Getting rid of cancer is the cherished dream of all cancer patients; most patients are willing to pay a high price for a long life after cancer. Few people assume that life after treatment will be different in terms of pathophysiological sensations.

After radical treatment of stomach cancer (successful, because surgery is not always possible), the patient is faced with a new problem in the first days. Before the operation, the doctor will tell you that most of the stomach with the tumor will be removed. Typically, three-quarters, or the entire stomach, is removed. With these quarters, the ability to eat three times a day as usual will go away, but the patient has not yet thought about this loss. After surgery, a condition may arise that makes it impossible not only to eat normally, but also to feel normal after eating. We are talking about post-resection syndrome, which appeared due to the removal of part of the stomach. The condition is also called dumping syndrome from the English “dumping” - reset.

What do surgeons do with the stomach?

Stomach surgery is a surgical technique that has been clearly tested on thousands of patients, allowing the removal of some part or the entire organ with minimal losses. The smallest losses when removing part of the stomach means maximum preservation of the anatomical and physiological path of movement and digestion of food masses. Depending on the location of the tumor in the stomach, subtotal distal and proximal resections are performed, and complete removal of the stomach - gastrectomy - is still often performed.

Treatment

If we talk about the mild stage, then a diet based on high-calorie foods and vitamins comes to the rescue. But fluid intake must be limited. The same prescription applies to carbon consumption.

If the syndrome manifests itself in a moderate form, it is recommended to take special medications that reduce intestinal dysfunction. General strengthening therapy plays a significant role.

The severe form of the syndrome with insufficient therapy requires surgical manipulation, the essence of which is the interposition of part of the intestine.

Billroth operations and gastrectomy

The first surgeon who not only removed a part of the stomach affected by cancer on January 29, 1881, but also came out of a patient after a serious operation, was the Austrian Christian Albert Theodor Billroth. Later he was invited to see the great surgeon Pirogov, who was dying of oral cancer, and he also operated on the poet Nekrasov. The most important gastric operations, used to this day, were developed by Billroth and bear his name.

Gastric resection according to Billroth I consists of connecting the remainder of the stomach with the duodenum “end-to-end”. This does not correspond to human nature, which has formed a tightly closed muscular junction between the stomach and intestines. Evacuation of food masses from the operated stomach occurs quickly, however, the stomach partially plays the role of a reservoir for food. The mucous membrane of the stomach does not come into contact with the mucous membrane of the small intestine, which protects the latter from chronic ulcerations.

During gastric resection according to Billroth II, the remaining part of the stomach is sutured side-to-side with the jejunum, and the duodenum is excluded from circulation, which is not at all physiological. Subtotal gastrectomy according to Billroth II is very common in oncology; surgical tactics are determined by the cancerous tumor. It is with this option that dumping syndrome often develops.

Gastrectomy - complete removal of the stomach - necessarily leads to dumping syndrome. The esophagus is connected to the intestine, there is no reservoir for temporary storage of food with simultaneous digestion, the role of which was regularly performed by the stomach, food immediately enters the intestine, which is not adapted to unprepared food masses.

Possible complications

If the clinical picture of the syndrome is ignored for a long time, additional symptoms appear:

- Diseases of the gastrointestinal tract: peptic ulcer, enteritis, colitis, pancreatitis.

- Hypoglycemic conditions that provoke hormonal imbalance and the development of diabetes.

- Cachexia. The patient loses weight, which ultimately leads to significant weight loss and general exhaustion. Advanced pathology can lead to death.

Treatment of dumping syndrome without re-operation is possible provided emergency medication prescriptions are followed by an experienced specialist.

Manifestations of dumping syndrome

With stomach cancer, such pronounced biochemical disturbances occur in the patient’s body that even at the end of the last century, a quarter of patients died after surgery for unknown reasons. Today, the modern science of caring for postoperative patients has made it possible to forget about this sad quarter, however, the biochemical processes in the body of a gastric patient have not become smaller.

Rapid evacuation of food into the intestine leads to serious disturbances in biochemical processes, which affect the patient’s condition. A few minutes after eating, the patient literally becomes weak. The intensity of weakness is very different, from short-term and fundamentally not interfering with life and work, to a state of complete powerlessness.

Weakness is accompanied by strong palpitations and even pain in the chest, but these are not anginal pains caused by impaired myocardial nutrition - ischemia, but cardialgia, that is, as if pain in the heart. But it's not the heart that really hurts. With true heart pain, it hurts behind the sternum, the pain radiates to the arm, shoulder, jaw. But in especially severe cases of dumping syndrome, transient changes such as myocardial ischemia are noted on the ECG.

There are surges in blood pressure. My hands are shaking, my head is spinning, my ears are ringing. The patient is pale or, on the contrary, his face turns red, and he almost always sweats profusely. There is often a urge to urinate. Worries include nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, loud rumbling, belching, the urge to defecate, even diarrhea. The clinical picture is very varied, it is clear that the person is very ill, some require bed rest for a couple of hours after each meal.

The patient experiences fear, the symptoms are so unpleasant and varied. He may lose consciousness, which he does not always remember afterwards. Oddly enough, memories during dumping syndrome also do not always correspond to reality; amnesia after an attack is also possible. In this regard, they even identified an episodic variant, when the syndrome develops immediately after eating, accompanied by fear, which the patient does not remember well. The paroxysmal variant occurs a couple of hours after eating and leads to loss of consciousness and amnesia. And there is an objective biochemical reason for all this.

Symptoms of operated stomach syndrome

Depending on the severity of the disease, dumping syndrome can be mild, moderate or severe.

Mild severity:

- Attacks occur 1-2 times a month due to errors in diet. They last for 15-30 minutes and go away on their own after giving up foods rich in carbohydrates and milk. Diarrhea is sometimes noted.

Moderate severity:

- Attacks 4-5 times a week lasting from 1 to 2 hours are accompanied by rapid heartbeat, increased blood pressure, diarrhea, decreased performance, and a decrease in body weight up to 10 kg.

Severe severity:

- Attacks lasting 3-4 hours after any meal, possibly with loss of consciousness, cachexia.

How often is dumping syndrome observed?

This picture can appear after each meal, but during breakfast it is more pronounced, at lunch it appears a little less, and at dinner even less. Symptoms may last a few minutes or may last up to three hours. This is not all, because the patient also experiences weakness the rest of the time, but not so intense, and over time, asthenia develops, including a decrease in potency.

The frequency of development of dumping syndrome is unknown, in the specialized literature different figures are indicated - from 10 to 80%, it all depends on how focused the team of authors who wrote the article is in treating it. If the authors of the article are involved in the treatment of post-resection complications, then the frequency is high - they specifically collect such patients. If the scientific material was prepared by surgeons, then a full statement of dumping syndrome in operated patients is far from ideal and real; as a rule, only a severe course is monitored.

In most cases, the syndrome is mild with partially blurred clinical signs; a severe course is typical for women who have undergone surgery. Again, it is not really known how many patients there are with a severe syndrome; options range from one to ten per hundred operated on. Some operated patients who experience weakness after eating do not even suspect the presence of mild dumping syndrome, which could be corrected if a diagnosis were made.

Diagnostic methods in Medscan

Dumping syndrome is a complication of surgical treatment of gastric cancer or gastric metastases in various oncopathologies. A preliminary diagnosis is made based on the clinical picture. Mandatory diagnosis of dumping syndrome for stomach cancer includes:

- Laboratory examination methods: blood and urine tests. The condition of the liver (liver tests, alkaline phosphatase level), blood vessels (cholesterol), and pancreas (amylase, glucose) is determined.

- Endoscopy and radiographic examination of the esophagus and stomach. The study helps to find out the nature of changes in organs after surgery.

- CT, MRI of adjacent tissues.

- Test with sugar. The patient's pulse rate and blood pressure are measured, after which a glucose solution is administered intravenously. If your health worsens, the measurements are repeated. If there are no characteristic symptoms, the analysis is repeated.

- Scintigraphy is a procedure that allows you to determine the rate of gastric emptying.

The diagnostic center of the Medscan clinic is equipped with modern expert-level equipment. We offer our patients a wide range of laboratory and instrumental examinations.

Why is it developing?

In the development of dumping syndrome, the leading role belongs to the rapid evacuation of food through what remains of the stomach, and the equally rapid filling of the jejunum with unprocessed food. Reflex signals from the jejunum swollen with food cause blood flow to the internal organs; on the periphery, the volume of circulating blood, on the contrary, decreases. The internal organs do not need blood in large quantities at all, so it is deposited, while the brain experiences real starvation.

Nutrients that enter the intestine without prior proper processing pass through the membranes of mucosal cells into the blood. In the experiment, stretching of the jejunum leads to the release of biologically active substances into the blood, mainly the “joy hormone” serotonin and acetylcholine. Hence weakness, palpitations, redness of the face and sweating, fluctuations in blood pressure.

An increase in the level of adrenaline secreted by the adrenal glands was detected, and the process of its secretion is triggered by the pituitary gland, which received information from the enterochromatophyte cells of the mucous membrane of the small intestine. These cells also stimulate the vomiting center of the brain. Stretching the intestine causes peristalsis - contraction of the intestines, which results in diarrhea, in which fluid, proteins and microelements are lost, which aggravates weakness and decreased blood pressure.

Rapid absorption of glucose in the jejunum disrupts metabolic processes in the pancreas, which releases more insulin into the blood than necessary. The concentration of sugar in the blood decreases below normal levels, which is also accompanied by severe weakness, hunger, and trembling. This mechanism is associated with delayed dumping syndrome, which develops a couple of hours after eating. Each patient develops all these pathophysiological changes to varying degrees, which ultimately lead to a decrease in the patient’s already low weight, the development of anemia and vitamin deficiencies, and most importantly, an uncomfortable life.

About prognosis and preventive measures

Medical practice shows that the development of the syndrome usually occurs in the first postoperative six months.

In half of the patients it weakens over time, in another quarter it remains at a certain level and does not develop, in the last twenty-five percent it is the opposite.

Preventive measures are based on systematic observation by a specialist, diet, and spa treatment.

The Onco.Rehab integrative oncology clinic operates using international treatment protocols. We do everything to keep our patients healthy!

I.V. Fedorov

GBOU DPO "Kazan State Medical Academy" Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Kazan

Fedorov Igor Vladimirovich - Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor of the Department of Endoscopy, General and Endoscopic Surgery

420012, Kazan, st. Mushtari, 11, tel., e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You must have JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract. The lecture describes the etiology, diagnosis, prevention and treatment of such post-gastroresection complications as dumping syndrome, post-vagotomy diarrhea, alkaline reflux gastritis, afferent and efferent loop syndromes, gastric atony, Ru-syndrome, relapse of peptic ulcer, gastric stump cancer and small stomach syndrome. stomach stump.

Key words: post-gastroresection syndrome, dumping syndrome, gastric stump cancer.

Any operations on the stomach, especially those accompanied by removal or disconnection of the pylorus, especially with concomitant vagotomy, can be accompanied by serious disturbances of gastric motility. Such disorders are very common, but adaptation usually occurs 6 months after surgery. A small but significant number of patients continue to suffer from these symptoms, which significantly compromises their health. The combination of these symptoms is called post-gastroresection (PGRS) or post-gastrectomy. These include dumping, alkaline reflux gastritis, post-vagotomy diarrhea, Roux syndrome, afferent loop obstruction, chronic gastric atony, and small gastric stump syndrome. These symptoms are associated with either faster or slower emptying of the gastric stump. Other late complications—ulcer recurrence, gastric stump cancer, malabsorption—are not directly related to motility disorders.

Dumping syndrome

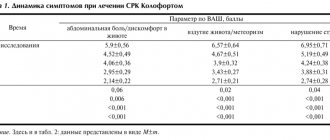

Dumping syndrome (DS) is one of the most common causes of pain after gastric surgery. Symptoms develop after eating, but the person is completely healthy on an empty stomach. The syndrome is characterized by gastrointestinal and vasomotor manifestations. Gastrointestinal symptoms include abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting, and profuse diarrhea. Vasomotor symptoms are characterized by profuse sweating, dizziness, palpitations, weakness and a great desire to lie down. The severity of DS is highly variable and depends on the type of surgery. In general, this condition is experienced by 25-50% of patients after gastric surgery, but in only 1-5% it occurs in a severe, crippling form. Severe symptoms occur in 3-5% of patients after selective proximal vagotomy (SPV), in 6-14% after truncal vagotomy (STV) with drainage, and in 14-20% after gastrectomy.

DS is divided into early and late, depending on the time of onset of clinical symptoms. Early dumping starts 10-30 minutes after eating. Patients experience vasomotor and gastrointestinal symptoms. Late dumping begins 2-3 hours after eating and manifests itself only in the form of vasomotor symptoms. Approximately 75% of patients experience early and 25% late dumping, with a small number suffering from both. Symptoms usually appear in the first weeks after surgery, when the patient returns to a normal diet. Liquid and hydrocarbon foods are poorly tolerated. Some patients lose weight due to fear of food.

It is widely believed that DS is associated with rapid gastric emptying. This is due to four surgical factors: decreased adaptation and receptive relaxation that accompanies vagotomy; decrease in stomach volume as a result of organ resection; decreased control of emptying due to removal or disconnection of the pylorus; elimination of the feedback mechanism when the duodenum is disconnected. Special studies have shown that DS in a healthy person is provoked by the rapid administration of glucose directly into the duodenum or jejunum. The introduction of hyperosmolar chyme into the jejunum leads to the movement of a large amount of fluid from the bloodstream into the intestinal lumen. As the small intestine expands, contractions increase in amplitude and frequency, causing gastrointestinal symptoms. Sequestration of fluid leads to hypovolemia, which provokes vasomotor manifestations.

However, there is evidence that it is not only gastric emptying that is responsible for DS. Not all researchers confirm a direct connection between this complication and the rate of gastric emptying.

Hypovolemia is accompanied by an increase in heart rate, tachycardia occurs in patients with early DS. This leads to peripheral vasoconstriction. Although some studies demonstrate vasodilation, for example, an increase in blood filling of the mesenteric arteries after provocation of DS. Organ vasodilation and blood pooling may be an additional factor aggravating vasomotor symptoms.

Humoral factors also play a role in the pathogenesis of early DS. These intestinal hormones include vasoactive intestinal peptide, pancreatic polypeptides, neurotensin, enteroglucagon, serotonin, peptide YY, motilin, insulinotropic peptide. However, a significant increase in the level of enteropeptides in the development of DS has not been fully proven.

Rapid gastric emptying also plays a role in the development of late DS. Rapid entry of food into the jejunum and absorption of glucose leads to hyperglycemia and a hyperinsulinemic response. This further leads to hypoglycemia 2-3 hours after eating.

Diagnosis of DS is based on medical history and provocation of symptoms by oral administration of glucose. A radioactive isotope study can be used to confirm accelerated evacuation of liquid and mushy food. Endoscopy and radiography help in identifying the anatomy and diagnosing other post-gastroresection symptoms.

For many patients, the severity of symptoms decreases over time. Diet selection is the basis of treatment. The patient should be taught to eat small meals - often and little by little, with a small amount of carbohydrates and a high level of protein. A dry diet with liquid intake half an hour after the main solid food often helps. Patients should consume fiber and limit fat, and choose complex carbohydrates (vegetables) over simple carbohydrates (sugar). If the symptoms are severe, the patient should lie down for half an hour or an hour after eating. Many patients intuitively come to this themselves.

Most patients cope with diet, but some require additional treatment. Supplementation with dietary fiber is effective because it delays absorption and prolongs intestinal transit time, although the palatability of these fibers is quite low. Osteotide, a somatostatin analogue, in the form of subcutaneous injections has been successfully used to treat early and late DS. It affects various parts of the pathogenesis of dumping. Delays the time of gastric emptying and intestinal transit, especially on an empty stomach, due to the blockade of intestinal peptides responsible for intestinal motility. Osteotide also blocks insulin release, glucose absorption and enteric secretion. Inhibits vasodilation of peripheral vessels caused by food intake. The long-term complications of osteotide are unknown.

For the surgical treatment of DS, complex operations have been proposed, such as reconstruction of the pylorus, narrowing of the gastrojejunostomy, transfer of the anastomosis according to B-II to B-I (reduodenization), small intestinal interposition, reconstruction of the anastomosis according to Roux. Although initial success is possible, long-term results are disappointing. Surgery is a last resort in patients with severe DS that is resistant to diet and drug treatment.

In patients who have previously undergone pyloroplasty, reconstruction of the pylorus is quite possible. The continuity of the pyloric ring is restored by bringing together the previously crossed muscle fibers. This procedure is simple and harmless, but the success rate is highly variable. Anastomotic narrowing is quite understandable as a concept, but is rarely successful. It is difficult to judge in advance the size of the stoma, which will prevent DS, but will not lead to persistent disruption of gastric evacuation. In addition, over time, stricture or stretching of the anastomosis may occur. Transferring the anastomosis from B-II to B-I restores duodenal passage, is rarely accompanied by complications and leads to an alleviation of symptoms in approximately 75% of patients. However, in 25%, for unknown reasons, improvement does not occur. Many types of jejunal interposition have been described—isoperistaltic and antiperistaltic. The most effective is a 10 cm antiperistaltic jejunal segment, which can be located between the stomach and duodenum, in the outlet loop of the gastroenteroanastomosis or Roux-en-anastomosis. Some authors provide good results, while others describe severe disturbances in gastric emptying. For patients suffering from DS after gastric resection according to B-I or B-II, reconstruction with a cY-shaped anastomosis according to Roux gives a more lasting result. The intersection of the jejunum during this operation creates an ectopic pacemaker, inducing retrograde contractions, complicating the transit of chyme and slowing down gastric emptying. However, this procedure can lead to the development of Roux syndrome (see below).

Post-vagotomy diarrhea

Although diarrhea is not specific to gastric surgery, it is more likely to occur in patients who have undergone vagotomy. The incidence of diarrhea after truncal vagotomy is 20%, after selective vagotomy - 5%, and after PPV - 4%. Symptoms are characterized by frequent watery stools, often occurring at night, and are usually not associated with carbohydrate absorption. Attacks are observed periodically, lasting several days, then they do not recur for several months. Symptoms subside over the course of a year and are rarely detrimental.

The diagnosis of post-gastrotomy diarrhea is made clinically; it is important to distinguish it from other post-gastroresection symptoms, which may be accompanied by frequent loose stools. A complication of vagotomy should be differentiated from other causes of diarrhea, such as anaerobic infection, by performing specific diagnostic tests. Patients with persistent symptoms may require examination of the gastrointestinal tract: irrigoscopy, colonoscopy, endoscopy with a biopsy of the small intestinal mucosa to exclude other causes of stool disorder.

The pathophysiology of post-vagotomy diarrhea is multifactorial. Rapid gastric emptying is often accompanied by diarrhea, but surgical correction does not solve the problem. Accelerated movement of chyme often leads to malabsorption of nutrients. When vagotomy is performed more selectively, the incidence of diarrhea decreases, supporting the concept that its cause is vagal denervation of the small intestine and biliary tract, loss of external control of gastrointestinal motility.

Drug treatment of diarrhea is similar to DS; diet is of primary importance. Antidiarrheal drugs such as loperamide, diphenoxylate and opiates are useful. Cholestyramine is very effective. If these measures fail, osteocide is prescribed.

The surgical route should be reserved for a small number of patients with chronic debilitating symptoms unresponsive to other measures. As discussed previously, although rapid gastric emptying is correlated with diarrhea, surgery does not provide improvement. The strategy, therefore, is to slow the passage through the small intestine. The most commonly used 10-15 cm antiperistaltic segment of the jejunum is located 100 cm distal to the gastrojejunostomy or the ligament of Treitz. However, the results of this operation vary.

Alkaline reflux gastritis

Alkaline reflux gastritis develops in 5-15% of patients undergoing gastric surgery. Symptoms include burning pain in the epigastrium, which is stopped by taking antacids, they intensify after eating or in a horizontal position of the body, and are accompanied by nausea and bilious vomiting. To reduce symptoms, patients often restrict themselves from eating, which leads to weight loss and anemia. Alkaline reflux gastritis requires surgical treatment more often than other PGRS.

The pathogenesis of the symptoms is that the biliary intestinal contents come into contact with the gastric mucosa after the pylorus has been destroyed, disconnected or resected. The incidence of complications is higher after gastric resection according to B-II than according to B-I, or after truncal vagotomy with drainage. After PPV, reflux is not observed. The amount of reflux correlates with the severity of symptoms.

The diagnosis of alkaline reflux gastritis is made by exclusion. Recurrent ulcers, gastroparesis, afferent or efferent loop syndrome, pancreatic and gallbladder diseases should be excluded. Gastroscopy with biopsy is the most common. It excludes recurrence of ulcers and afferent loop syndrome, which also cause bilious vomiting. Hyperemia and bile staining are typical for the gastric mucosa. Superficial gastritis and erosions affect the entire surface of the mucous stump of the stomach, but are more pronounced in the area of the lesser curvature. Histologically, a decrease in the number of parietal and main cells, a decrease in the number of cells producing mucin, ulceration and atrophy of the mucosa, signs of chronic inflammation of the gastric glands, distortion of their anatomy, and intestinal metaplasia are determined. However, the severity of symptoms does not correlate with changes in histological findings. X-ray of the stomach is not very informative; it only helps to clarify the postoperative anatomy and exclude other PGS, such as recurrent ulcers and obstruction.

Confirmation and quantification of gastric reflux can be assessed using a cholecystokinin scan. The patient is given a radioactive drug that accumulates in the liver and radioactivity is determined over the liver, gall bladder, biliary tract, small intestine and gastric stump. Additionally, the introduction of an alkaline solution into the stomach is used as a provocative test for the diagnosis and determination of reflux, and the selection of patients who are candidates for surgery. The test consists of introducing standard solutions of -0.1 NHCl and 0.1 NNaOH into the stomach. A positive response is considered to be the appearance of symptoms after the introduction of alkali, but not other solutions. Drug treatment is usually not effective. However, cholestyramine can be used to bind bile acids that cause gastritis. Antacids also bind bile acids and lysolecithin. Motility stimulants and antibiotics are ineffective.

The essence of surgical treatment is to divert duodenal contents from the gastric stump. The most commonly used Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy with a loop length of at least 45 cm. If vagotomy has not been performed previously, it should be performed during the application of a Y-shaped anastomosis to prevent the formation of anastomosis ulcer. Another alternative is the interposition of the isoperistaltic jejunal segment between the gastric stump and the small intestine. Operations give good immediate, but not always satisfactory long-term results. Epigastric pain recurs in 30% of patients, and nausea and vomiting in 50%.

A potential problem with these operations may be delayed gastric emptying of solid food - early satiety, epigastric pain, vomiting without bile. All this is defined as Ru-sindom, the development of which is most likely in patients with an initial delay in emptying. Therefore, preoperative study of the rate of gastric emptying is mandatory. Additional subtotal resection can speed up gastric emptying.

Adductor and efferent loop syndromes

This complication requires the presence of an afferent and efferent loop, and therefore occurs only after resection according to B-II or Roux. Any of the two symptoms - afferent and efferent loops - is caused by obstruction and is accompanied by the development of acute and complete or chronic partial obstruction. Adductor loop syndrome (ALS) is more common and is caused by anatomical factors. There are known cases of internal herniation, inversion of the loop and nodulation of the anastomosis. These complications are more often observed with an anterior-colic anastomosis or with a long adductor loop (more than 10-15 cm). Today, the symptom occurs after gastric resection with a frequency of 1%.

Acute obstruction of the afferent loop often leads to failure of the duodenal stump and requires emergency intervention. The complication appears in the first or second week after surgery. Bile and pancreatic juice accumulate inside the loop. As the pressure rises, obstruction of the bile and pancreatic ducts occurs with the possible development of necrosis of the small intestine. Patients complain of severe epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting. The amylase level increases, and necrosis of the adductor colon may be detected during surgery. If only the distal part of the loop is involved, it is resected with a Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Involvement of the duodenum in the horseshoe process requires pancreaticoduodenectomy. Volvulus may recur, so excess bowel must be resected. The retroanastomotic space and all mesenteric defects should be sutured to prevent recurrence of the hernia.

Chronic SPP is the result of partial bowel obstruction. Additional anatomical factors include stricture of the anastomosis, external compression by adhesions or tumor, recurrence of ulcers, tumor of the gastric stump, scarring of the opening in the mesocolon after retrocolic anastomosis, jejunogastric intussusception, although the latter condition is rare. Symptoms include nausea, pain in the right hypochondrium after eating, bilious vomiting, sometimes in a fountain, often without food, with rapid subsidence of pain after bowel movement. Patients consciously or unconsciously avoid food and lose weight.

A history is helpful in diagnosing SPP, but alkaline reflux gastritis is always present. CT and ultrasound are appropriate, but endoscopy remains the method of choice. It allows you to directly examine the anastomosis and take a biopsy. If the diagnosis is confirmed, surgery is indicated. The anastomosis according to B-II should be reconstructed into B-I or Roux.

Obstruction of the efferent loop is less common, usually as a result of the formation of a retroanastomotic hernia. Other causes are adhesions, fibrosis and jejunogastric intussusception. The syndrome can also have an acute or chronic form. I am concerned about cramping pain, nausea and vomiting - food with bile. The diagnosis is made radiographically with contrast retention at the level of the outflow loop obstruction. An operation is indicated, which consists of cutting adhesions, eliminating the hernia, covering the anatomical defect, revising the anastomosis or transferring it to B-I or Roux.

Chronic gastric atony and Ru-syndrome

Chronic gastric atony is characterized by nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, bloating after eating and the formation of bezoars. Patients cannot tolerate solid food, but accept liquid food, intuitively forming their diet. This complication is associated with a violation of the vagal innervation of the stomach, the frequency depends on the type of vagotomy performed previously. The likelihood of delayed gastric emptying is higher with less selective vagotomy. Since the peristaltic contractions of the antrum of the stomach and the tonic contraction of its proximal part in the late phase of gastric emptying are under the control of the vagus.

Evaluation of patients with chronic gastric atony begins with endoscopic exclusion of the mechanical nature of the obstruction. Scintigraphy confirms the delay in evacuation of solid food. Drug treatment involves the use of prokinetics. Permanent or temporary gastric decompression may be required. Prokinetics include bethanechol, metaclopramide, domperide, cisapride, erythromycin. Treatment is effective in 30-40% of patients. Surgical treatment consists of reducing the gastric reservoir, often in combination with Roux-en-Y resection with a 45 cm loop length.

Differential diagnosis of Ru-syndom and gastric atony is very difficult. The symptoms are similar. The possibility of independent existence of Ru-syndrome, regardless of gastric atony, is very problematic. However, the existence of Roux syndrome after total gastrectomy with esophagojejunostomy suggests that the Roux loop itself increases the risk of gastric atony. Transit along the Py-loop itself was studied scintigraphically, and a slowdown in transit along it was established. Both vagotomy and Roux-Loop slow gastric emptying, the incidence of evacuation disorders is 27-33%. Several factors further increase the likelihood of stasis: initial preoperative disruption of evacuation, large gastric stump, significant length of the Roux-loop. In the pathogenesis of Py-syndrome, the leading role is played by the disconnection of the Py-loop from the duodenal pacemaker with the appearance of retrograde peristaltic waves.

Treatment of patients with Ru-syndrome is similar to the tactics for gastric atony. It is important to eliminate mechanical obstacles. Gastric radiography and endoscopy help with this, and scintigraphy helps document chyme retention in the gastric stump, Roux loop, or both. Drug treatment is rarely successful. Surgical treatment consists of subtotal resection of the stomach and shortening of the Roux-loop to 40 cm; this operation ensures success in 70-80% of cases. It should be remembered that slowing gastric emptying using a Roux-loop may have a role in the treatment of DS, although clinical results are inconsistent.

Small gastric stump syndrome

This syndrome is characterized by rapid satiety, bloating in the epigastric region after eating and vomiting. The syndrome is associated with a decrease in the reservoir function of the stomach after its resection, vagotomy, or both operations. The condition develops more often after removal of more than 80% of the stomach volume. Symptoms are usually mild but usually lead to weight loss, malnutrition and anemia.

The diagnosis is based on the clinical picture, but mechanical obstruction must be excluded in every case. The diet consists of frequent split meals with the addition of vitamins, iron supplements, and pancreatic enzymes. Antispasmodics help some patients. Surgery is indicated for patients with severe symptoms resistant to diet and drug treatment. Surgical intervention consists of creating a reservoir from a duplicate of the small intestine, performed in various ways. The most common operations are "TannerRoux-19 pouch" or "Hunt-Lawrence". And although a favorable result can be obtained in 50% of cases, a significant number of complications in the form of stasis, dilatation, ulceration in the loop or reservoir dictate strict indications and understanding of the operation as a “measure of despair.”

Ulcer recurrence

Relapse occurs after primary surgical treatment of peptic ulcers of the stomach and duodenum. This pathology, together with reflux gastritis, is a leading cause of unsatisfactory results of gastric surgery. The most common symptoms of relapse are pain similar to primary peptic ulcer pain, which is observed in 80-95% of cases. However, it is difficult to distinguish from the pain that occurs with other PHS. Bleeding occurs in 40-60% of patients, which is 2 times more often than in non-operated patients with peptic ulcer disease. Bleeding is often hidden, but massive hemorrhages are not uncommon. Perforation of the ulcer is rare; a recurrent gastrojejunostomy ulcer can penetrate into the colon and cause the formation of a fistula. In this case, diarrhea, weight loss, and cloudy vomiting are observed, although the pain is usually not severe. The frequency of such ulcers is currently not high, but they can cause stenosis of the gastric outlet.

The first and most informative diagnostic test is endoscopy. A barium passage is necessary to study gastric emptying, although it is of little information for visualizing ulcers. Most ulcers have a diameter of 2 cm and are located in the area of gastroenteroanastomosis. The accuracy of endoscopy in their diagnosis is 90%. Most ulcers respond to traditional drug treatment.

The main reason for ulcer recurrence (60%) is inadequate or incorrectly performed primary surgery. Incomplete vagotomy is the most common cause, observed in 1/3 of cases. The anatomy of the vagus is highly variable and 12% of the population has more than two trunks. Most of the parasympathetic nerve fibers found during reoperation are found to the right of the esophagus or in the posterior paraesophageal space, as well as in the area of the angle of His - the criminal branches of Grassi. In the past, the most common cause of recurrence was inadequate gastric resection, although today removal of part of the organ without vagotomy is rarely performed. Inadequate removal of the antrum mucosa, which in some cases extends 1 cm and further into the duodenum, may be the cause of “retained antrum syndrome” and relapse of the ulcer, although this situation is rare. The remaining antral mucosa continuously produces gastrin, which stimulates gastric secretion. Other rare causes of recurrent ulceration include G-cell hyperplasia, Zolliger-Ellison syndrome, foreign body ulcers, and cancer. Concomitant factors are recognized as ulcerogenic drugs, smoking, delayed gastric emptying, enterogastric reflux, bezoars and primary hyperparathyroidism.

Endoscopy, along with determining the level of calcium and gastrin in the blood serum, is the leading method in diagnosing recurrent ulcers. If a defect in the gastric mucosa is detected, a biopsy is indicated to rule out cancer. Examination of the duodenal mucosa helps detect remaining antral mucosa. Since patients with hyperparathyroidism constitute a risk group for peptic ulcer disease, determination of serum calcium levels is indicated in all patients with recurrent ulcers, as is determination of serum gastrin levels. A hormone concentration above 1000 pg/mL allows one to suspect Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, while a normal gastrin level excludes this disease. The fasting serum gastrin level in patients with retained antrum syndrome is usually 2-4 times higher than normal. Delayed gastric emptying indicates possible gastric obstruction or atony, which can lead to hypergastrinemia. In this case, the concentration of the hormone decreases after emptying the stomach.

Differential diagnosis for moderately elevated serum gastrin levels includes Zollinger-Elisson syndrome, retained antrum mucosa, post-vagotomy hypergastrinemia, and antral G-cell hyperplasia. Post-vagotomy hypergastrinemia is a moderate increase in the level of the hormone in the blood, less than 2 times, and is observed in 30-40% of patients after surgery. Antral G-cell hyperplasia, also called pseudo-Zollinger-Elison syndrome, is a rare condition characterized by hypergastrinemia and hypersecretion in the absence of gastrinoma. A provocative test with the administration of secretin is indicated for these patients. In patients with Zollinger-Elisson syndrome, injection of secretin leads to an increase in gastrin concentration by more than 100 pg/mL, which does not occur after vagotomy. In patients with ambiguous results of the secretin test, food stimulation is indicated. Standard protein meals increase gastrin concentrations among patients with retained antrum or G-cell hyperplasia.

If one of the diagnoses has been established, appropriate treatment is started. The remaining antrum mucosa is removed surgically. Antrumectomy is indicated for antral G-cell hyperplasia. The diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism requires parathyroidectomy. Treatment for stomach cancer depends on its stage. For Zolliger-Alison syndrome, it is necessary to determine whether surgery is indicated. Intervention is necessary in patients with a single non-metastatic gastrinoma when drug treatment is ineffective. Conservative treatment is appropriate in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasm syndrome and metastatic gastrinoma. The initial study will exclude the most rare causes of ulcer recurrence that require specific treatment. Most of the remaining cases are due to incomplete vagotomy and can often be treated with medication. A vagotomy completeness test is indicated when medications are ineffective and surgery is highly likely. The test helps in choosing the option of surgical intervention.

Several tests help measure gastric secretion. The first determines basal secretion, the subsequent - stimulated by gastrin and pentagastrin. To determine the completeness of vagotomy, the Hollander hypoglycemic test is used.

Drug treatment is indicated for patients with uncomplicated recurrent ulcers who do not have hypersecretion or impaired gastric emptying. Standard doses of H2 histamine receptor blockers cure 80% of recurrent ulcers. Maintenance therapy with H2 blockers is further indicated throughout life. Refusal to do so leads to rapid relapse. It is clear that taking ulcerogenic drugs, smoking and alcohol should be excluded.

Surgery is indicated if the relapse is not cured 3 months after the start of drug therapy; if the ulcer recurs within a year during maintenance therapy; when a peptic ulcer occurs with short remissions or without them at all; if the lifestyle cannot be considered healthy, or the patient is not able to carry out the conservative treatment recommended by the doctor. The nature of the initial operation and the general condition of the patient must be taken into account. All patients must undergo a vagotomy completeness test before surgery. Gastric emptying should also be examined in each patient.

If the test shows incomplete vagotomy with adequate evacuation, revagotomy is indicated. Many surgeons also recommend gastrectomy if it was not part of a previous operation. If motility disorder occurs, gastric resection should be complete, leaving a small stump. With concomitant alkaline reflux gastritis, reconstruction of the Roux-en-Y anastomosis is optimal.

Gastric stump cancer

It is well known that gastric surgery for benign disease increases the risk of developing gastric cancer in the future. The latent period usually exceeds 15 years. This applies to any operations on the stomach - both resection and vagotomy, however, more often this late complication is observed after resection according to B-II.

The most common symptoms are epigastric pain, fullness, vomiting, dysphagia, weight loss, bleeding, and obstruction. Because these symptoms are similar to recurrent ulcers or other PHS, diagnosis is difficult. Given the long latent period for gastric cancer, a tumor should be suspected when the nature of complaints changes or new gastrointestinal symptoms appear. Often the patient presents with nonspecific complaints and symptoms that initially respond to drug treatment. The diagnosis is made on the basis of endoscopy with biopsy. Surgical treatment is mandatory, but the results cannot be considered satisfactory, as, indeed, in patients with primary cancer of the previously unoperated stomach.