How common is non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? Forms of the disease

The content of the article

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, known as NAFLD, is the most common disease of this organ. However, knowledge about it, even among doctors, is still insufficient.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

NAFLD is estimated to be very common. For example, among overweight and obese people, the percentage of patients with such pathology reaches 50%. These values are similar to or higher than the number of people with hypertension or type 2 diabetes.

Meanwhile, in 5% of patients the disease takes an advanced form called NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and in 0.5% it progresses to fatal cirrhosis of the liver. The latter percentages seem small, but in terms of the total number of cases they are huge.

Therefore, NAFLD includes: “simple” steatosis and the more dangerous non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. When the latter form appears, a very serious complication may occur—liver cirrhosis.

1.General information

Steatosis, or fatty infiltration, is an accumulation of lipid compounds in hepatocytes (parenchymal, functionally specialized liver cells). Hepatitis is an inflammatory process in the liver. Accordingly, steatohepatitis is a disease that combines the signs and patterns of both pathological processes. The clarification “non-alcoholic” (syn. “pseudo-alcoholic”, “diabetic”, etc.) is necessary because the histological picture of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is identical to fatty degeneration of liver cells in alcoholics, however, it develops in individuals for whom it is reliably known that there is no abuse of such kind.

This nosological unit was identified relatively recently (1980) and is actively being studied by hepatologists around the world, since many issues have not been clarified to this day. However, quite extensive statistical material has been accumulated. In particular, the pronounced endemicity (regional dependence) of the incidence of NASH is known: if in Japan its prevalence in the general population is slightly more than 1%, then in Western countries, according to various estimates, the incidence ranges from 7% to 11%. It has also been reliably established that the probability of “starting” the steatohepatitis process depends on age (persons aged 45-55 years old fall into the risk category) and gender (women get sick three times more often).

It should be understood that the data presented are purely statistical trends, although quite strong; in real clinical practice, NASH is found in patients of any gender and age.

A must read! Help with treatment and hospitalization!

Why is the disease called insidious? No signs or symptoms

The disease does not show any symptoms for a very long time (and sometimes not at all). And those that the patient himself experiences, and that the doctor could detect during the examination of the patient (signs).

In simple steatosis, if symptoms occur, they are very nonspecific, meaning they can also occur in a number of other diseases besides NAFLD. Experts typically report two of these symptoms:

- fatigue;

- weak, usually dull pain in the upper right corner of the abdomen.

The condition is similar to other "progressive" diseases: hypertension and type 2 diabetes. But unlike non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, these diseases usually do not develop complications before they can be diagnosed.

In the case of NASH, i.e. a more dangerous form of NAFLD that causes liver degeneration and fibrosis), symptoms may be more typical. More often than with simple steatosis, the following appear:

- dull or aching pain in the right upper abdomen;

- a more intense feeling of tiredness, sometimes it can be severe fatigue;

- unexplained weight loss;

- weakness.

A complication of NASH, liver cirrhosis, is also accompanied by a number of symptoms:

- jaundice, i.e. yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes;

- skin itching;

- swelling of the entire leg or limited swelling around the ankles or feet;

- nausea, loss of appetite and/or weight loss;

- enlarged abdomen due to fluid accumulation (ascites);

- confusion.

Ascites

But let us repeat once again - these symptoms appear late and relate not to the most common “simple” fatty steatosis, but to a more dangerous form - NASH and cirrhosis of the liver.

Stages of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

There are several stages of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis:

- steatosis, which is the accumulation of fat in liver cells (hepatocytes);

- non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, when inflammation develops in the parenchyma of the organ;

- fibrosis – excessive growth of connective tissue against the background of inflammation and death of liver cells;

- Cirrhosis is an irreversible disorder of the liver structure due to progressive fibrosis.

Thus, it is the development of the inflammatory process or the transformation of steatosis into non-alcoholic steatohepatitis that is crucial for the course and prognosis of the disease. If steatosis can exist for a long time without posing a serious threat to the liver, then steatohepatitis is actually a trigger for the progression of the disease, which can result in cirrhosis.

Despite the relatively favorable course, steatosis can transform into non-alcoholic steatohepatitis at any time, especially with continued exposure to risk factors and the absence of adequate treatment. This is facilitated by the high biological activity of adipose tissue, leading to excess production of free oxygen radicals and special molecules - cytokines. Free oxygen radicals cause oxidative stress, and cytokines cause inflammation. Both of these processes are critical for hepatocyte damage.

How is NAFLD diagnosed?

The question arises of how to detect this disease in general, since in most cases it is asymptomatic.

NAFLD is diagnosed mainly based on ultrasound of the abdominal cavity, including the liver. Interestingly, fatty liver disease in most cases is discovered by chance when an ultrasound is performed for other reasons, for example, to detect gallstones or to diagnose abdominal pain.

Fatty liver is very characteristic on ultrasound images. Radiologists say that the liver “glows” on the screen and is hyperechoic (its echo is greater than that of the surrounding tissue).

It is important to understand that fatty liver disease can also occur with other conditions or diseases, such as alcohol abuse, certain medications, or hepatitis C.

Early detection of fatty tissue using ultrasound is very important. Early diagnosis of NAFLD helps prevent exacerbation of the disease - NASH, as well as prevent the development of complications, the most important of which is cirrhosis of the liver. Therefore, gastroenterologists recommend regular ultrasound examinations of the liver (abdominal cavity), even if there are no symptoms. This is especially true for patients from risk groups.

Ultrasound of the liver (abdominal cavity)

A group or risk factor is a statistical concept that limits a group of people with a particular condition or disease where the likelihood of developing a particular disease (in our case NAFLD) is higher than in the general population. Therefore, if the risk of developing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the entire population is 20-25%, then in type 2 diabetes mellitus this figure reaches 75%. Therefore, type 2 diabetes is a risk factor for the development of NAFLD.

According to European recommendations, ultrasound examination of the abdominal cavity should be carried out for people with:

- obesity;

- risk factors for metabolic disorders - increased waist circumference, hyperglycemia [increased blood sugar levels], hypertriglyceridemia [increased triglyceride levels in the blood], decreased HDL cholesterol, hypertension;

- persistent increase in alanine aminotransferase (ALT).

Non-alcoholic liver steatosis, diagnosis, treatment approaches

Non-alcoholic liver steatosis (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), fatty liver, fatty liver, fatty infiltration) is a primary liver disease or syndrome formed by excessive accumulation of fats (mainly triglycerides) in the liver. If we consider this nosology from a quantitative point of view, then “fat” should be at least 5–10% of the liver weight, or more than 5% of hepatocytes should contain lipids (histologically) [1].

If you do not intervene during the course of the disease, then in 12–14% NAFLD transforms into steatohepatitis, in 5–10% of cases into fibrosis, in 0–5% fibrosis transforms into cirrhosis of the liver; in 13% of cases, steatohepatitis immediately transforms into liver cirrhosis [2].

These data make it possible to understand why this problem is of general interest today; if the etiology and pathogenesis are clear, then it will be clear how to most effectively treat this common pathology. It is already clear that in some patients this may be a disease, and in others it may be a symptom or syndrome.

Recognized risk factors for developing NAFLD are:

- obesity;

- diabetes mellitus type 2;

- fasting (sharp weight loss > 1.5 kg/week);

- parenteral nutrition;

- presence of ileocecal anastomosis;

- bacterial overgrowth in the intestines;

- many drugs (corticosteroids, antiarrhythmic drugs, antitumor drugs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, synthetic estrogens, some antibiotics and many others) [3–5].

The listed risk factors for NAFLD show that a significant part of them are components of metabolic syndrome (MS), which is a complex of interrelated factors (hyperinsulinemia with insulin resistance - type 2 diabetes mellitus (type 2 diabetes), visceral obesity, atherogenic dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, microalbuminuria, hypercoagulability, hyperuricemia, gout, NAFLD). MetS forms the basis of the pathogenesis of many cardiovascular diseases and indicates their close connection with NAFLD. Thus, the range of diseases that form NAFLD is significantly expanding and includes not only steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis of the liver, but also arterial hypertension, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction and heart failure. At least, if the direct connections of these conditions require further study of the evidence base, their mutual influence is undoubtedly [6].

Epidemiologically, there are primary (metabolic) and secondary NAFLD. The primary form includes most conditions that develop with various metabolic disorders (they are listed above). The secondary form of NAFLD includes conditions that are formed by: nutritional disorders (overeating, starvation, parenteral nutrition, trophological deficiency - kwashiorkor); medicinal effects and relationships that are realized at the level of hepatic metabolism; hepatotropic poisons; intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome; diseases of the small intestine accompanied by indigestion syndrome; resection of the small intestine, small bowel fistula, functional pancreatic insufficiency; liver diseases, including genetically determined ones, acute fatty disease of pregnant women, etc. [7–9].

If the doctor (researcher) has morphological material (liver biopsy), then three degrees of steatosis are morphologically distinguished:

- 1st degree - fatty infiltration <33% of hepatocytes in the field of view;

- 2nd degree - fatty infiltration of 33–66% of hepatocytes in the field of view;

- Grade 3—fatty infiltration of >66% of hepatocytes in the field of view.

Having given the morphological classification, we must state that these data are conditional, since the process is never uniformly diffuse, and at each specific moment we are considering a limited fragment of tissue, and we are confident that in another biopsy we will get the same Most likely, no, and, finally, the 3rd degree of fatty liver infiltration should be accompanied by functional liver failure (at least in some components: synthetic function, detoxification function, biliary capacity, etc.), which is practically not characteristic of NAFLD.

The above material highlights factors and metabolic states that may be involved in the development of NAFLD, and proposes the “two-hit” theory as a modern model of pathogenesis:

the first is the development of fatty degeneration; the second is steatohepatitis.

With obesity, especially visceral obesity, the supply of free fatty acids (FFA) to the liver increases, and liver steatosis develops (the first blow). Under conditions of insulin resistance, lipolysis in adipose tissue increases, and excess FFA enters the liver. As a result, the amount of fatty acids in the hepatocyte increases sharply, and fatty degeneration of hepatocytes is formed. Oxidative stress develops simultaneously or sequentially—a “second blow” with the formation of an inflammatory response and the development of steatohepatitis. This is largely due to the fact that the functional capacity of mitochondria is depleted, microsomal lipid oxidation in the cytochrome system is turned on, which leads to the formation of reactive oxygen species and an increase in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokinins with the formation of inflammation in the liver, death of hepatocytes caused by the cytotoxic effects of TNF-alpha1 - one of the main inducers of apoptosis [10, 11]. Subsequent stages of the development of liver pathology and their intensity (fibrosis, cirrhosis) depend on the remaining factors in the formation of steatosis and the lack of effective pharmacotherapy.

Diagnosis of NAFLD and its progression conditions (liver steatosis, steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis)

Fatty liver degeneration is a formally morphological concept, and it would seem that diagnosis should be reduced to a liver biopsy. However, such a decision has not been made by international gastroenterological associations and the issue is being discussed. This is due to the fact that fatty degeneration is a dynamic concept (it can be activated or undergo reverse development, and can be both relatively diffuse and focal in nature). The biopsy is always represented by a limited area, and the interpretation of the data is always quite conditional. If we recognize biopsy as a mandatory diagnostic criterion, then it should be performed quite often; the biopsy itself is fraught with complications, and the research method should not be more dangerous than the disease itself. The absence of a decision on a biopsy is not a negative factor, especially since today liver steatosis is a clinical and morphological concept with the presence of many factors involved in pathogenesis.

From the data presented above, it is clear that diagnosis can begin at different stages of the disease: steatosis → steatohepatitis → fibrosis → cirrhosis, and the diagnostic algorithm should include methods that determine not only fatty degeneration, but also its stage.

Thus, at the stage of liver steatosis, the main symptom is hepatomegaly (discovered by chance or during a clinical examination). The biochemical profile (aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gammaglutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), cholesterol, bilirubin) determines the presence or absence of steatohepatitis. If the level of transaminases increases, it is necessary to conduct virological studies (which will either confirm or reject viral forms of hepatitis), as well as diagnosis of other forms of hepatitis: autoimmune, biliary, primary sclerosing cholangitis. Ultrasound examination not only reveals an increase in the size of the liver and spleen, but also signs of portal hypertension (by the diameter of the splenic vein and the size of the spleen). Less commonly used (and perhaps even known) is the assessment of fatty infiltration of the liver, which consists of measuring the “attenuation column”, the dynamics of which at different periods of time can be used to judge the degree of fatty degeneration (Fig.) (ultrasound technique is described) [12].

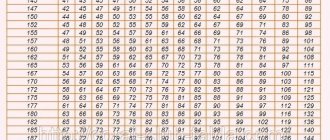

Earlier models of ultrasound devices assessed densitometric indicators (the dynamics of which could be used to judge the dynamics and degree of steatosis). Currently, densitometric indicators are obtained using computed tomography of the liver. When considering the pathogenesis of NAFLD, a general examination and anthropometric indicators are assessed (determining body weight and waist circumference - WC). Since MS occupies a significant place in the formation of steatosis, in diagnosis it is necessary to evaluate: abdominal obesity - WC > 102 cm in men, > 88 cm in women; triglycerides > 150 mg/dl; high-density lipoprotein (HDL): <40 mg/dL in men and <50 ml/dL in women; blood pressure (BP) > 130/85 mm Hg. st; body mass index (BMI) > 25 kg/m2; fasting blood glucose > 110 mg/dL; glycemia 2 hours after a glucose load 110–126 mg/dL; Type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance.

The data presented above is recommended by WHO and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. An important diagnostic aspect is also the establishment of fibrosis and its degree. Despite the fact that fibrosis is also a morphological concept, it is determined by various calculated indicators. From our point of view, the Bonacini discriminant scoring scale, which determines the fibrosis index (IF), is a convenient method corresponding to the stages of fibrosis. We conducted a comparative study of the calculated IF index with the results of biopsies. These indicators are presented in table. 1 and 2.

Practical meaning of IF:

1) IF, assessed using a discriminant scoring scale, significantly correlates with the stage of liver fibrosis according to puncture biopsy; 2) studying IF makes it possible to assess the stage of fibrosis with a high degree of probability and use it for dynamic monitoring of the intensity of fibrosis formation in patients with chronic hepatitis, NAFLD and other diffuse hepatic diseases, including for assessing the effectiveness of therapy [13].

And finally, if a puncture biopsy of the liver is performed, it is prescribed, as a rule, in the case of differential diagnosis of tumor formations, including the focal form of steatosis. At the same time, in the liver tissue of these patients the following is detected:

- fatty liver degeneration (large-droplet, small-droplet, mixed);

- centrilobular (less often portal and periportal) inflammatory infiltration with neutrophils, lymphocytes, histiocytes;

- fibrosis (perihepatocellular, perisinusoidal and perivenular) of varying severity.

The diagnosis of NAFLD (liver steatosis) is formulated based on the combination of the following symptoms and conditions:

- obesity;

- MS;

- malabsorption syndrome (as a consequence of ileojejunal anastomosis, biliary-pancreatic stoma, extended resection of the small intestine);

- long-term (more than two weeks parenteral nutrition).

Diagnosis also involves excluding the main hepatic nosological forms:

- alcoholic liver damage;

- viral infection (B, C, D, TTV);

- Wilson–Konovalov disease (blood ciruloplasmin levels are examined);

- congenital alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency disease);

- hemachromatosis;

- autoimmune hepatitis;

- drug-induced hepatitis (drug history and withdrawal of a possible drug that forms intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL)).

Thus, the diagnosis is formed from the definition of hepatomegaly, the identification of pathogenetic factors contributing to steatosis, and the exclusion of other diffuse forms of liver damage.

Treatment principles

Since the main factor in the development of non-alcoholic liver steatosis is excess body weight (BW), reducing BW is a fundamental condition for the treatment of patients with NAFLD, which is achieved by lifestyle changes, including dietary measures and physical activity, including in cases where the need is absent in reducing BM [14]. The diet should be hypocaloric - 25 mg/kg per day with a limitation of animal fats (30-90 g/day) and a reduction in carbohydrates (especially those that are quickly digestible) - 150 mg/day. Fats should be predominantly polyunsaturated, which are found in fish and nuts; It is important to consume at least 15 grams of fiber from fruits and vegetables, as well as foods rich in vitamin A.

In addition to the diet, you need at least 30 minutes of daily aerobic physical activity (swimming, walking, gym). Physical activity itself reduces insulin resistance and improves quality of life [15].

The second important component of therapy is the impact on metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in particular. Of the drugs aimed at its correction, metformin has been the most studied [16, 17]. It has been shown that treatment with metformin leads to an improvement in laboratory and morphological indicators of inflammatory activity in the liver. Insulin sensitizers are used in type 2 diabetes, but a meta-analysis did not show any benefit from their effect on insulin resistance [18].

The third component of therapy is to avoid the use of hepatotoxic drugs and drugs that cause liver damage (the main morphological substrate of this damage is liver steatosis and steatohepatitis). In this regard, it is important to take a drug history and avoid drug(s) that damage the liver.

Since bacterial overgrowth syndrome (SIBO) plays an important role in the formation of liver steatosis, it must be diagnosed and corrected (drugs with antibacterial action - preferably non-absorbable; probiotics; motility regulators, liver protectors), and the choice of therapy depends on the initial pathology , which forms SIBO.

Today, the issue of using liver protectors is not resolved entirely correctly. There are works that show their low efficiency, there are works that show their high efficiency. It appears that their use does not take into account the stage of NAFLD. If there are signs of steatohepatitis, fibrosis, or cirrhosis of the liver, then their use seems justified. I would like to present analytical data on the basis of which and depending on the number of factors involved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD, a hepatoprotector can be selected (Table 3).

From the presented table it is clear (the most commonly used protectors are introduced, if desired, it can be expanded by introducing other protectors) that ursodeoxycholic acid preparations (Ursosan) act on the maximum number of pathogenetic links of liver damage.

We would like to present the results of Ursosan treatment of patients with NAFLD. 30 patients were studied (15 of them had obesity as the basis, 15 had MS; there were 20 women, 10 men; age from 30 to 65 years (average age 45 ± 6.0 years).

The selection criteria were: increase in AST level - 2–4 times; ALT - 2–3 times; BMI > 31.1 kg/m2 in men and BMI > 32.3 kg/m2 in women. Patients received Ursosan at a dose of 13–15 mg/kg body weight per day; 15 patients for 2 months, 15 patients continued taking the drug for up to 6 months. The results of treatment are presented in table. 4–6.

The exclusion criteria were: viral nature of the disease; concomitant pathology in the stage of decompensation; taking drugs that can potentially form (maintain) fatty liver degeneration.

Group 2 continued to receive Ursosan at the same dose for 6 months (with normal biochemical parameters). At the same time, appetite stabilized, and body weight gradually (1 kg/month) decreased. According to ultrasound data, the structure and size of the liver did not change significantly, the dynamics along the “attenuation column” continued (Table 6).

Thus, according to our data, the use of liver protectors in patients with NAFLD in the stage of steatohepatitis is effective, which is reflected in the normalization of biochemical parameters and a decrease in fatty infiltration of the liver (according to ultrasound, a decrease in the “attenuation column” of the signal), which in general is an important justification for their use.

Literature

- Morrison YA et al. Metformin for weight loss in pediatric patients taking psychotropic drugs // Am. Y Psychiatry. 2002. vol. 159, p. 655–657.

- Quote by: Shchekina M.I. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease // Cous. Med. T. 11, No. 8, p. 37–39.

- Isakov V. A. Statins and the liver: friends or enemies // Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology. Russian edition. T. 1, No. 5, 372–374.

- Diche AM NaSH: bench to bedside — lesons from aminal models. Presentation at the Session Falk Symposium 157, 2006.

- Lindor KD Jn on behalf of the UDCA/NASH Study group. Ursodeoxycholic acid for treatment of nonalcocholic steatohepatitis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled // Trial gastroenterology. 2003, 124 (Suppl): A-708.

- Drapkina O. M., Korneeva O. N. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk: the influence of female gender // Pharmateka. 2010, no. 15, p. 28–33.

- Shchekina M.I. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease // Cons. Med. T. 11, No. 8, 37–39.

- Bueverov A. O., Bogomolov P. O. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: rationale for pathogenetic therapy // Clinical perspectives of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2000, no. 1, 3–8.

- Savelyev V.S. Lipid distress - a syndrome in surgery. Materials of the 8th open session of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences. M. S. 56–57.

- Carieiro de Mura M. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis // Clinical perspectives of gastroenterology, hepatology. 2001, No. 3, p. 12–15.

- Augulo P. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease // New Engl. Y Med. 2002, vol. 346, p. 1221–1231.

- Sokolov L.K., Minushkin O.N. et al. Clinical and instrumental diagnosis of diseases of the organs of the hepatopancreato-duodenal zone. M., 1987, p. 30–39.

- Minushkin O. N. et al. Possibilities of clinical and laboratory assessment of liver fibrosis. In the book: Selected issues of clinical medicine. T. III. M., 2005, p. 96–102.

- Berrram SR, Venter Y, Stewart RY Weight loss in olese women exercise v. dietary education // S. Afr. Med. Y. 1990, 78, 15–18.

- Hickman Yg et al. Modest weight loss and physical activity in overweight patient with chronic liver disease result in suctaned improvements in alanine aminotransferase, fasting insulin, and quality of life // Gut. 2004, 53, 413–419.

- Bugianesi E. et al. A randomized controlled trial of merformin versus vitamin E or prescriptive diet in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease // Am. G. gastroenterol. 2005, vol. 100, No. 5 b, t. 1082–1090.

- Uygun A. et al. Metformin in the treatment of patients with non-alcoholic steatogepatitis // Phormacol Ther. 2004, vol. 19, no. 5, p. 537–544.

- Augelico F. et al. Drugs improving insulin resistance for non-alcogolic fatty liver disease and/or non-alcogolic steatogepatitis // Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007. CD005166.

O. N. Minushkin, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

FSBI UMTS Administrative Department of the President of the Russian Federation, Moscow

Contact information about the author for correspondence

How to treat NAFLD?

There is no miracle cure for this disease. In order for adipose tissue to regress, it is necessary to follow an appropriate low-calorie diet and regularly engage in physical activity at least 5 days a week for 30 minutes a day.

Regular physical activity

It is very important to be constantly monitored by a gastroenterologist so as not to miss complications.

4.Treatment

A generally accepted and universally effective treatment protocol for NASH has not been developed to date. However, in this case, etiopathogenetic therapy (aimed at eliminating the root causes of the disease) most often involves eliminating the above risk factors.

Thus, an individually developed diet is prescribed and other measures are taken to gradually normalize body weight. The intake is canceled or, if necessary, an alternative to medications that are potentially harmful to the liver, which are objectively indicated for the patient, is selected. Hepatoprotectors are prescribed, and according to indications - antibiotics, statins and other drugs.

Important Diet Guidelines for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

What to avoid in your diet:

- Eliminate saturated fats and red meat, and full-fat dairy products.

- It is important to avoid trans- and hydrogenated (hardened) fats, sugar, and alcohol.

- Eliminate all processed grain products (that is, do not use white flour or white rice in your diet).

Control of sodium content in the diet is mandatory - do not exceed 1500 mg of table salt per day.

Controlling sodium in your diet

Be careful with supplements and medications, many have contraindications for liver disease. Before taking them, you should definitely consult a gastroenterologist.

Useful products for patients with non-alcoholic liver disease:

- Extra virgin olive oil - for frying and three tablespoons per day orally.

- Fruits and vegetables (but watch the salt content!).

- High fiber foods such as whole grain bread and brown rice.

- Oily fish several times a week.

- Skinless chicken and only lean pork.

- Vegetable protein (legumes) without restrictions.

- Coffee - no more than 3 cups of filtered coffee per day.

Diagnosis of the disease

Ultrasound

Steatosis can be suspected by changes in the ultrasound picture of the liver. An ultrasound will detect an increase in its size and a change in the echo signal, indicating tissue heterogeneity.

Laboratory research

The onset of the inflammatory process is usually indicated by an increase in the level of liver enzymes - transaminases - in the blood. These enzymes, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, are normally found inside hepatocytes. During inflammation, damage and disruption of the integrity of liver cells occurs - cytolysis. As a result, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase enter the blood, which is accompanied by an increase in their levels above normal values.

Biopsy

A more accurate diagnosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis is possible by performing a liver biopsy. A biopsy involves taking a small area of organ tissue using a special thin needle; this area is examined under a microscope. Due to the fact that this procedure is painful, its implementation is not always justified. A biopsy as a method to make an accurate diagnosis is necessary in case of suspected presence of severe fibrosis or cirrhosis. In turn, these conditions can be assumed or excluded using non-invasive tests, such as elastometry, fibrotest, NAFLD fibrosis score.

Elastometry

Elastometry involves assessing the elasticity of liver tissue using ultrasound. Fibrotest and NAFLD fibrosis score are calculated scales based on mathematical processing of the values of laboratory and anthropometric indicators.

Symptoms and stages

NAFLD is often asymptomatic at first. The main stages of the disease are listed below6,7.

- Steatosis. Symptoms are almost completely absent. Steatosis is often discovered by chance when the patient seeks help for other reasons. However, fatigue, changes in appetite, and heaviness or discomfort in the right hypochondrium may occur6,7.

- Steatohepatitis. It can also be almost asymptomatic or accompanied by fatigue, weakness and discomfort or pain in the right side of the abdomen, not associated with meals7.

- Fibrosis. This is a condition in which connective tissue takes the place of hepatocytes.

- Cirrhosis. Serious impairment of liver function, which may result in liver failure. Spider veins may appear, the skin and mucous membranes turn yellow, the skin becomes dry, and itching occurs. There may be other symptoms: ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity), varicose veins of the esophagus and stomach and, as a result, bleeding6,7.