responded well to treatment with corticotropin [3]. Due to the similarity of laboratory changes with the picture of systemic lupus erythematosus (the presence of antinuclear antibodies in the serum, positive results of the LE test), one of the names of the pathology became “lupoid hepatitis”.

Currently, autoimmune hepatitis is defined as chronic, predominantly periportal hepatitis with lymphocytic-plasmacytic infiltration and stepwise necrosis (Fig. 1). Characteristic manifestations: hypergammaglobulinemia, the appearance of autoantibodies in the blood.

Classification

Depending on the type of autoantibodies, three types of disease are distinguished:

- Type 1 AIH is the most common and is characterized by the appearance in the blood of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and/or smooth muscle antibodies (SMA).

- In type 2 AIH, autoantibodies are formed to microsomal antigens of the liver and kidneys (anti-liver kidney microsomal type-1 antibodies, anti-LKM-1).

- Type 3 AIH is associated with the formation of autoantibodies to soluble liver antigen, liver and pancreas tissue (anti-soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas antibodies, anti-SLA/LP).

- Some authors combine AIH 1 and AIH 3 due to the similarity of clinical and epidemiological features [4]. There are also crossover forms (overlap syndrome) of various autoimmune liver pathologies, including AIH: AIH + PBC (primary biliary cirrhosis), AIH + PSC ( primary sclerosing cholangitis). It is not yet entirely clear whether these diseases should be considered parallel ongoing independent nosologies or parts of a continuous pathological process.

AIH that developed de novo after liver transplantation performed for liver failure associated with other diseases is considered as a separate nosology [1, 5].

Autoimmune hepatitis is found everywhere. The prevalence of AIH in European countries is about 170 cases per 1 million population. Moreover, up to 80% of all cases are type 1 AIH. Type 2 AIH is unevenly distributed - up to 4% in the USA and up to 20% in Europe.

Mostly women are affected (the sex ratio among patients in European countries is 3–4:1). The age of the patients ranges from 1 year to 80 years, the average age is about 40 years [6].

Causes

The cause of autoimmune hepatitis (in other words, the reason why the immune system attacks and destroys healthy liver cells) is still not clear. There is an assumption that inflammatory-necrotic liver damage may be associated with an imbalance of effector and regulatory T cells (cells of the immune system), and may arise as a result of adverse environmental influences or due to genetic predisposition.

Without appropriate treatment, the disease progresses and the following complications may develop: ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity), gastrointestinal bleeding due to impaired blood flow in the esophagus and stomach, cirrhosis of the liver (and liver cancer due to the increased risk associated with cirrhosis) , kidney failure.

Etiopathogenesis

The etiology of AIH is unknown, but the development of the disease is thought to be influenced by both genetic and environmental factors.

An important link in the pathogenesis may be certain alleles of the HLA II genes (human leukocyte antigen type II, Human leucocyte antigen II) and genes associated with the regulation of the immune system [7, 8].

It is worth mentioning separately about AIH, which is part of the clinical picture of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome (autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome, autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy, APECED). This is a monogenic disease with autosomal recessive inheritance associated with a mutation in the AIRE1 gene. Thus, in this case, genetic determination is a proven fact [4, 9].

The autoimmune process in AIH is a T-cell immune response, accompanied by the formation of antibodies to autoantigens and inflammatory tissue damage.

Pathogenesis factors of AIH:

- pro-inflammatory factors (cytokines) produced by cells during the immune response. Indirect confirmation may be that autoimmune diseases are often associated with bacterial or viral infections;

- inhibition of the activity of regulatory T cells, which play a critical role in maintaining tolerance to autoantigens;

- dysregulation of apoptosis, normally a mechanism that controls the immune response and its “correctness”;

- molecular mimicry is a phenomenon where the immune response against external pathogens can also affect its own components that are structurally similar to them. Viral agents may play an important role in this. Thus, several studies have shown the presence of a pool of circulating autoantibodies (ANA, SMA, anti-LKM-1) in patients suffering from viral hepatitis B and C [2,4];

- factor of toxic drug effects on the liver. Some researchers associate the manifestation of AIH with the use of antifungal drugs and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Clinic

In approximately a quarter of patients, AIH begins acutely, and even rare cases of acute liver failure have been described. Acute hepatitis with jaundice is more common in children and young people; in this same group, a fulminant course of the disease is more often observed [6].

It should be noted that some patients with symptoms of acute AIH in the absence of treatment may experience spontaneous improvement and normalization of laboratory parameters. However, a repeat episode of AIH usually occurs within a few months. Histologically, a persistent inflammatory process in the liver is also determined [6].

More often, the clinical picture of AIH corresponds to the clinical picture of chronic hepatitis and includes symptoms such as asthenia, nausea, vomiting, pain or discomfort in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, jaundice, sometimes accompanied by skin itching, arthralgia, and less commonly, palmar erythema, telangiectasia, hepatomegaly [2, 6]. With developed liver cirrhosis, symptoms of portal hypertension and encephalopathy may prevail.

AIH can be associated with autoimmune diseases of various profiles:

- hematological (thrombocytopenic purpura, autoimmune hemolytic anemia);

- gastroenterological (inflammatory bowel diseases);

- rheumatological (rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren's syndrome, systemic scleroderma);

- endocrine (autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus);

and other profiles (erythema nodosum, proliferative glomerulonephritis) [1, 2].

Diagnosis of AIH

Diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis is based on:

- research results: clinical, serological and immunological;

- excluding other liver diseases that occur with or without an autoimmune component (chronic viral hepatitis, toxic hepatitis, non-alcoholic steatosis, Wilson's disease, hemochromatosis, and cryptogenic hepatitis).

AIH types 1 and 3 are similar in terms of patient demographics, HLA profile, inflammatory activity, and response to therapy. AIH type 2 has significant differences, affecting more often children and adolescents and usually having an acute onset and a more severe course.

It is important to be aware of the possibility of AIH in patients with elevated liver enzyme levels, as well as in patients with liver cirrhosis. If there are signs of cholestasis, primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis should be included in the range of pathologies for differential diagnosis.

The clinical search includes the determination of such laboratory parameters as the activity of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase (ALT and AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), level of albumin, gamma globulin, IgG, bilirubin (bound and unbound). It is also necessary to determine the level of autoantibodies in the blood serum and obtain histological examination data [9].

For patients who failed to achieve remission and stop the development of cirrhosis within 4 years, the method of choice is liver transplantation. The 10-year survival rate in patients who have undergone this operation is quite high (75–85%), however, the rate of relapses reaches 11–41%. The persistence of autoantibodies in the blood is not a sign of relapse of AIH and does not predict its development.

Visual diagnostic methods (ultrasound, CT, MRI) do not make a decisive contribution to the diagnosis of AIH, however, they make it possible to establish the fact of progression of AIH and the outcome in cirrhosis of the liver, as well as exclude the presence of focal pathology. In general, diagnosis is based on 4 points [10]:

- Hypergammaglobulinemia is one of the most accessible tests. An increase in the level of IgG with normal levels of IgA and IgM is indicative. However, there are difficulties when working with patients with initially low IgG levels, as well as with patients (5–10%) with normal IgG levels in AIH. In general, this test is considered useful in monitoring disease activity during treatment [6].

- Presence of autoantibodies. At the same time, antibodies of the ANA and SMA types are not a specific sign of autoimmune hepatitis, nor are anti-LKM-1 antibodies, which are found in 1/3 of children and a small proportion of adults suffering from AIH. Only anti-SLA/LP antibodies are specific for AIH. Antibodies to double-stranded DNA can also be detected in patients.

- Histological changes are assessed in conjunction with previous indicators. There are no strictly pathognomonic signs of AIH, but many changes are quite typical. The portal fields are infiltrated to varying degrees by T lymphocytes and plasma cells. Inflammatory infiltrates are capable of “cutting off” and destroying individual hepatocytes, penetrating into the liver parenchyma - this phenomenon is described as stepwise (fine-focal necrosis), borderline hepatitis. Balloon degeneration of hepatocytes occurs inside the lobules with their swelling, formation of rosettes and necrosis of individual hepatocytes - Fig. 2. The fulminant course is often characterized by centrilobular necrosis. Bridge-like necrosis connecting adjacent periportal fields may also be observed [2, 6].

- Absence of markers of viral hepatitis.

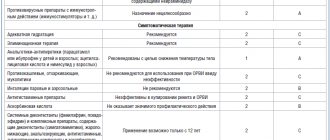

- The International AIH Research Group has developed a scoring system to assess the reliability of the diagnosis - Table. 1.

The hepatitis B virus is 100 times more contagious than HIV (human immunodeficiency virus).

Despite the widespread introduction of vaccination against hepatitis B, the prevalence of the disease remains high. In different regions of Russia, the prevalence of carriage of the virus ranges from 1.5% to 11.5%. As with hepatitis C, the source of infection is the blood of an infected person. The routes of infection are similar: the use of non-sterile needles, instruments for various medical and non-medical (piercing, tattoos, manicure/pedicure) manipulations, the use of personal hygiene items of an infected person in everyday life (razor, scissors, toothbrush, etc.), unprotected sexual contact, transmission of the virus from an infected mother to her child. The hepatitis B virus is more stable in the external environment and more contagious than the hepatitis C viruses and human immunodeficiency viruses. Therefore, the natural routes of transmission of the B virus (sexual transmission and mother-to-child transmission) are more significant for this virus.

Treatment of autoimmune hepatitis

AIH refers to diseases for which treatment can significantly increase patient survival.

Indications for starting treatment are:

- an increase in AST activity in the blood serum by 10 times compared to the norm or 5 times, but in combination with a twofold increase in the level of gamma globulin;

- the presence of bridge-like or multilobular necrosis during histological examination;

- pronounced clinic - general symptoms and symptoms of liver damage.

Less pronounced deviations in laboratory parameters in combination with a less pronounced clinical picture are a relative indication for treatment.

In case of inactive cirrhosis of the liver, the presence of signs of portal hypertension in the absence of signs of active hepatitis, and “mild” hepatitis with stepwise necrosis and without clinical manifestations, treatment is not indicated [1, 9]. The general concept of therapy for AIH involves achieving and maintaining remission. The basic immunosuppressive therapy is glucocorticosteroids (prednisolone) as monotherapy or in combination with azathioprine [2, 6, 9, 11]. Therapy continues until remission is achieved, and it is important to achieve histologically confirmed remission, which may lag behind the normalization of laboratory parameters by 6–12 months. Laboratory remission is described as normalization of the levels of AST, ALT, gamma globulin, IgG [2].

Maintenance therapy with lower doses of immunosuppressive drugs to reduce the likelihood of relapse after achieving remission is carried out for at least 2 years.

In addition, the possibility of using ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) drugs for autoimmune hepatitis as concomitant therapy or even monotherapy is being discussed [11]. AIH in patients receiving UDCA drugs in mono- and combination therapy was characterized by a milder course and accelerated normalization of laboratory parameters.

Symptoms

Symptoms of autoimmune hepatitis vary from person to person and may be mild or sudden in the early stages.

Symptoms of AIH include:

- increased fatigue, tiredness;

- discomfort and pain in the abdomen;

- skin rash, itching, formation of arachnoid angiomas;

- yellowness of the skin and visible mucous membranes (jaundice);

- joint pain;

- dark colored urine;

- amenorrhea (cessation of menstruation);

- hepatomegaly;

- splenomegaly.

Response to treatment

The results of treatment with prednisone and azathioprine for AIH may be as follows:

- A complete response is normalization of laboratory parameters, which persists for a year during maintenance therapy. At the same time, the histological picture is normalized (with the exception of small residual changes). The full effectiveness of treatment is also indicated in cases where the severity of clinical markers of autoimmune hepatitis significantly decreases, and during the first months of therapy laboratory parameters improve by at least 50% (and in the next 6 months they do not exceed the normal level by more than 2 times) .

- Partial response—there is an improvement in clinical symptoms and a 50% improvement in laboratory values within the first 2 months. Subsequently, the positive dynamics are maintained, but complete or almost complete normalization of laboratory parameters does not occur during the year.

- Lack of therapeutic effect (ineffectiveness of treatment) - an improvement in laboratory parameters by less than 50% in the first 4 weeks of treatment, and no further decrease (regardless of clinical or histological improvement) occurs.

- An unfavorable outcome of therapy is characterized by a further deterioration in the course of the disease (although in some cases there is an improvement in laboratory parameters).

Disease relapse is said to occur when, after achieving a complete response, clinical symptoms reappear and laboratory parameters deteriorate.

Typically, therapy has a good effect, but in 10–15% of patients it does not lead to improvement, although it is well tolerated. The reasons for the ineffectiveness of therapy can be [6]:

- lack of response to the drug;

- lack of compliance and adherence to therapy;

- drug intolerance;

- presence of cross syndromes;

- hepatocellular carcinoma.

Other immunosuppressants are also used as alternative drugs for the treatment of autoimmune hepatitis: budesonide, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, methotrexate [1, 2, 6, 11].

Clinical case

An eight-year-old girl was observed for skin rashes (erythematous and nodular elements without any discharge on the lower extremities) that had been bothering her for 5–6 months.

I used topical remedies for eczema for two months, there was no improvement. Later, discomfort in the epigastric region, weakness, and occasional nausea and vomiting arose. The rashes were localized on the legs. Histological examination of a skin biopsy revealed infiltration of subcutaneous fatty tissue with lymphocytes without signs of vasculitis. These phenomena were regarded as erythema nodosum. Upon examination, mild hepatosplenomegaly was revealed, otherwise the somatic status was without pronounced features, the condition was stable.

According to the results of laboratory tests:

- CBC: leukocytes - 4.5×109/l; neutrophils 39%, lymphocytes 55%; signs of hypochromic microcytic anemia (hemoglobin 103 g/l); platelets - 174,000/μl, ESR - 24 mm/h;

- biochemical blood test: creatinine - 0.9 mg/dl (normal 0.3–0.7 mg/dl); total bilirubin - 1.6 mg/dl (normal 0.2-1.2 mg/dl), direct bilirubin - 0.4 mg/dl (normal 0.05-0.2 mg/dl); AST - 348 U/l (normal - up to 40 U/l), ALT - 555 U/l (normal - up to 40 U/l); alkaline phosphatase - 395 U/l (normal - up to 664 U/l), lactate dehydrogenase - 612 U/l (normal - up to 576 U/l).

Indicators of the hemostasis system (prothrombin time, international normalized ratio), the level of total protein, serum albumin, gamma globulin, the level of ferritin, ceruloplasmin, alpha-antitrypsin, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase are within the reference values.

No HBs antigen, antibodies to HBs, HBc, or antibodies to hepatitis A and C virus were detected in the blood serum. Tests for cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, toxoplasma, and brucella were also negative. The ASL-O titer is within the normal range. There is no evidence for diabetes mellitus, thyroiditis, Graves' disease, proliferative glomerulonephritis.

Ultrasound of the abdominal organs visualized an enlarged liver with an altered echostructure, without signs of portal hypertension and ascites. Ophthalmological examination did not reveal the presence of a Kayser-Fleischer ring.

Anti-SMA antibody titer - 1:160, ANA, AMA, anti-LKM-1 antibodies were not detected. The patient is positive for haplotypes HLA DR3, HLA DR4.

Histological examination of the liver biopsy revealed fibrosis, lymphocytic infiltration, formation of hepatocyte rosettes and other signs of chronic autoimmune hepatitis.

The patient was diagnosed with autoimmune hepatitis type 1 associated with erythema nodosum, and therapy with prednisolone and azathioprine was started. The IAIHG score was 19 points before treatment, which is characterized as “definite AIH.”

After 4 weeks of therapy, relief of general clinical symptoms and normalization of laboratory parameters were noted. After 3 months of therapy, the skin rashes completely regressed. 6 months after the end of therapy, the patient’s condition was satisfactory, laboratory parameters were within the reference values.

Adapted from Kavehmanesh Z. et al. Pediatric Autoimmune Hepatitis in a Patient Who Presented With Erythema Nodosum: A Case Report. Hepatitis monthly, 2012. V. 12. - N. 1. - P. 42–45.

Thus, AIH is a fairly rare and relatively treatable disease. With the introduction of modern immunosuppressive therapy protocols, the 10-year survival rate of patients reaches 90%. The prognosis is less favorable in patients with autoimmune hepatitis type 2, especially in children and adolescents, in whom AIH progresses much faster, and the effectiveness of therapy is generally lower. You should also be aware of the risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (4–7% within 5 years after diagnosis of liver cirrhosis).

List of sources

- Viral hepatitis and cholestatic diseases / Eugene R. Schiff, Michael F. Sorrell, Willis S. Maddray; lane from English V. Yu. Khalatova; edited by V. T. Ivashkina, E. A. Klimova, I. G. Nikitina, E. N. Shirokova. - M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2010.

- Kriese S., Heneghan MA Autoimmune hepatitis. Medicine, 2011. V. 39. - N. 10. - P. 580–584.

- Autoimmune hepatitis and its variant forms: classification, diagnosis, clinical manifestations and new treatment options: a manual for doctors. T. N. Lopatkina. - M. 4TE Art, 2011.

- Longhia MS et al. Aethiopathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis. Journal of Autoimmunity, 2010. N. 34. - P. 7–14.

- Muratori L. et al. Current topics in autoimmune hepatitis. Digestive and Liver Disease, 2010. N. 42. - P. 757–764.

- Lohse AW, Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune hepatitis. Journal of Hepatology, 2011. V. 55. - N. 1. - P. 171–182.

- Oliveira LC et al. Autoimmune hepatitis, HLA and extended haplotypes. Autoimmunity Reviews, 2011. V. 10. - N. 4. - P. 189–193.

- Agarwal, K. et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to type 1 autoimmunehepatitis. Hepatology, 2000. V. 31. - N. 1. - P. 49–53.

- Manns MP et al. Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis. Hepatology, 2010. V. 51. - N. 6. - P. 2193–2213.

- Lohse AW, Wiegard C. Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune hepatitis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology, 2011. V. 25. - N. 6. - P. 665–671.

- Strassburg CP, Manns MP Therapy of autoimmune hepatitis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology, 2011. V. 25. - N. 6. - P. 673–687.

- Ohira H., Takahashi A. Current trends in the diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis in Japan. Hepatology Research, 2012. V. 42. - N. 2. - P. 131–138.