Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a group of tumors of the lymphatic system, which is based on the transformation of B lymphocytes into malignant cells.

- Causes and risk groups

- Symptoms of diffuse large cell B lymphoma

- Classification, forms and stages of diffuse lymphoma

- Diagnosis of diffuse large cell lymphoma

- Treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- Recovery after treatment for large cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Relapses of large cell lymphoma

- Complications of diffuse large B cell lymphoma

- Prognosis and prevention of large cell lymphoma

Causes and risk groups

The cause of DLBCL is a change in B lymphocytes, i.e., a violation of the DNA structure. Because of this, cells begin to grow and multiply uncontrollably, scattering throughout the body and affecting various organs and systems. Why these mutations occur has not been reliably established. Moreover, there are many people who have characteristic genetic defects but do not have lymphoma. This issue continues to be studied.

Currently, it is customary to talk about risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing this disease:

- Congenital and acquired immunodeficiencies: Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, Louis-Bart syndrome, AIDS, the need for treatment that reduces immunity: cytostatics, immunosuppressants during organ transplantation, etc.

- Viral infections: HIV, hepatitis C, T-lymphotropic virus.

- Autoimmune diseases: rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, etc.

- Toxic effects of insecticides, herbicides, benzene.

- Treatment through cytostatic and radiation therapy.

Signs and symptoms of BIA-ALCL

It is important to have a breast exam every day to monitor for any problems.

It is also important to maintain your follow-up appointment schedule with your plastic surgeon. At these appointments, the surgeon will check for signs of BIA-ALCL development.

The following are changes to the breasts or breast implants that may be signs of developing BIA-ALCL. These changes may occur in one or both breasts.

Contact your healthcare provider if you experience any of the following symptoms:

- Fluid around the implant. This can lead to breast enlargement or a feeling of tightness. This can happen many years after the implant surgery.

- Changes in the appearance of the breast. The breast may be swollen, lumpy, or appear misshapen.

- Tightness or scarring around the implant.

- Tumors on the skin or breast tissue. This is a less common symptom.

- Enlarged lymph nodes in the armpits (one or both). This is a less common symptom.

These signs do not always mean BIA-ALCL is present. These signs can also be caused by other problems, such as implant leakage. If any of these symptoms occur, make an appointment with your doctor.

to come back to the beginning

Symptoms of diffuse large cell B lymphoma

Large cell lymphoma can manifest itself with many symptoms, but all their diversity can be summarized into three syndromes:

- Enlarged lymph nodes - lymphadenopathy. Most often, lymphoma manifests itself as a painless enlargement of the lymph nodes, which can be detected visually or by palpation. But it happens that nodes that are inaccessible to inspection and palpation are affected (for example, in the chest or abdominal cavity), then this sign may not immediately appear.

- Symptoms of intoxication: fever not associated with infection, heavy sweating, weight loss. The combination of these signs is called B-symptoms. Its presence is important in determining the stage of the disease.

- Symptoms that develop when large cell lymphoma spreads to other organs and systems. This may include chest pain and cough, abdominal pain and bowel dysfunction. When the central nervous system is damaged, headaches, blurred vision and vomiting develop. Due to the destruction of bone marrow, immunity decreases, anemia develops and a tendency to dangerous bleeding.

Generalized lymphoma associated with HIV infection

Lymphomas are rare malignant lymphoproliferative diseases. In patients with HIV infection, mainly non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are detected, which are registered 200–600 times more often than in the general population and are classified as secondary diseases [1–4]. Based on histological characteristics, there are 5 types of NHL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primary exudative lymphoma, primary B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system, Burkitt's lymphoma and lymphogranulomatosis [2]. In the vast majority of cases, immunoblastic lymphoma is detected in patients with HIV infection with a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of less than 100 cells/μl, with a frequency of 3% [1, 2, 4, 5]. Immunosuppression and the presence of the Epstein–Barr virus, which is detected in 50–80% of patients, are important in the pathogenesis [2, 6–9]. The main symptom of lymphoma is enlarged, hardened, inactive and painless lymph nodes. Most patients experience fever, weakness, weight loss, and night sweats. Depending on the location of the process, there may be symptoms of organ damage (gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, liver, lungs, bones, etc.) [4]. Typically, the diagnosis is made at an advanced stage of lymphoma. The main diagnostic criterion is histological examination of a bone marrow or lymph node biopsy. The most common differential diagnosis is atypical tuberculosis [2, 4]. The oncological process in patients with HIV infection progresses rapidly. Specific highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in combination with chemotherapy in the early stages of the disease can have a certain positive effect. The development of primary lymphoma in patients who did not receive HAART indicates the most unfavorable prognosis for this pathology among all AIDS-defining diseases [2].

In Novokuznetsk, the incidence rate of HIV infection is 216.3 per 100 thousand population, the incidence rate is 1881 per 100 thousand population (according to official data for 2021). Every year, more than 400 adult patients with HIV infection are hospitalized in infectious diseases departments, mainly in the later stages of the disease. However, we observed only 4 cases of NHL.

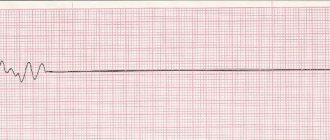

Case 1. Patient D., 41 years old (Fig. 1). She was admitted to the infectious diseases department on 04/07/15 with complaints of weakness, fever up to 39 °C, pain in the throat and neck. She fell ill on 03/25/15: fever, sore throat. On April 02, she went to the clinic, was examined by a therapist and an ENT doctor, and was sent to hospital with a diagnosis of lacunar tonsillitis, severe. Upon admission, she denied chronic diseases, drug use, and HIV status, and noted sore throats 1–2 times a year. The condition is of moderate severity, consciousness is clear, the position is active. T - 38.2 °C. The skin is pale pink and warm. The mucous membranes of the pharynx are clearly hyperemic; on the left, the tonsil is significantly increased in volume, almost completely covered with pus. Enlarged submandibular lymph nodes. The cervical lymph nodes on the left are enlarged to 2 cm in diameter and painful. The tongue is coated and moist. In the lungs and heart without significant pathology, blood pressure is 110/70 mm Hg. Art., pulse 74 beats/min, respiratory rate 18/min. The abdomen is soft, painless, the liver is at the edge of the costal arch, the spleen is not enlarged. In the hemogram from 08.04, ESR 80 mm/h, leukocytes 7.7 × 109, P 11, S 59, L 9, M 21, Tr 304 × 109, Er 2.8 × 1012, hemoglobin 80 g/l. Biochemical blood test showed bilirubin 11.0 µmol/l, AST 58 U/l, ALT 54 U/l, amylase 21 U/l, total protein 58 g/l, urea 5.7 mmol/l. A culture of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Streptococcus viridans was isolated from the throat. ECG: sinus tachycardia, without changes in the myocardium. The diagnostic search included examination for diphtheria, tularemia, and tuberculosis. Treatment: infusion therapy - 1250.0 ml/day, antibacterial therapy: Ampisid 3.0 × 3 times/day IV drops, symptomatic therapy, local treatment. From April 10, intensification of antibacterial therapy with gentamicin 80.0 × 3 times/day IM and doxycycline 1.0 × 2 times/day.

On April 10, it was revealed that the patient was HIV-infected; the diagnosis was established in 2010; in March 2015, the CD4+ level was 10 cells. He is not taking prescribed HAART. By 13.04, oropharyngeal candidiasis and cheilitis developed, which required the administration of fluconazole. The condition remained stable. Fever, lymphadenopathy, changes in the pharynx, and moderate diarrhea persisted. On April 15, the condition worsened and vomiting occurred up to 5 times. A sharp decrease in PTI was recorded - 17.1%, an increase in fibrinolysis (360 min), a decrease in total protein (47 g/l) and albumin (16 g/l) with normal ALT values (30.5 U/l) and a slight increase in AST (50.3 U/l). Hyponatremia (127.8), acid-base composition within normal limits (pH 7.43; PCO2 36.1; BE 0.1; SBC 24.1). Subsequently, despite treatment (transfusion of fresh frozen plasma, detoxification therapy, ceftriaxone 2.0 x 2 times/day i.v.), the severity of the condition worsened, multiple organ failure, ascites, and anemia increased. While the state of consciousness was preserved, on April 21, at 11:25 p.m., cardiac arrest occurred and death was pronounced.

During life, an examination was also carried out: chest x-ray (CH) dated April 15, without pathology. Ultrasound of the abdominal organs (ABP) dated April 16: liver +3 cm; no ascites or enlarged abdominal nodes were detected. The gallbladder, pancreas, spleen, kidneys are unchanged. Blood tests for sterility were repeatedly negative. Cytological examination of a smear from the tonsils dated April 17: a large amount of bacillary flora, squamous epithelial cells with nuclear degeneration; no atypical cells were found in the specimen. Sputum for pneumocystis from 16.04 negative. In the general blood test on April 20 and 21, hyperleukocytosis (22.6 × 109, 21.7 × 109), progressive anemia (Er 2.l × 1012), shift in leukocyte formula to promyelocytes and atypical cells, thrombocytopenia (l33 × 109), decreased hematocrit up to 0.19. Biochemical blood test dated April 20 without pathology. Prothrombin according to Quick 324.8, euglobulin fibrinolysis 360 min.

Post-mortem diagnosis: HIV infection, stage of secondary diseases IVB, progression phase. Severe sepsis. Multiple organ failure. Fungal infection of the gastrointestinal tract. Anemia of complex origin. Nephropathy. Lymphadenopathy. Tuberculosis of the lymph nodes? Edema, swelling of the brain. Pulmonary edema.

A postmortem examination revealed diffuse damage to internal organs (lungs, liver, spleen, heart, adrenal glands, kidneys) by cells of the lymphoblast type, lymphocyte-like with a large number of mitoses, including pathological ones. During a bacteriological examination of blood from the heart and spleen, a culture of KIebsiella pneumoniae was sown, which was regarded as evidence of the development of sepsis. The immediate cause of death was cerebral edema. Pathological diagnosis. Main: HIV-associated diffuse lymphoma with damage to the lungs, liver, spleen, heart, adrenal glands, kidneys. HIV-associated sepsis. Complications: hepatosplenomegaly. Severe dystrophic changes in all internal organs. Brain swelling.

This example demonstrates the difficulties of intravital diagnosis of lymphoma in HIV infection, the malignancy of the lymphoproliferative process with rapid progression in combination with sepsis and an unfavorable outcome.

Observation 2. Patient S., 32 years old, was admitted to the infectious diseases hospital on June 20, 2017 with complaints of weakness, facial asymmetry, and blurred vision. Got acutely ill on June 7: a dark spot appeared in front of the right eye, examined by an ophthalmologist, diagnosis: retinitis? After 3 days - numbness of the lower lip, the right half of the body, swelling of the right half of the face. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain dated 06/09/2017 revealed hyper- and isointense foci in the frontal and parietal lobes, subcortical nuclei of presumably vascular origin, and neck lymphadenopathy. From June 15, low-grade fever to 37.7 °C. 19.06 increased facial asymmetry. Life history: drug addiction, chronic hepatitis C and HIV infection since 2012, has been taking HAART since June 15, 2017. СD4 31 cells

Upon admission, the patient was in a moderate state of consciousness, adynamic. Symptoms of intoxication are determined. Hematomas on the skin, moderate hyperemia in the pharynx, coated tongue. Blood pressure 140/100 mm Hg. Art., heart rate 109. No pathology was detected in the internal organs; dubious meningeal symptoms, paresis of the upper and lower branches of the facial nerve on the right. HIV-associated encephalitis is suspected. The hemogram showed thrombocytopenia (47 × 109), anemia (Er 3.0 × 1012, Hb 74). Liquor: C - 783 cells, N - 93%, b - 1.65 g/l, Pandi 3+. On June 27, the condition worsened, hemorrhagic syndrome and tachycardia developed. Control lumbar puncture, cerebrospinal fluid: C - 1898, N - 94%, b - 0.66 g/l. On September 28, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was performed again: an isointense formation was additionally revealed in the right Meckel’s space, spreading along the tentorium of the cerebellum, up to 10 mm thick, pathologically accumulating contrast agent, the 7th pair of cranial nerves on the right was thickened to 5 mm. Conclusion: differentiate between lymphoma and meningioma. On June 29, the patient began to feel the urge to vomit; the stomach is distended, the stool is “melena”. During esophagogastroduodenoscopy, Mallory-Weiss syndrome, bleeding, acute gastric ulcers, erosive bulbitis and duodenitis were identified. Ultrasound ABP: hepatosplenomegaly, portal hypertension. X-ray of the OGK shows pneumonia on the left. In the hemogram Er 1.47 × 1012, Hb 49, Tr 20 × 109. In the evening of June 29, shortness of breath appeared up to 42/min, signs of acute renal failure: oliguria, increase in nitrogenous waste. On June 30, the condition was terminal, at 19.30 death was pronounced.

CSF examination: polymerase chain reaction for CMV, EBV, herpes negative, bac. sowing on m/fl., mushrooms - negative. Test for AFB of sputum, urine, feces - negative. Enzyme immunoassay blood test for toxoplasmosis (IgG+, IgM-), CMV (IgG+, IgM-), fungi (IgM-), syphilis - negative. Blood sterility and blood culture - negative.

Post-mortem diagnosis: HIV infection, stage of secondary diseases 1VB. HIV-associated meningitis of unspecified etiology. Lymphoma of the brain? A brain tumor? Complications: multiple organ failure.

Pathological diagnosis: HIV-associated generalized small cell lymphoma with damage to the brain, lungs, mediastinal lymph nodes, liver, kidneys, adrenal glands, spleen. Complications: tumor intoxication. Deep dystrophic changes in internal organs.

The case demonstrates the difficulties of intravital differential diagnosis of lymphoma with other lesions of the central nervous system in HIV infection, the rapid progression of the disease with generalization of the process, involvement of the central nervous system and an unfavorable outcome.

Case 3. Patient R., 45 years old (Fig. 2). She was in the infectious diseases department from October 23 to November 26, 2017 (34 days). Complaints upon admission: weakness, fever up to 38.5–40 °C, cough. HIV infection was detected in 2014, according to an immunogram, CD4 = 70 cells/μl (April 2017). She received HAART irregularly. Deterioration in health, fever noted for 2 months. X-ray of the chest cavity revealed a mass in the upper mediastinum, and the patient was sent to the hospital. History of drug addiction for many years, chronic hepatitis C, nodular goiter.

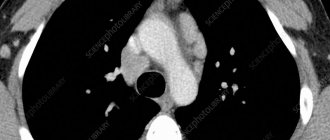

At the initial examination, the patient was in a moderate condition, conscious, in an active position. Reduced nutrition. The skin is pale pink, there are dense infiltrates of 4–5 cm on the legs, no fluctuations. Peripheral lymph nodes are not enlarged. In the lungs, the heart is without pathology, the liver is up to +3 cm below the costal arch. The dynamics showed periodic rises in temperature to 38.5–38.7 °C, enlargement of the liver and spleen. Changes in spiral computed tomography dated October 27, 2017: in the upper floor of the anterior mediastinum, from the level of the thoracic aperture, an additional pathological space-occupying formation of homogeneous density, with a relatively clear contour, 47.4 × 54.3 mm, is detected, displacing the trachea to the left. The group of paratracheal, paravascular, prevascular, hilar lymph nodes on both sides was increased to 16 mm along a short radius. Pneumofibrosis. Conclusion: space-occupying lesion of the anterior mediastinum. Differentiate with lymphoma, thyroid goiter, lipoma.

Since 07.11, the condition has worsened, abdominal pain, swelling of the lower extremities, the anterior abdominal wall, increased abdominal volume, decreased diuresis. In a biochemical blood test, an increase in creatinine (246.7–334.3 µmol/l) and urea (25.4 mmol/l), metabolic acidosis, according to ultrasound, ABP - hepatosplenomegaly, ascites (07.11.2017), hydronephrosis on the right (11.11. 2017). Chronic virus-associated glomerulonephritis and chronic renal failure are suspected. Subsequently, gradual negative dynamics: an increase in edema spreading to the face and hands, progression of renal failure (blood urea 30.18 mmol/l, creatinine 376.6 µmol/l), from November 23rd, the onset of respiratory failure, which led to death on November 26th.

General blood test dated November 2, 2017: ESR 60, Hb 80 g/l, Er 2.6 units/l, L 4.5 units/l, e 1%, w 1%, p 17%, s 66%, lim 12%, mn 3%, tr 114.0 u/l, hematocrit 0.23; from November 24, 2017, the reduction in TP was 21.0 units/l. Multiple blood tests for sterility, fungi - negative, sputum testing (10/24/2017 - pneumococcus 105 CFU/ml), urine, stool for BK - negative. In the immunogram dated October 25, 2017, CD4 = 7 cells/μl. Echocardiography without pathology. The patient received antibacterial, hormonal, antifungal, diuretic therapy, transfusions of fresh frozen plasma, red blood cells, and HAART.

Post-mortem diagnosis: HIV infection, stage IVB. HIV-associated sepsis. Mediastinal lymphoma cannot be excluded. Complications: multiple organ failure (hepatocellular, renal, respiratory, cytopenia). Congestive pneumonia. Pulmonary edema. Encephalopathy of complex origin. Brain swelling. Chronic viral hepatitis C. Nephropathy. Anemia, thrombocytopenia.

Pathological diagnosis. Main: HIV-associated diffuse large cell lymphoma with damage to the mediastinum, intrathoracic para-aortic lymph nodes, spleen, kidneys, pleura, peritoneum. Complications: pulmonary edema. Brain swelling. Severe dystrophic changes in internal organs. Associated: chronic viral hepatitis C. Conclusion: a postmortem examination of a patient suffering from HIV infection revealed diffuse damage to internal organs (spleen, kidneys, intrathoracic and para-aortic lymph nodes, pleura, peritoneum, mediastinum) by large lymphocyte-like cells with a large number of mitoses, including pathological ones.

In this case, a mediastinal mass (presumably lymphoma) was discovered 1 month before the patient's death. The diagnosis of diffuse lymphoma and specific damage to other organs and systems were established only during a pathological examination.

Case 4. Patient S., 30 years old (Fig. 3). Hospitalized in the infectious diseases department on September 28, 2017 for HIV infection stage IVB, progression phase, bilateral polysegmental pneumonia, with complaints of fever, shortness of breath, cough, weakness. Since September 24, 2017, fever, shortness of breath. According to radiography of the OGK on September 28, 2017, bilateral polysegmental pneumonia. Progression of the underlying disease? Associated with an opportunistic infection (pneumocystis, tuberculosis)? From the medical history it is known that HIV infection was detected in 2021 and he is receiving HAART. CD4 = 400 cells (examined in September 2021). Drug addiction for many years, the last time I used drugs was in June 2021. Chronic hepatitis C without biochemical activity was diagnosed. Since April 2021, enlarged lymph nodes in the neck on the right appeared, fever up to 39.6 °C. He was examined at the oncology clinic; based on the results of histological examination, a diagnosis of stage 3 large B-cell lymphoma with damage to peripheral lymph nodes was established; 3 courses of chemotherapy (doxorubicin, vincristine, rituximab) were administered.

Upon admission, the patient was in a serious condition due to intoxication, conscious, and in an active position. Satisfactory nutrition. The skin is flesh-colored. The face is asymmetrical, enlargement and deformation of the neck on the right (photo), tumor with a diameter of 12–15 cm (conglomerate of lymph nodes, swelling of soft tissues). There is no swelling. Breathing is harsh, 24/min, dry rales throughout all lung fields, wet rales on the right. Blood pressure 100/60 mm Hg. Art., heart sounds are clear, rhythmic, heart rate 100/min. The abdomen is soft, painless, the liver is 3.5–4 cm below the costal arch, dense. The spleen is at the edge of the ribs. In the hemogram, ESR is 52 mm/hour, Er 3.5 × 1012, L 9.9 × 109, basophils 2%, eosinophils 4%, blasts 26%, promyelocytes 2%, myelocytes 2%, young 4%, band 4%, segmented 2%, lymphocytes 42%, monocytes 14%, platelets 94.5 × 109. A biochemical blood test revealed an increase in liver enzymes (ALT/AST - 73.7/136.1 U/l), nitrogenous waste (urea 14, 08 mmol/l, creatinine 146.6 µmol/l), decreased glucose (2.91 mmol/l). According to the results of a study of the acid-base state of venous blood - metabolic disorders: pH 7.394, PCO2 29.1↓, PO2 36↓↓, BEb -6.2, BEecf -7.3,%SO2 with 69.9%. Spiral computed tomography of the OGK from 05.10.2017. Diffusely throughout the pulmonary fields of both lungs, symmetrically, more in the hilar zone, an alveolar lesion is detected in the form of a spotty, ground glass-type compaction, with partial preservation of the subpleural areas of the lungs. Additionally, single hyperdense lesions of different sizes ranging from 3 to 12 mm in size are detected in both lungs. Lymph nodes are enlarged to 12 mm. Conclusion: bilateral Pneumocystis pneumonia. Focal lesions of the lungs are differentiated from metastatic lesions, septic embolism, and focal tuberculosis. Tuberculosis was excluded upon consultation with a phthisiatrician. Detoxification, antibacterial (ceftriaxone, Hemomycin, Biseptol, co-trimoxazole), antifungal (fluconazole), and symptomatic therapy was carried out. 02.10 nosebleeds, subcutaneous hemorrhages on the forearms. Against the background of the ongoing therapy, since 09.10 there has been a positive trend, manifested in a decrease in intoxication, normalization of temperature, disappearance of shortness of breath, and improvement in the physical picture in the lungs. However, from 12.10 the fever returned to 38.1 °C, the cough with mucous sputum intensified, and multiple moist rales appeared in the lungs throughout all fields. On October 15, from 20:00, signs of respiratory failure began to increase; at 22:00, cardiac activity and breathing stopped. Resuscitation measures were not effective and death was pronounced.

Laboratory dynamics in the hemogram revealed a decrease in hemoglobin and platelets; in a biochemical analysis, along with the normalization of liver and kidney parameters, an increase in LDH to 1938.7 U/l. Reduction of prothrombin according to Quick to 57.2%. Pneumocystis were found in the sputum on September 29, and a culture of Candida albicans was isolated. Blood and urine cultures are negative.

Post-mortem diagnosis. HIV infection IVB-C, progression phase. Pneumocystis pneumonia, severe. Stage 3 large B cell lymphoma with involvement of peripheral lymph nodes. Complications: severe sepsis. Multiple organ failure. Endotoxic shock. Pulmonary edema. Encephalopathy of complex origin. Brain swelling. Nephropathy. Anemia of complex origin. Chronic viral heparitis. Background: drug addiction.

Pathological diagnosis. Main: HIV-associated diffuse B-cell lymphoma with damage to peripheral, intrathoracic, para-aortic lymph nodes, spleen, liver, kidneys, stomach wall. Complications: pulmonary edema. Brain swelling. Severe dystrophic changes in internal organs. Concomitant disease: drug addiction.

In the presented clinical case, the diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma was established during life, and active chemotherapy was carried out against the background of HAART. However, the progression of the cancer process could not be stopped.

conclusions

- It is advisable to include B-cell lymphoma in the differential diagnosis of opportunistic diseases in HIV infection.

- B-cell lymphoma usually develops in the later stages of HIV infection and has a rapidly progressive course with a pronounced intoxication syndrome and involvement of various organs and systems, including the brain.

- B-cell lymphoma in patients with HIV infection is often combined with other opportunistic diseases (in our observation, with Pneumocystis pneumonia, fungal infections) and concomitant pathology (chronic hepatitis C, drug addiction).

- When B-cell lymphoma is detected at a late stage of HIV infection, even during HAART and chemotherapy, the prognosis is unfavorable.

Literature

- HIV infection and AIDS: national guidance / Ed. acad. RAMS V.V. Pokrovsky. M.: GEOTAR-Media. 2013. 608 p.

- Bartlett J., Gallant J., Pham P. Clinical aspects of HIV infection. 2012. M.: R. Valenm. 2012. 528 p.

- Pokrovsky V. V., Yurin O. G., Kravchenko A. V., Belyaeva V. V., Ermak T. N., Kanestri V. G., Shakhgildyan V. I., Kozyrina N. V., Buravtsova V. V., Narsia R. S., Khokhlova O. N., Pokrovskaya A. V., Efremova O. S., Konnov V. V., Kuimova U. A., Popova A. A. National recommendations for dispensary observation and treatment of patients with HIV infection. Clinical protocol // Epidemiology and infectious diseases. 2015. No. 6 (Appendix).

- Pivnik A. V., Tumanova M. V., Seregin N. V., Parkhomenko Yu. G., Tishkevich O. A., Kovrigina A. M., Likunov E. B. Lymphomas in HIV-infected patients: a review of the literature // Clinical oncohematology. Reviews. 2014. T. 7. No. 3.

- Pokrovsky V.I., Lobzin Yu.V., Volzhanin V.M., Belozerov E.S., Bulankov Yu.I. Infections of the nervous system with a progressive course. St. Petersburg: Foliant Publishing House LLC, 2007. 264 p.

- Goreiko T.V., Kalinina N.M., Drygina L.B. Modern ideas about the immunopathogenesis of infection caused by the Epstein–Barr virus // Infection and Immunity. 2011. T. 1. No. 2. P. 121–130.

- Pagano JS Viruses and lymphomas // N. Eng. J. Med. 2002. Vol. 347. No. 2. P. 78–79.

- Shakhgildyan V. I., Yadrikhinskaya M. S., Safonova A. P., Domonova E. A., Shipulina O. Yu., Alvarez-Figueroa M. V., Dolgova E. A., Tishkevich O. A. Structure secondary diseases and modern approaches to their laboratory diagnosis in patients with HIV infection // Epidemiology and infectious diseases. Current issues. 2015. No. 1. pp. 24–30.

- Yachie A., Kanegane H., Kasahara Y. Epstein-Barr virus-associated T-/natural killer cell lymphoproliferative diseases // Semin. Hematol. 2003. Vol. 40. No. 2. P. 124–132.

Z. A. Khokhlova*, 1, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor R. A. Gileva* T. V. Sereda*, Candidate of Medical Sciences N. A. Nikolaeva*, Candidate of Medical Sciences A. P. Tishkina** L. Yu Zolotukhina*** Yu. M. Kirillova***

* NGIUV - branch of the Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Additional Professional Education RMANPO Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Novokuznetsk ** State Budgetary Institution of the Regional Clinical Hospital No. 8, Novokuznetsk *** State Budgetary Healthcare Institution of the Regional Clinical Hospital No. 29, Novokuznetsk

1 Contact information

Generalized lymphoma associated with HIV infection / Z. A. Khokhlova, R. A. Gileva, T. V. Sereda, N. A. Nikolaeva, A. P. Tishkina, L. Yu. Zolotukhina, Yu. M. Kirillova For citation: Attending physician No. 8/2018; Page numbers in the issue: 64-68 Tags: malignant lymphoproliferative diseases, skin, viruses, poor prognosis

Classification, forms and stages of diffuse lymphoma

The modern classification of large cell lymphoma is based on clinical data and the extent of the tumor process.

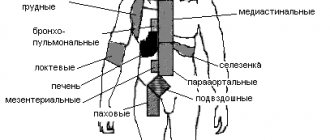

Ann Arbor classification:

- Stage 1. The lesion is limited to one lymphatic zone or one extralymphatic organ or one segment of extralymphatic tissue.

- Stage 2. Two or more areas of lymph nodes on one side of the diaphragm are affected. When extralymphatic organs or tissues are affected, metastases are detected in regional lymph nodes.

- Stage 3. There are single lesions on both sides of the diaphragm.

- Stage 4. There are multiple foci of damage to extralymphatic organs, or limited damage to extralymphatic organs with distant metastases, or damage to the liver and bone marrow.

The Ann Arbor classification is supplemented by the Cotswold modification:

- A - no B-symptoms.

- B - there is at least one of the B-symptoms.

- E - there are localized extranodal lesions.

- S - lymphoma has affected the spleen.

- X - there is massive tumor tissue and internal organs.

Diagnosis of diffuse large cell lymphoma

The diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is made on the basis of histological and immunohistochemical examination of tumor tissue. In order to obtain material, an incisional or excisional biopsy of the lymph nodes is performed. In addition, molecular genetic and immunophenotypic studies are performed, which will help determine the type of tumor, the presence of certain genetic changes and select the optimal treatment method.

To determine the stage of lymphoma, the following studies are performed:

- Trephine biopsy of bone marrow.

- Radiation diagnostic methods - ultrasound, CT, PET-CT, MRI.

- A number of laboratory tests are also prescribed - a complete blood count, determination of markers of parenteral hepatitis, HIV testing, biochemical studies, etc.

Diagnosis of the disease

According to the PROFILE registry, based on an analysis of 89 fully documented cases, the most common symptom of BIA-ALCL is periprosthetic seroma - in 73 (85.9%) patients. Capsular contracture occurred in 28 (32.9%) patients, most often grade III or IV. Palpable tumor masses in the mammary gland were detected only in 13 (15.7%) cases. Pain, skin breakdown, and redness were less common but still present. Systemic symptoms included fever, night sweats, weight loss, and non-breast skin lesions. 2 (2%) patients were asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis [29].

In 2/3 of patients with BIA-ALCL, late seroma developed - on average 8-10 years after prosthetics. Therefore, any seroma occurring more than 1 year after prosthetic replacement that cannot be explained by infection or trauma should be considered as a possible sign of disease. In 1/3 of the patients, tumor masses were observed, which indicated a more aggressive clinical course [30].

According to other literature sources [6, 31, 32], 8–24% of patients had a palpable tumor mass, and 4–12% had lymphopathy. Less commonly (<5% of cases), the authors described local and systemic symptoms, including skin rash, fever, and capsular contracture. Most cases of BIA-ALCL were diagnosed during implant revision surgery in the presence of persistent seroma (>1 year), as well as pain, palpable breast masses, swelling or breast asymmetry [33].

B. Adrada et al. [34] reviewed 44 cases of BIA-ALCL using various imaging modalities. They reported sensitivity and specificity for detecting effusions using ultrasound in 84 and 75% of cases, respectively, computed tomography (CT) in 55 and 83%, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 82 and 33%, and positron emission tomography (PET). )/CT in 38 and 83%. Sensitivity and specificity when determining tumor mass using ultrasound (US) is 46 and 100%, CT is 50 and 100%, MRI is 82 and 33%, PET/CT is 64 and 88%. The sensitivity of mammography has been found to be low for visualizing both effusion and tumor masses and is therefore not considered an acceptable imaging modality for diagnosing BIA-ALCL. Based on these data, ultrasound is used as a screening method, while PET/CT is used after diagnosis, for examination before surgery.

The first stage of diagnosis should include ultrasound to collect periprosthetic fluid, fine-needle biopsy of tumor masses and enlarged regional lymph nodes. Involvement of the axillary (93%) lymph nodes is most often followed by enlargement of the internal mammary and supraclavicular lymph nodes, while involvement of non-regional groups of lymph nodes is very rare [35]. Fine needle aspiration is optimal for sampling periprosthetic fluid. During suction, ultrasound can be used to gently move and protect the implant. To diagnose the disease, collect as much fluid as possible (minimum 50 ml). Periprosthetic fluid from BIA-ALCL is typically more viscous than benign seroma due to its higher protein content and cellularity. Fluid samples do not require storage in any specialized media and should be delivered to the laboratory within 48 hours. Although cells can lyse if left for an extended period, diagnostic protein markers in tumor cells are not destroyed, making diagnosis possible from fixed cells blocks years later [6]. The assessment of fine needle aspiration is difficult after a series of previous punctures, since the titer of tumor cells in the puncture may be artificially reduced. The presence of a tumor mass requires a biopsy. Specimens should be sent for morphological cytological examination using cytometry and IHC to quantify the T cells in the specimen and determine CD30 expression. CD30 IHC testing is a fundamental part of diagnostic tests, but is not pathognomonic in itself because CD30 expression is nonspecific. The CD30 antigen can be expressed on benign inflammatory cells. Rare CD30± lymphocytes with normal morphology are considered normal and do not require further investigation [13, 36].

Once a diagnosis of BIA-ALCL has been made, the physician is strongly recommended to conduct a consultation with the individual patient to determine treatment tactics. In patients with aggressive local invasion or lymph node metastasis, a bone marrow biopsy is recommended to exclude the possibility of systemic ALCL. All patients with confirmed BIA-ALCL should undergo preoperative PET/CT scanning, which is optimal for visualizing associated capsular masses, chest wall invasion, regional lymphadenopathy, and/or metastasis to distant organs. The resection strategy and timing of the operation will depend on the data obtained [10].

Treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Treatment of diffuse lymphoma is determined based on the following data:

- Risks of relapse according to IPI.

- Patient's age.

- His condition (whether the patient can tolerate high-dose chemotherapy).

The main treatments for large cell lymphoma are chemotherapy and, in some cases, radiation. Before starting therapy for fertile patients, the issue of cryopreservation of gametes (sex cells) is discussed, since treatment can cause infertility.

The main criterion for selecting therapy is the international prognostic index IPI, which includes the following aspects:

- Age. Under 60 years old - 0 points, over - 1 point.

- The patient's condition according to ECOG (patient activity and ability to self-care). 1-2 points on ECOG is 0 on IPI, and 3-4 points on ECOG is 1 point on IPI.

- LDH level. Normal - 0 points on IPI, elevated - 1 point.

- Lymphoma stage. 1-2 - 0 points, 3-4 - 1 point.

- The presence of more than 1 extranodal lesion. No - 0, yes - 1.

The IPI interpretation is as follows:

- 0-1 point - low-risk lymphoma.

- 2 points - intermediate-low risk lymphoma.

- 3 points - intermediate-high risk lymphoma.

- 4-5 points - high-risk lymphoma.

Patients from the low and intermediate-low risk group begin their treatment with 6 cycles of immunochemotherapy according to the R-CHOP-21 protocol. This regimen, in addition to cytostatics, involves the use of the immunotherapeutic drug rituximab. This scheme allows achieving five-year survival in 80% of patients. For patients with stage 3-4 disease, treatment is supplemented with radiation therapy to areas of massive and extranodal tumor lesions.

Treatment of patients from intermediate-high and high risk groups is selected individually, taking into account the patient's age and ECOG status. Young patients in good physical condition are prescribed more aggressive treatment regimens, involving high-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSC). At high risks of damage to the nervous system, several cycles of intrathecal chemotherapy are performed, when drugs are injected into the spinal canal. For elderly and weak patients, more gentle regimens are selected. The effectiveness of treatment is assessed in the middle of chemotherapy cycles and after their completion.

Current state of the problem

In August 2012, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), the Plastic Surgery Foundation (PSF), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) signed an agreement on joint research and development aimed at developing an infrastructure in which all BIA-ALCL cases would be centrally collected. The result of this joint work was the Patient Registry and Outcomes For breast Implants and anaplastic large cell Lymphoma etiology and Epidemiology - PROFILE.

In 2021, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) developed guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of BIA-ALCL [5, 6]. The NCCN guidelines for BIA-ALCL have subsequently been recognized by the FDA as well as national plastic surgery societies.

The incidence of BIA-ALCL has been estimated by various authors to range from 0.1 to 0.3 per 100,000 women with breast implants per year. However, 1 in 500,000 women with textured breast implants are at risk of developing disease 1 year after surgery [7].

Recent studies in Australia and New Zealand have found a sharp increase in the incidence of BIA-ALCL. A total of 56 cases of BIA-ALCL have been confirmed by 2021, with a further 26 new cases diagnosed between January 2021 and April 2021. The incidence was subsequently revised from 1 in 300,000 to 1 in 1000–10,000 women with implants1.

In January 2021, there were 414 reported cases of BIA-ALCL, including 9 deaths2. By February 2021, 518 patients with BIA-ALCL had been reported in 25 countries, including 194 in the United States3. According to data from April 2021, the number of patients worldwide has increased to 570, including 16 deaths4 [8].

As of December 1, 2021, the PROFILE registry included information on more than 250 patients with BIA-ALCL, and ASPS has tracked a total of more than 573 cases, including 33 deaths5 [9].

The latest data on the number of diagnosed cases is currently available on the ASPS website. As of September 3, 2021, 779 patients have been registered worldwide4.

An analysis of the occurrence of BIA-ALCL by G. Brody et al. [10], revealed significant variability in incidence worldwide, with the lowest relative incidence in the eurozone, China and Brazil. Currently, the highest reported incidence is in Australia and New Zealand (1/2832 depending on implant type) [10]. In Scandinavian countries, until recently, there have been virtually no reported cases of BIA-ALCL. Interestingly, according to manufacturers, 70-80% of implants sold in Europe are textured. Therefore, it can be assumed that, as with most tumor diseases, genetic predisposition and ethnicity in BIA-ALCL may play an important role [11].

According to a review of the world literature, the highest incidence is found in countries that have national registries of patients with BIA-ALCL, such as the USA, Australia, France, Italy and the UK. Apparently, this is mainly due to the fact that there is a standardized collection of data on all implants, as well as cases of their removal or replacement. On the other hand, the presence of registers indirectly indicates a high level of awareness of the medical community of these countries about the problem of BIA-ALCL. There may still be no real understanding of the prevalence of BIA-ALCL among women with breast implants.

Following US FDA guidelines, in 2011 implant manufacturers added a warning about the risk of BIA-ALCL to breast implant package inserts. All patients scheduled for breast replacement are required to sign an informed voluntary consent, which has three main goals: 1) informing patients about the existence of this rare disease; 2) explaining to the patient common symptoms, such as the appearance of tumor masses in the mammary glands and the occurrence of periprosthetic effusion; 3) a strong recommendation for patients to urgently consult a doctor if these symptoms appear [12].

Relapses of large cell lymphoma

When treating diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, long-term remission can be achieved in 70-80% of cases, but a number of patients experience relapse. Treatment of relapses is carried out according to the following scheme:

- Second line chemotherapy. It should suppress tumor growth while not harming hematopoietic stem cells.

- GSK collection.

- High-dose chemotherapy. High doses of cytostatics are used, which destroy the most resistant tumor cells, but they also destroy hematopoiesis, so the next stage is carried out to restore it.

- Transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells, which is designed to restore hematopoiesis.

In patients from high-risk groups who have already undergone autologous transplantation and have received a relapse of diffuse lymphoma, allogeneic transplantation is performed, i.e., donor stem cells are used. In these cases there is also a chance of complete remission, but they do not exceed 50%.

Complications of diffuse large B cell lymphoma

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy for diffuse large cell lymphoma have a detrimental effect not only on the malignant tumor, but also on all rapidly dividing cells. These are hematopoietic cells, epithelium of the skin and mucous membranes, etc. Therefore, in the process of treatment and recovery, much attention is paid to the prevention of complications. First of all, it is the fight against infections (bacterial, viral, fungal), disorders of the blood clotting system and the functioning of the digestive tract.

In addition, in the long term there is a risk of developing the following complications:

- The occurrence of other malignant tumors: lung cancer, breast cancer, stomach cancer, as well as leukemia and other types of lymphomas. The greatest risks are observed in the first decades after cessation of treatment.

- Cardiovascular complications: disruption of myocardial function, rapid atherosclerosis of blood vessels, damage to heart valves, etc.

- Lung damage: pulmonitis, pneumosclerosis and pneumofibrosis.

- Complications from the endocrine system: hypothyroidism, infertility, impaired spermatogenesis.

Risk factors for developing BIA-ALCL

BIA-ALCL can develop if your breast implants are filled with silicone or saline. This occurs more often in those who have breast implants with a rough rather than smooth surface, but the risk of developing BIA-ALCL is still low. Information about whether the implant surface is rough or smooth can be found using the breast implant ID card. It should list the implant manufacturer's website where you can find more information. You can also call your doctor's office.

to come back to the beginning

Prognosis and prevention of large cell lymphoma

The prognosis for diffuse large B cell lymphoma depends on the IPI score. The higher the score, the worse the prognosis. For patients with a score of 4-5 (high risk), the five-year survival rate ranges from 31%. At low risks, the five-year survival rate is about 91%.

As for specific prevention, it does not exist today, and all recommendations for minimizing the risk of the disease boil down to maintaining a healthy lifestyle and proper nutrition.

Book a consultation 24 hours a day

+7+7+78

Etiology of the disease

In light of recent research, it is suggested that the risk of BIA-ALCL is most likely directly related to the surface texture of the breast implant and is highest in genetically predisposed women [12]. Textured implants are susceptible to the formation of biofilms on their surface [11], which are communities of bacteria that form at phase interfaces, such as solid/liquid. Biofilm bacteria are remarkable in that they are surrounded by a mucus-polymer matrix of the extracellular substances they produce and are extremely resistant to ultraviolet radiation, dehydration and viruses, antibiotics and immune defense factors. M. Kadin et al. [13] hypothesized that BIA-ALCL is associated with chronic bacterial stimulation of Th1/Th17 antigen-driven memory T cells in periprosthetic capsule tissues and the resulting sustained proliferation of T cells with subsequent genetic events in the pathogenesis of BIA-ALCL [14] . H. Hu et al. [15] compared implant capsules from patients with BIA-ALCL and capsular contracture, finding a higher bacterial load and significantly different microbiome in BIA-ALCL samples. The authors identified a large number of bacteria Ralstonia pickettii

(a common gram-negative contaminant in drinking water), which may play an important role in the etiology of the disease, which remains to be determined.

Initial insight into the pathogenesis and molecular drivers of BIA-ALCL was gained through flow immunohistochemical (IHC) cytometry and functional experiments in characterizing the immunophenotypes of cell lines derived from patient tumors. BIA-ALCL cells showed positive staining for CD30 (a cell membrane protein), which, in the presence of anaplastic cytomorphology and corresponding clinical presentation, should be considered a hallmark of BIA-ALCL [16, 17]. Normally, the pool of CD30+ T cells ranges from 0.1 to 5% of all circulating T cells, and during inflammatory conditions in the body their concentration can increase significantly. Increased expression of CD30 can be induced on both T cells and B cells as a result of viral infection. It has been described that CD30± lymphocytes are able to temporarily increase from a background level of 0.1 to 95% [18]. Other T cell antigens expressed on malignant cells are CD3, CD4/8, CD5 and CD7 [19]. In most cases, BIA-ALCL tumor cells stain positive for multiple myeloma 1 (MUM1) (interferon regulatory factor 4) during IHC examination [20]. Genomic characterization of BIA-ALCL shows similar molecular abnormalities to ALK-negative systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (sALCL), including JAK/STAT activation and MYC/TP53 dysregulation, but clinically the disease is much less aggressive [20]. Other studies have also noted the occurrence of BIA-ALCL in women with acquired germline JAK/STAT mutations [21] and, in addition, the association of the disease with Li-Fraumeni syndrome, which occurs in the presence of a mutation in the p53 oncogene [22, 23]. In such cases, breast reconstruction using textured breast implants in women after mastectomy for breast cancer is completely inappropriate.