Opportunistic infections, including mycoses, represent a pressing problem in modern medicine. Paradoxically, it was precisely the achievements of science that ensured the success of clinical medicine that led to an increase in the number of patients with opportunistic mycoses. In particular, advances in the treatment of a number of oncological and autoimmune diseases (the use of chemotherapy, anti-cytokine therapy, glucocorticosteroids and immunosuppressants) are associated with the emergence of a population of patients with acute and chronic iatrogenic immunodeficiency states. In turn, immunodeficiencies and local disorders of antimicrobial resistance in humans are the basis for the development of opportunistic mycoses, primarily candidiasis. Diagnosis and treatment of candidiasis of the mucous membranes of the digestive tract in some cases are associated with significant difficulties.

Fungi (Latin fungus, Greek mykes) are an independent vast kingdom of eukaryotic microorganisms, including about 90 thousand studied species. Until the end of the 1960s. Fungi were mistakenly classified as members of the plant kingdom. Among fungi, macromycetes and micromycetes are distinguished. The former are visible with the naked eye, the latter - with the help of microscopes. Unicellular (lower fungi, for example, Mucor) and multicellular (higher fungi, for example, Penicillium) forms of micromycetes are known [1].

Yeast-like fungi of the genus Candida are single-celled microorganisms 6–10 microns in size. These micromycetes are dimorphic: under different conditions they form both blastomycetes (bud cells) and pseudomycelia (threads of elongated cells). This morphological feature has, as will be shown below, important clinical significance.

Micromycetes of the genus Candida are characterized by ubiquity - widespread occurrence in the environment. Viable cells of Candida spp. can be found in soil, drinking water, food products, on the skin and mucous membranes of humans and animals. Thus, contact with these micromycetes of a person’s “open systems,” i.e., his skin and mucous membranes, is an ordinary fact.

Antifungal resistance

The outcome of contact with yeast-like fungi of the genus Candida is determined by the state of the human antifungal resistance system. In most cases, such contact represents a transient candidal carriage, when the structures and mechanisms of antifungal resistance ensure spontaneous decontamination of the human body. At the same time, in persons with disturbances in the antifungal resistance system, contact can form both persistent carriage and candidiasis. Thus, candidiasis of the digestive tract has typical features of an opportunistic infection. The disease of candidiasis of the mucous membranes is predetermined by the presence of the so-called fungi of the genus Candida. pathogenicity factors.

In particular, fungal cells can attach to epithelial cells (adhesion), and then, through transformation into a filamentous form (pseudomycelium), penetrate the mucous membrane, even “closed” systems (invasion), and cause necrosis of the tissues of the macroorganism due to the secretion of enzymes - aspartyl proteinases and fospholipases . The listed pathogenicity factors are naturally counteracted by numerous factors of antifungal resistance. In particular, the integrity of the epithelial layer of the digestive tract and mucopolysaccharides are of great importance. The protective role is played by the antagonism of yeast-like fungi and obligate bacteria of the digestive tract, the activity of digestive enzymes and the fungistatic effect of nonspecific humoral factors, such as lysozyme, complement, secretory IgA, transferrin, lactoferrin, etc.

However, the function of phagocytic cells, primarily polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and to a lesser extent, mononuclear phagocytes and natural killer cells, is of decisive importance in the system of antifungal resistance. The specific antifungal humoral response is realized due to the synthesis by B cells of specific anti-candidal antibodies of the classes IgA, IgM, IgG and, to a certain extent, IgE. Finally, the complex cooperation of dendritic and other antigen-presenting cells, helper types 1 and 2, and regulatory cells ensures an adequate specific immune response.

How is the disease diagnosed?

Visual methods for diagnosing candidiasis. Upon examination, inflammation of areas of the skin is revealed, limited to a border of exfoliating, macerated epidermis, and a whitish coating on the mucous membranes.

Laboratory diagnostics. Contrary to popular belief, the main method for diagnosing candidiasis is still microscopy of a smear from the affected areas of the mucosa. PCR (DNA diagnostics), which has become popular recently, is usually poorly suited for diagnosing candidiasis.

Laboratory diagnosis of the disease includes:

- microscopy of discharge smear

- cultural diagnostics (seeding)

- enzyme immunoassay (ELISA)

- polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Risk factors for mucosal candidiasis

Defects in the antifungal resistance system briefly described above are factors contributing to the occurrence of candidiasis, or so-called. risk factors. Risk groups for the development of candidiasis of the digestive tract are presented below: • physiological immunodeficiencies (early childhood, old age, pregnancy); • genetically determined immunodeficiencies (for example, selective IgA deficiency); • iatrogenic immunodeficiencies – (for example, the consequences of treatment with glucocorticosteroids, immunosuppressants, anticytokine, radiation and polychemotherapy); • diseases of the endocrine system (for example, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome, hypothyroidism); • dysbiosis of mucous membranes after antibiotic therapy; • AIDS; • chronic “debilitating” diseases (for example, cirrhosis of the liver); • nutritional status disorders (for example, starvation and vitamin deficiencies).

In these groups, candidiasis is detected more often than usual. Note that sometimes the clear cause of the violation of antifungal resistance cannot be determined.

What is esophageal candidiasis?

This is a disease that is caused by infection with fungi of the genus Candida. Infectious fungal infections of internal organs, mucous membranes and skin are dangerous and, if not properly treated, can lead to serious consequences and, in some cases, death. Therefore, it is unsafe to postpone a visit to the doctor if symptoms of esophageal candidiasis are detected.

At the first signs of illness, be sure to contact the medical center and make an appointment with a gastroenterologist as soon as possible. NEOMED has qualified specialists who will help with your problem.

Pathogenesis, clinical picture and diagnosis

The development of candidiasis of the digestive tract is characterized by the sequential passage of fungi through the following stages: adhesion, invasion, candidemia and visceral lesions. At the first stage, micromycetes adhere to the epithelial cells of any part of the mucous membrane. Subsequently, defects in the resistance system allow micromycetes to penetrate (invade) the mucous membrane and underlying tissues through transformation into pseudomycelium. Cytopenia is a decisive factor that allows invading fungi to reach the vascular wall, destroy it and circulate in the vascular bed (this stage is called candidemia). In the absence of adequate therapy, candidemia leads to the formation of foci of invasive candidiasis in the visceral organs, more often in the liver and spleen, lungs, and central nervous system.

At first glance, it is paradoxical, but the introduction of fungi of the genus Candida is often observed in areas of the mucous membrane represented by multilayer epithelium (oral cavity, esophagus), and much less often this occurs in relation to single-layer epithelium (stomach, intestines).

In practice, the clinician has to deal primarily with candidiasis, the frequency of which in healthy individuals reaches 25% in the oral cavity, in the intestines - up to 65–80% and significantly exceeds the frequency of the disease. Esophageal candidiasis, for example, occurs in general patients in 1–2% of cases, in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus in 5–10%, and in patients with AIDS in 15–30% [2].

Symptoms of candidiasis are primarily characterized by the appearance of the so-called. thrush and irritation of the mucous membranes. Typical complaints are burning of the mucous membrane of the tongue and the oropharyngeal cavity, dys, odynophagia, retrosternal discomfort, but a latent course also occurs. Symptoms of esophageal candidiasis can disrupt the act of swallowing, which in turn leads to malnutrition and a significant decrease in quality of life.

The scope of examination for candidiasis of the digestive organs includes the study of anamnesis and clinical picture, assessment of routine clinical tests, endoscopic studies, mycological (cultural, morphological, serological) and immunological tests.

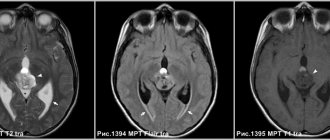

Endoscopic signs of candidiasis are hyperemia and contact vulnerability of the mucous membrane, as well as fibrinous deposits of various locations, configurations and sizes. The “standard” for diagnosing candidiasis of the mucous membranes is the detection of pseudomycelium of Candida spp. during morphological examination of biopsy specimens and scrapings.

In order to detect pseudomycelium, morphological mycological methods are used: cytological - with staining of smears according to Romanovsky-Giemsa, histological - with staining of biopsy specimens with the CHIC reaction.

Thus, taking into account the dimorphism of micromycetes Candida spp. is the key to the differential diagnosis between candidiasis and candidiasis. In modern conditions, the clinician must demand from the morphologist an accurate description of the morphological structures of the fungus, because the detection of individual yeast cells, as a rule, indicates candidiasis, and the detection of pseudomycelium allows confirming the diagnosis of candidiasis.

A disadvantage of morphological methods is their limited sensitivity for endoscopic biopsy. It is known that biopsy forceps make it possible to obtain a miniature fragment of tissue for study and the likelihood of detecting an informative sign with a single biopsy is insufficient.

The cultural mycological method is based on sowing biomaterials of mucous membranes on Sabouraud's medium. The advantage of this method is the possibility of species identification of fungi of the genus Candida and testing the culture for sensitivity to antimycotics. The relevance of such studies is due to

the fact that different species of Candida, in particular C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, C. glabrata, etc., have different sensitivities to modern antifungal drugs. Currently, modern laboratories have several diagnostic systems for determining the species of fungi and their sensitivity to antifungal drugs. Species identification and determination of sensitivity to antifungal drugs are based on the use of selective culture media, the study of the nature of sugar utilization by fungi and the enzyme profile of fungi, the dilution method, fluorescent hybridization, etc. (diagnostic systems Candiselect, Auxacolor, Fungiscreen, 60780 Fungitest, etc.). A cultural study of biomaterials of the mucous membranes with determination of the type of pathogen becomes strictly necessary in case of recurrent candidiasis or resistance to standard antimycotic therapy.

The disadvantage of the cultural method is the inability to differentiate candidiasis and candidiasis when studying materials from “open systems”, since mucous membranes can normally be contaminated with fungi of the genus Candida.

The sensitivity and specificity of serological tests for diagnosing esophageal candidiasis (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with Candida antigen, specific IgE level, Platelia latexagglutination test) have not yet reached the required accuracy, and their results should be assessed with some caution.

The management plan for patients with esophageal candidiasis must include diagnosis and correction of underlying diseases, other foci of candidal infection, rational antifungal therapy and immunocorrection.

In the clinic of the Scientific Research Institute of Medical Mycology of the St. Petersburg Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education, a patient with candidiasis must undergo a minimum amount of diagnostics of the alleged underlying disease, including: • clarification of the pharmacological history; • clinical blood test; • blood test for HIV infection; • blood test for glucose tolerance; • exclusion of the most common malignant tumors and, in connection with this, radiography of the lungs, fibrogastro, fibrocolonoscopy, additionally for men - ultrasound examination (ultrasound) of the prostate gland, additionally for women - ultrasound examination of the mammary glands and pelvis with consultation of a gynecologist.

Therapeutic measures

Treatment of mucosal candidiasis is based on the use of antifungal drugs. The general principle of action of all antifungal agents is inhibition of the biosynthesis of ergosterol in the cell wall of micromycetes. In general, antifungals used to treat candidiasis can be divided into three groups. The first is polyene antimycotics, which are practically non-resorbable when taken orally. These include amphotericin B, nystatin and natamycin. The second is azole antimycotics, which are relatively well absorbed when taken orally. These include: ketoconazole, fluconazole (most often prescribed for candidiasis), itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole. The third group is echinocandins: caspofungin, anidulafungin, micafungin.

The goal of treatment of candidiasis of the mucous membranes of the upper digestive tract is to eliminate symptoms and clinical laboratory signs of the disease, as well as to prevent relapses. A modern revision of the standards for the treatment of candidiasis of the mucous membranes of the upper digestive tract, published in the USA in 2009, contains fundamental changes and additions compared to a similar document of 2004 [3].

Most cases of oropharyngeal candidiasis and esophageal candidiasis are caused by C. albicans either as the only pathogen identified or as part of a mixed infection. However, cases of overt infection caused by species usually resistant to fluconazole, C. glabrata and C. krusei, are becoming increasingly common.

Numerous randomized prospective studies of the course of oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients with AIDS and cancer have been conducted in the USA and Europe; it was noted that the majority of patients respond to therapy with topical antimycotics. However, it has also been found that in patients with AIDS, relapses of candidiasis after therapy with locally acting antimycotics occur faster than after therapy with fluconazole, and resistance to antifungals can appear with all treatment regimens.

It is obvious that treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole in solution is more effective than treatment with ketoconazole and itraconazole capsules. For children aged 5 years and older, the recommended dose of itraconazole solution is 2.5 mg/kg twice daily, and the local effect of the solution may be as important as the systemic effect. In AIDS patients, posaconazole suspension is as effective as fluconazole therapy.

Recurrent candidiasis infection is typical for patients with immunodeficiency, especially for patients with AIDS. To prevent relapses of oropharyngeal candidiasis, long-term maintenance therapy with fluconazole is quite effective. It has been compared in efficacy to intermittent fluconazole in response to disease relapse, and long-term maintenance therapy has been shown to prevent relapse of candidiasis more effectively than intermittent therapy, but is associated with a greater risk of developing resistance.

At the same time, it has been shown that oral therapy with amphotericin B, nystatin and itraconazole capsules is less effective than treatment with fluconazole to prevent relapses of oropharyngeal candidiasis.

According to the recommendations, for the treatment of fluconazole-resistant candidiasis, an itraconazole solution should first be prescribed. It has been shown that at least 64, but not more than 80% of patients respond to such therapy. Posaconazole suspension is effective in approximately 74% of patients with recurrent oropharyngeal or esophageal candidiasis, and voriconazole may be effective in fluconazole-resistant candidiasis. Intravenously administered caspofungin, micafungin, and anidulafungin may be reasonable alternatives to triazole antimycotics. Oral or intravenous amphotericin B may also be effective in some patients.

Immunomodulation with the addition of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interferon gamma preparations may be useful in recurrent oral candidiasis.

The simultaneous detection of oropharyngeal candidiasis and dysphagia or odynophagia may indicate that the patient has esophageal candidiasis. A trial of fluconazole treatment for such patients with suspected esophageal candidiasis may be a cost-effective alternative to endoscopic examination: most patients with esophageal candidiasis report resolution of complaints within 7 days of starting therapy. In the treatment of esophageal candidiasis, fluconazole is more effective than ketoconazole, itraconazole capsules and flucytosine, and itraconazole solution is comparable in effectiveness to fluconazole. Up to 80% of patients with fluconazole-resistant candidiasis respond to treatment with itraconazole solution. Voriconazole is as effective as fluconazole and is superior in the treatment of fluconazole-resistant candidiasis, although it is associated with more side effects.

The use of echinocandins is characterized by a higher frequency of relapses of candidiasis than after treatment with fluconazole. Fluconazole-resistant candidiasis responds to caspofungin, which has similar efficacy to micafungin and anidulafungin. In patients with AIDS, candidiasis usually becomes recurrent, and long-term maintenance therapy with fluconazole is effective in preventing relapses. In HIV-infected patients, the use of HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) is associated with a decrease in the degree of contamination of the mucous membranes with C. albicans fungi and a decrease in the incidence of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Thus, HAART should be used as adjunctive therapy (to the extent possible) in all HIV-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis and esophageal candidiasis.

Chronic candidiasis of the skin and mucous membranes is a rare disease characterized by chronic persistent onychomycosis and damage to the mucous membranes caused by fungi of the genus Candida. Some of these patients suffer from thymoma or autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1. These patients should be given fluconazole as initial therapy. When widespread skin and nail lesions are present, the response to antifungal therapy may be delayed and relapse almost always occurs. Thus, most patients require chronic maintenance antifungal therapy. The development of fluconazole-resistant candidiasis is common. Patients with this form of the disease should be treated with the same therapeutic regimens that are used for fluconazole resistance in AIDS patients.

Treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis For the treatment of mild cases: irrigation with a solution of clotrimazole at a dose of 10 mg 5 times a day or a suspension of nystatin locally at a concentration of 100 thousand units/ml at a dose of 4-6 ml 4 times a day, or 1-2 lozenges with nystatin ( 200 thousand units each), prescribed 4 times a day for 7–14 days. Note that in the Russian Federation, dosage forms of nystatin in the form of suspensions or lozenges are not registered.

For the treatment of moderate to severe cases of the disease: oral fluconazole 100–200 mg (3 mg/kg) per day for 7–14 days.

For the treatment of fluconazole-resistant forms of the disease: either itraconazole solution at a dose of 200 mg/day or posaconazole suspension at a dose of 400 mg 400 mg twice daily for the first 3 days, and then 400 mg daily for up to 28 days. If these measures fail, voriconazole 200 mg twice daily or 1 ml of amphotericin B oral suspension given at a dose of 100 mg/ml 4 times daily is recommended. Please note that dosage forms of amphotericin B in the form of an oral suspension are not registered in the Russian Federation.

In case of refractory disease, echinocandins or intravenous amphotericin B at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg per day are also recommended. Chronic maintenance therapy is usually necessary for people with AIDS. In these cases, fluconazole is recommended at a dose of 100 mg 3 times a week. HAART is also recommended to prevent recurrence of infection.

For the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis associated with dentures, in addition to antifungal therapy, it is recommended to disinfect dentures.

Treatment of esophageal candidiasis

In all cases, treatment with systemically acting antimycotics is required. Local antifungal drugs (nystatin, natamycin, clotrimazole) are not effective. Oral fluconazole is recommended at a dose of 200–400 mg (3–6 mg/kg) per day for 14–21 days. For patients who cannot take oral medications, intravenous fluconazole 400 mg (6 mg/kg) per day or amphotericin B 0.3–0.7 mg/kg per day or echinocandins are recommended. It is acceptable to prescribe a diagnostic trial of antifungal therapy before performing an endoscopic examination (note that this recommendation is typical for the United States, where the cost of an endoscopic examination is significantly higher than the cost of a trial course of antifungal therapy).

For the treatment of fluconazole-resistant forms of the disease, the following are recommended: itraconazole solution at a dose of 200 mg/day, posaconazole suspension at a dose of 400 mg twice a day, or voriconazole 200 mg twice a day, prescribed intravenously or orally for a period of 14–21 days. Acceptable alternatives are micafungin 150 mg/day, or caspofungin 50 mg/day, or anidulafungin 200 mg/day, or amphotericin B 0.3–0.7 mg/kg/day.

For the treatment of recurrent esophageal candidiasis, fluconazole is recommended at a dose of 100–200 mg three times a week. HAART is recommended to prevent recurrence of infection in AIDS patients.

In general, the success of treatment of mucosal candidiasis depends not only on adequate antifungal therapy, but also on the success of correction of the underlying disease.

Treatment of candidal esophagitis

Candida under a microscope

Currently, there are many methods for treating various diseases. This disease is characterized by some difficulties in treatment. Sometimes the recovery process can take a long time, since not all methods are effective for one person.

It also sometimes happens that certain medications or procedures can lead to a number of serious side effects. Therefore, doctors approach the treatment of Candida esophagitis with great caution. Usually the patient is in the hospital under the supervision of a doctor. He is prescribed a number of medications, a special diet, and in severe cases, a hunger strike for several days.

Nutrition can also occur through a tube, but this is also in already complicated cases. The diet implies the exclusion of all foods that can damage the mucous membrane of the intestinal tract. These include alcohol, fatty foods, sweets, coffee, everything spicy and hot. In addition, cigarette lovers should give up their bad habit during treatment. For more effective treatment, sit on water for a couple of days or eat only fruits and vegetables.

Intestinal candidiasis. Symptoms

Disturbances of intestinal microbiocenosis with excessive growth of fungi of the genus Candida or candidal dysbacteriosis are clinically manifested by fermentative dyspepsia, abdominal pain, more in the sigmoid region, flatulence, frequent abundant foamy loose stools with mucus are noted up to 6-10 times a day, accompanied by disturbances in vitamin metabolism, low-grade fever fever, severe weakness, headache. Symptoms of damage to the mucous membranes in the form of stomatitis, glossitis, and vulvovaginal thrush are often observed. Fungal infection sharply reduces immunity, which leads to a deeper development of visceral candidomycosis with damage to the upper respiratory tract, lungs, genitourinary and digestive systems. In the blood - moderate leukocytosis, accelerated ESR, with sigmoidoscopy - catarrhal hemorrhagic proctosigmoiditis.

Indications for therapy are subject to clinical, microbiological, serological or histological confirmation of candidal infection, detection of candida with clinical manifestations from two or more surfaces of fungal colonization.

Intestinal candidiasis. Causes

It is generally accepted that the gastrointestinal tract is the main endogenous reservoir of Candida, from where the subsequent spread of infection throughout the body occurs. Candida albicans belongs to the opportunistic flora and is a component of the normal intestinal microflora. Determination of the presence of Candida albicans in 10x4 degrees in a bacteriological analysis of stool, according to official requirements, is not an indication for making a diagnosis of “intestinal candidiasis,” much less for antifungal therapy. In practice, the clinician has to deal with candidiasis, which is observed in the intestines up to 80% and it is better for Candida to be below the detection level in the analysis (0).

Risk factors for the development of candidiasis infection are varied, they are also caused by various diseases of organs and systems of the body, in which signs of impaired intestinal microflora develop, in particular diabetes mellitus, oncopathology, inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis), irritable bowel syndrome, anemia , AIDS, decreased immune defense, stress. Therapy for underlying diseases can also contribute to the development of intestinal microbiocenosis disorders and excessive growth of candida - this is the use of cytostatics, immunosuppressants, radiation therapy, antibiotics, and surgical interventions in the treatment.

The physiological periods of a person’s life, neonatality, pregnancy, menopause, old age, and deteriorating environmental conditions that reduce a person’s anti-infective resistance are also important in the occurrence of overgrowth of Candida fungi, which leads to an imbalance between the normal flora and the body’s immune response. (Burova S.A., Kurbatova I.V., 2006). All the reasons that were described above, in which a violation of the microbiocenosis of the gastrointestinal tract develops, can lead to candidiasis. The most significant conditions should be highlighted: gastric surgery, disorders of the secretory and motor functions of the stomach and intestines, colonic diverticulosis, and cirrhosis of the liver.

Poor nutrition and, in particular, steroids contained in food and supplements and food intolerance seem to be important for the development of dysbiosis of the gastrointestinal tract.